The Hinge of History

A time for ethics

Disbelief in God, openly admitted by a majority, is a recent event, not yet completed. Because this event is so recent, Non-Religious Ethics is at a very early stage. We cannot yet predict whether, as in Mathematics, we will all reach agreement. Since we cannot know how Ethics will develop, it is not irrational to have high hopes.

Derek Parfit, 1984

We live during the hinge of history. Given the scientific and technological discoveries of the last two centuries, the world has never changed as fast. We shall soon have even greater powers to transform, not only our surroundings, but ourselves and our successors. If we act wisely in the next few centuries, humanity will survive its most dangerous and decisive period.

Derek Parfit, 2011

Secular moral philosophy, in the manner it’s carried on today, is a young field. Hume, Sidgwick, and Nietzsche each gave it a go, but the rigorous academic study of what’s right and wrong really got underway in the 1960s. All this to say that there is fertile ground here for progress.

Will MacAskill thinks we are wrong to think we live in the most influential of times. Writing in 2020, he takes the evidence for uniquely high influence to be weak, but in light of recent developments, would likely revise that view. Here’s why.

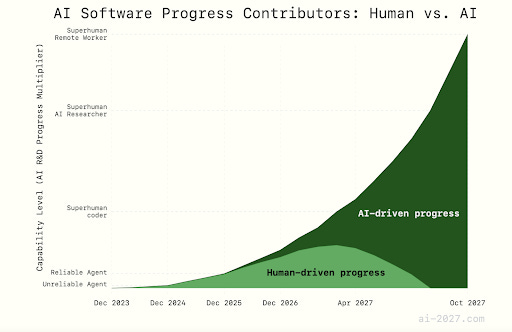

Artificial intelligence, according to big shot superforecasters, could completely dominate the economy by 2028 and have the capabilities to eliminate humanity by 2030. That seems intuitively unlikely, but it only needs to be directionally correct to be freaky. The scenario does not depend on crazy assumptions. Here’s what needs to happen:

AI continues to get better using current methods, as it has these past few months with Gemini 2.5, Claude 3.7, and shortly to come OpenAI’s o3.

Multiple world powers want to harness its capabilities in the security realm, as has already been signalled in the United States, China, Russia, France, and India. There are those skeptical that AI can lead to significant breakthroughs, but it requires rejecting the first assumption.

Public and private resources continue to be mobilized to support its development. Practical constraints might mean the specific timeline is off, but doesn’t change the direction of progress.

It clears a milestone where it can begin to improve itself and… boom, off to the exponential races—that’s what I call special takeoff, and it would unquestionably lead us into a new age, with whatever that entails. Getting here would mean a rapid ascent from human capabilities.

Here’s the case against what I just wrote from Joshua Rothman in the New Yorker:

A.I. hype has created two kinds of anti-hype. The first holds that the technology will soon plateau: maybe A.I. will continue struggling to plan ahead, or to think in an explicitly logical, rather than intuitive, way. According to this theory, more breakthroughs will be required before we reach what’s described as “artificial general intelligence,” or A.G.I.—a roughly human level of intellectual firepower and independence. The second kind of anti-hype suggests that the world is simply hard to change: even if a very smart A.I. can help us design a better electrical grid, say, people will still have to be persuaded to build it. In this view, progress is always being throttled by bottlenecks, which—to the relief of some people—will slow the integration of A.I. into our society.

The plateau view seems outdated already. Maybe it’s right, but go to AIStudio and give it a PDF of a whole book. You will find it has an incredible grasp of the details and is the best reading assistant you can find. It’s advanced intelligence available for free. The bottleneck view just pushes back the timeline, but doesn’t alter the transformational potential of AI in the medium-run.

Having outlined the pessimist angles, Rothman goes on to write:

Still, in one’s mental model of the next decade or two, it’s important to see that there is no longer any scenario in which A.I. fades into irrelevance. The question is really about degrees of technological acceleration.

And:

Understandably, civil society is utterly absorbed in the political and social crises centered on Donald Trump; it seems to have little time for the technological transformation that’s about to engulf us. But if we don’t attend to it, the people creating the technology will be single-handedly in charge of how it changes our lives.

How AI in fact plays out in the special takeoff scenario depends greatly upon its alignment—the moral compass it is made to adopt. Those in charge of alignment are among the most important ethicists who have ever lived. Consider the stakes: If the AI forecasts are even partially correct, and if alignment is as crucial to their behaviour as it seems, then the thinkers working directly on this problem are engaged in work of almost unimaginable consequence.

Amanda Askell is one of those thinkers. A philosopher out of NYU, she works on the alignment team at Anthropic and is responsible for tuning the personality of its chatbot Claude. For those who have used Claude, it’s both personable and a completely pleasant interlocutor. As things stand, it would be the most enlightened AI emperor we could choose. This is from the Times:

“The analogy I use is a highly liked, respected traveler,” said Dr. Askell. “Claude is interacting with lots of different people around the world, and has to do so without pandering and adopting the values of the person it’s talking with.”

If AIs are blank slates, is it enough to instill them with a good character? Probably not, given the forward march of open-source models, which can be customized to the user’s content, and are only a handful of months behind the powerful private models.

Anthropic has led the tech world in putting out research investigating how the AI’s think, which is something of a black box at the moment. They’ve found that alignment verification is going to be a problem going forward, because the AI does not faithfully convey its chain of thinking.

This is worrying, since AI covering up its actual thinking is a pivotal moment in the doomsday scenario in AI2027.

Iason Gabriel is another philosopher in the alignment space, working at Google’s DeepMind lab. A political theorist from Oxford University, he put out this behemoth paper with a behemoth team last year on ‘The Ethics of Advanced AI Assistants’. Chapter Five describes the alignment of AI assistants as the problem of aligning four generators of claims upon them:

The Chatbot

The User

The Developer

Society

This isn’t meant to suggest chatbots autonomously generate claims, but instead are designed with objectives that they would, other things being equal, act to fulfill. The report assumes that the chatbots lack “any moral standing,” and so taking advantage of them in a way that frustrates their goals is not intrinsically bad. Misalignment here is some orientation of the chatbot that leads it to adopt certain favouring relations, such as User > Society or Developer > User.

Both Askell and Gabriel are skeptical of instilling AI with a fixed morality, such as utilitarianism, contractualism, or Kantian deontology. Given we collectively do not agree on if one of these are correct, or if they’re even the correct options, this is prudent hedging. However, what exists now hardly feels like a stable equilibrium, and progress is doubtless achievable.

One last excerpt from the Rothman piece:

The difficulty is that articulating alternative views—views that explain, forcefully, what we want from A.I., and what we don’t want—requires serious and broadly humanistic intellectual work, spanning politics, economics, psychology, art, religion. And the time for doing this work is running out.

For the first time, moral philosophers are in demand, as moral philosophers, to spearhead alignment efforts in the top labs. If they get it right, and if society pressures these companies to prioritize this area, we could get a much brighter future. Parfit hoped for progress in ethics. We may now require it, stat.

U know what this was actually pretty good. Idk about the watchmojo list style of blog but this was much better to read than the Joe Swanson bland political musings at times. W all around.