A World Reenchanted; or, The Second Ark of De-Extinction

Should mammoths walk again?

Part I - O brave new world

Perhaps magic was once a mighty force in the world, but no longer. What little remains is no more than the wisp of smoke that lingers in the air after a great fire has burned out, and even that is fading.

Maester Luwin

The world once was many. In Homer and Hesiod, gods roam the earth and the seas, entering into and blowing off human affairs as they please. Their offspring rule kingdoms and wage war, offering filial prayers in hope of oft-honoured intervention. It was the done thing, among mortals, to make specific, costly sacrifices to mimic these mythic supplications.

For Plato, our waking life was a constant struggle to adhere more closely to the ultimate reality of the Forms, whose world patterned our own and gave shape to perfection. Value came from the Forms, taking hold in those acts which brought our souls, embodied in imperfect Matter, into closer union with them.

Augustine wedded these ideas to Christianity, and for nearly a millennium, this was the dominant understanding of the way things really were. The resurgence of Aristotelian notions of substance chipped away at this order, but its damage was muffled by the other commitments of the Christian outlook.

Today, the world is one. The project of the Enlightenment has snuffed out the heavens and hells, unleashing in their wake the new wonder of scientific precision. There is a superficial unity to all things in the new, all-encompassing Matter, which itself confers no value. It is for us to impose where once we were imposed upon.

As Weber said in 1918, “This means that the world is disenchanted.”

Those who believe objective values exist are clinging to a relic of the earlier age, akin to brothers of the Night’s Watch sent to man the Wall. Thousands of years old, its purpose is obscure and its source unknown, yet it structures the lives of those sworn to it (some voluntarily, most against their will).

We do not look at trees either as Dryads or as beautiful objects while we cut them into beams: the first man who did so may have felt the price keenly, and the bleeding trees in Virgil and Spenser may be far-off echoes of that primeval sense of impiety... To many, no doubt, this process is simply the gradual discovery that the real world is different from what we expected, and the old opposition to Galileo or to ‘body-snatchers’ is simply obscurantism. But that is not the whole story.

C.S. Lewis

Our unified world may come asunder once more.

Quantum mechanics, indecipherable to the layman, gives pause to the march of the cult of reason. Its members are fragmented, forced by the fundamentality of the matter to take a side, knowing themselves beholden to results in a field they cannot hope to influence.

Where once it seemed many worlds were circling a single line, it could now be the case that the line is constantly fragmenting, with one world accompanying each split. The gods could intervene in our affairs; quantum branches cannot. Yet how strange it is to conceive of oneself as an insect in an anthill of selves, multiplying endlessly.

Now too, the cult of reason works new minds into existence, hoping as we are to two-dimensional beings, so they will be to our three. Still we believe we will be able to condition them to our taste.

And as silicon is impregnated, so too is the world with its children long lost. The wooly mammoth, dead these ten thousand years, may soon walk again on our account. The Tasmanian tiger, dire wolf, and aurochs could accompany it, exiting their graves across three continents.

Quietly, beyond the ears of most, magic is returning to the world.

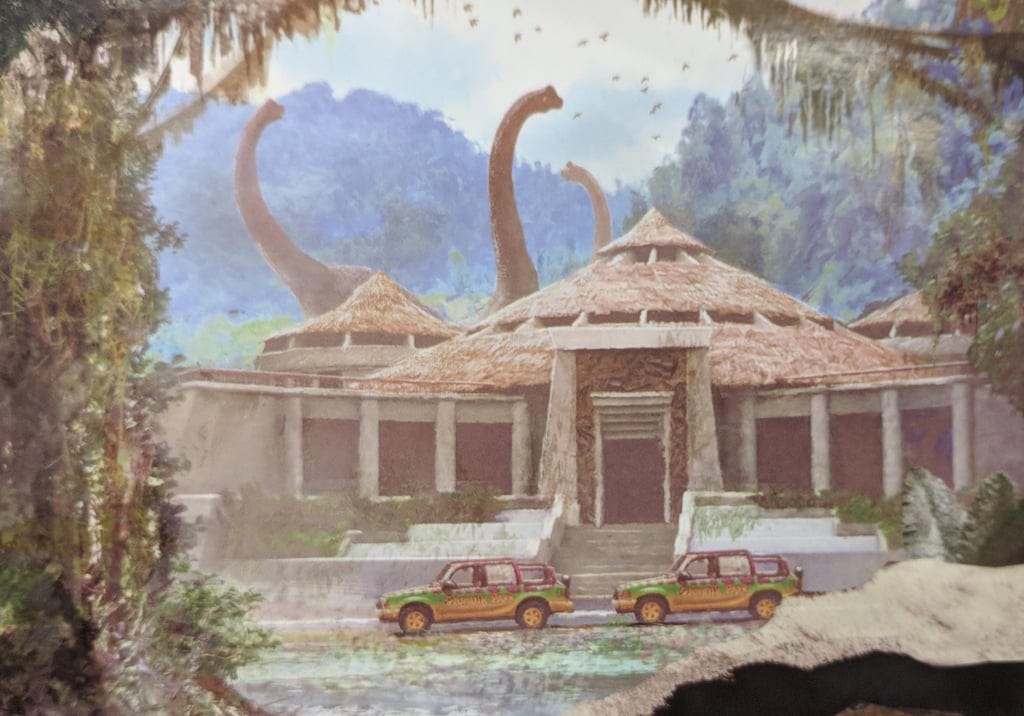

God creates dinosaurs. God destroys dinosaurs. God creates man. Man destroys God. Man creates dinosaurs.

