The Cincinnatus Problem

Presidential power begets presidential power

I. Leaders Are Getting Stronger

The American presidency has become unambiguously more powerful since its inception. This largely stems from the expansion of the administrative state, which oversees a great number of regulatory agencies and social programs, and the ceding of foreign policymaking by the legislative branch to the executive.

Early presidencies were not that strong, exercising most of their authority in international disputes and treaties. Jackson became notably more involved, issuing more vetoes than all of his predecessors combined and threatening the use of military force domestically to keep South Carolina in line.

Power receded from there until the secession of the Confederacy, when Lincoln suspended the right not to be arbitrarily detained, instated a draft, and assumed total command over the war effort.

When the Civil War ended, many of the emergency powers that were granted to Lincoln were clawed back by Congress, leading to a weak executive throughout the 1870s, 80s, and 90s. Teddy Roosevelt began to reverse that trend, adopting a theory of power “limited only by specific restrictions and prohibitions appearing in the Constitution or imposed by Congress under its constitutional powers.”1

Wilson took this idea to the extreme, creating the modern administrative state. During the First World War, he exerted unprecedented control over the domestic economy, and moved to enact the Espionage and Sedition Acts, which drastically curtailed free expression. When the time came to make peace, he attempted to sideline Congress entirely—a strategic misstep that set back the cause of presidential power by a few decades.

Nevertheless, Franklin Roosevelt admired Wilson and his vision of expanded government power. Given the legislature’s reluctance to achieve that vision on its own, he took it upon himself to spearhead the most aggressive domestic policy agenda in American history from the top down. From Wilson’s peacetime high of 391,000 executive branch civilian employees in 1916, Roosevelt oversaw a near threefold increase to 1,081,000 in 1941 (still two months before the attack on Pearl Harbor).

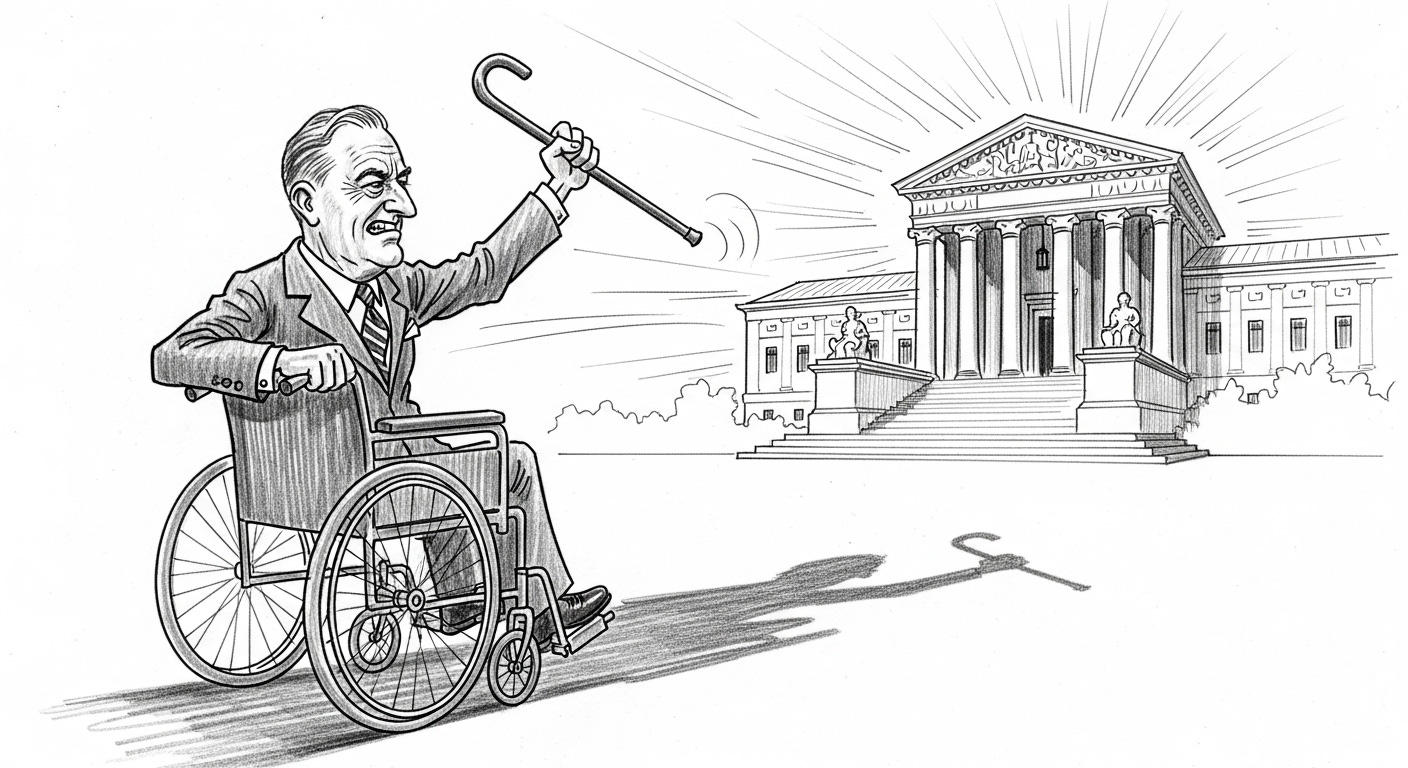

Roosevelt sought not only to bend the legislative branch to his will, but also the judicial. When the Supreme Court ruled against parts of the second New Deal, he threatened to pack it with sycophants that would bulldoze it through. Like Wilson, his ego had gotten the best of him, and this proved to be the greatest strategic misstep of his presidency. By mid-1937, the tremendous momentum of his policy programme had vanished and he transitioned into managing the growing crises in Europe and Asia.