Dr. Ian Malcolm

But it is a new magic. We are the witches and wizards; the Dr. Baxters and Frankensteins. We are the gods.

Today’s inventions most resemble the harnessing of electricity, reaching deeper and deeper into the truths of the universe until we too could conjure lightning like the thundering cloud. Agriculture, railroads, and the internet transformed life, but they did not confer upon us the ability to create it.

During the Enlightenment, figures such as Newton and Boyle uncovered fruit not only in physics, maths, and chemistry, but also in their pursuit of alchemy. They sought the philosopher’s stone, which promised to change the lesser metals for gold, and to unveil the fundamental unity of all things. In their quest, they inadvertently developed the principles of the laboratory and laid the basis for drugmaking. The byproducts were worth the failure.

Our modern endeavours have unfolded in much the same way. Semiconductors were made possible by the quantum research programme; machine learning transformed financial trading, medical imaging, recommendations, and games like Chess and Go—long before complex artificial intelligence seemed possible.

Unlike those paths past trodden, we have come upon the philosopher’s stone. The belief which undergirded the Enlightenment, that human rationality, applied with sufficient skill and focus, could lay bare the truth of the world, grows outdated. The new rationality of the machine is outpacing any attempt to understand its inner workings.

The question, as the new century truly begins, has become: were the byproducts worth the success?

Part II - Let me not dwell in this bare island by your spell

And from all that lives, from all flesh, two of each thing you shall bring to the ark to keep alive with you, male and female they shall be. From the fowl of each kind and from the cattle of each kind and from all that crawls on the earth of each kind, two of each thing shall come to you to be kept alive.

God

How are we to steward our creations? This is a pressing matter for those working on artificial intelligence, but so too for those working to bring back species from the dead.

Is de-extinction an act of preservation? Can it fulfill the command given to Noah, that order to steward the creatures of creation, which for many generations we have transgressed upon? In our best estimates, at least eight hundred species are lost every year, over one thousand times the natural rate.1 Should we bring them back?

We know there would be something uniquely wrong about human extinction, above and beyond the potential welfare of all those possible people who would never come to live. It would be the termination of a way of life that so many of us throughout time have invested in proliferating and participating within.2 The end of the human project.

In this way, we can all see ourselves in the carpenters working away at the cathedral they will not live to see finished. Yes, we want our wages and our feasts, but the knowledge that it is all for something means much to us too. And that something is not easy to articulate, and we may voice its features in as many ways as there are people, but it is real. The future gives the present meaning, and it is because we can picture humanity carrying on through it.

Were extinction to come, in a violent cleaning of the slate, and future life of an alien nature were to recover our blood, this would not be an inherently celebratory moment.

These aliens could be as Vonnegut’s Tralfamadorians, reviving humanity just to enclose it in an exhibit for their observation. This would be no revival at all, merely a sad reconstitution of the particles homo sapiens, divorced from the story they once had a leading role in.

Since we would not will our own kind brought back to sit pretty in a doll house for the curiosity and amusement of others, we must be careful bringing about such a fate for other animal races.

If we are to resurrect mammoths, dodos, and passenger pigeons, we cannot call it a continuation of their prior way of life if they are made to grow up and die in zoos by another name. The hard work of identifying compatible environments they will not overwhelm must be done if they are to live in accord with their nature.

This is an account of how to not wrong these creatures, but it says little about whether we have positive reasons to revive in the first place. Even if it’s not wrong, should we do it?

Do animals view themselves as part of a larger enterprise, and if not, how would we benefit them by extending it? A bee might be able to understand itself as a part of its colony, but not as a member of bee-kind. Let’s say we then destroyed bee-kind. Its desires are not then served by bringing back the bees, instead that specific colony would need to somehow be revived.

Humans helped wipe mammoths out, but not any of us. There are no plausible living inheritors of mammoth claims to restitution, and as with the bees, it’s not clear that the form of that restitution would be restoring the species. Perhaps their desires were more in line with preserving their habitat, or wiping out their enemy sabre-toothed tigers.

Maybe they could aid against climate change by transforming parts of the Arctic back into grasslands. Maybe they could improve our biodiversity metrics. Maybe the process would yield more research externalities. Or, maybe it would be enough for them to stand as testaments to our powers.

All of these points transform these animals into tools. They do not stand as reasons to do anything for their sake.

Colossal, ‘the world’s first and only de-extinction company’, lists all of those as reasons it plans to bring back the wooly mammoth… except the last one, which would be most honest.

But this is what we do—we tell ourselves nice stories because it is often the only way to justify the things that we do. We’d rather play God than stop being the devil.

o3 handles the conversion from E/MSY to species/year.

For clear-eyed writing on this idea: Owen Clifton, ‘Does the value of rational activity explain the badness of human extinction?’ and Samuel Scheffler, Why Worry About Future Generations?