The Second World War expanded the executive in new ways, with Roosevelt ordering Japanese Americans interned, instituting price controls, taking command of private industry, and developing the Manhattan Project in secret. In total, he issued 3,726 executive orders, still by far the most ever issued.

Truman kept up the momentum, establishing the Central Intelligence Agency, entering the Korean War without a declaration by the legislature, and attempting to seize private steel mills in order to prevent a major strike. His successor, Eisenhower, mobilized federal forces to integrate schools, formalized “executive privilege” to shield the presidency from legal enquiries, and loosed the CIA on Iran, Guatemala, Cuba, and Vietnam.

Lyndon Johnson pushed executive power to its then-limit. The former continued his predecessor’s use of federal forces for domestic purposes, deployed the FBI for political intelligence gathering, and oversaw an administrative state that had nearly doubled in size from 1941. He also waged an undeclared war in Vietnam, which was continued by Nixon for more than four years.

Tricky Dick thought he could go yet further. Abroad, he secretly bombed Cambodia for fourteen months, then proceeded to invade both there and Laos. At home, he ignored the legislature’s budget decisions, applied executive privilege to all communications, and attempted to weaponize the administrative state to harm his political opponents.

Congress reclaimed a place for itself after these humiliations, but it wasn’t long lived. Reagan secretly sold arms to Iran in order to finance Nicaraguan rebels, promised to only enforce laws he deemed to be constitutional, and continued the trend of unauthorized adventures abroad—a torch which Clinton would carry forward proudly.

Bush Jr. presided over the 9/11 attacks, which catalyzed Congress to essentially surrender its remaining illusions of foreign policy powers to the executive branch. The state’s domestic surveillance efforts were simultaneously supercharged in the name of counter-terrorism. Obama maintained this apparatus and waded into immigration-policy-by-executive-order, which Trump would continue.

The first Trump administration invoked a domestic national emergency to redirect funding to immigration efforts on the southern border, an omen of things to come. Though efforts to spin up an election victory were roundly rejected by the judiciary, they happened not to be an instance of overreach sticking in the public conscience. After four years of Biden mostly being defeated by the Supreme Court, Trump stormed back.

Seven domestic national emergencies have been declared in the first six months of the second Trump administration, more than the sum of previous such orders (excluding his own) across American history.2 The presidency has granted itself new powers to fast-track projects, control migration, and drastically restrict trade. It has never been stronger in peacetime.

Just as I was putting this article together, the Supreme Court barred lower-court judges from blocking potentially illegal government actions. This could allow an executive order dismantling birthright citizenship to temporarily stand.

II. Leaders Shouldn’t Do Too Much

Presidents shouldn’t do too much domestically, because baseline governance is hard to improve upon and easy to worsen.

Societies are extremely complex orders, with little bits of unique information stored in millions of citizens. Left with minimal governance, including the rule of law, contract enforcement, and the provision of certain core public goods, they tend to wield their information well and flourish in the long-run. Countries that check these boxes regularly achieve 2% annual growth and avoid famine.

Improving upon the complex order through top-down action is hard. No leader’s information is going to be better than any individual’s nuanced information about their own life. There are gains to be had when private coordination is breaking down, but executives, as a rule, over index on the public’s perception of breakdowns, rather than the ground truth. One common failure is attempting to ‘create’ jobs:

Disrupting society in a bad way through similar action is very easy. 2000, Zimbabwe; land reforms redistribute farms to non-farmers—agriculture collapses and the worst hyperinflation in history follows. 2014, Venezuela; price controls are implemented and oil prices collapse—the economy grinds to a halt and the government’s income dries up, destroying the state.

In the United States, Nixon attempted wage controls in 1971, only to induce shortages, rationing, and newfangled black markets. That was a local maximum of presidential overreach—will we soon see its like again?

Taking all of this into consideration, we should hold a strong prior belief that activist leaders have high downside risk and low potential upside; this is a result of the asymmetry between government’s ability to do good and its ability to do bad.

Legislatures are slower to move than executives, such is the nature of deliberative bodies. Since domestic action is negative in expectation, it is better that the balance of power lean towards Congress.

III. It is Hard to Stop Leaders from Doing Too Much Once You Let Them

The presidency has had the balance of power tipped in its favour and this is a bad thing—it should be radically disempowered. Unfortunately, I want to show that this is a difficult problem. The levers of power must be wielded to cast themselves into Mt. Doom. This is much easier said than done; the history of groups using power to diminish power is anything but inspiring.

Our model here is the Cincinnatus story, about a man granted extraordinary power to address a crisis, doing just that, and giving the power right back to those who granted it to him. It is often invoked in reference to Washington, who rebuked a crown and retired from public life after two terms as president.3

There are good stories to tell from elsewhere. In Spain, after the death of Franco, King Juan Carlos I assumed power as an authoritarian and chose to support the country’s shift to democracy. When, in 1981, members of the military attempted to stage a Francoist coup and held the entire parliament hostage at gun point, he took to television to say:

The Crown, symbol of the permanence and unity of the nation, will not tolerate, in any degree whatsoever, the actions or behavior of anyone attempting, through use of force, to interrupt the democratic process of the Constitution, which the Spanish People approved by vote in referendum.

The plotters viewed themselves as deeply connected to the monarchy, as Franco had chosen the king to succeed him. So when he delivered the speech, it spelled death for any claim to legitimacy on their behalf, effectively securing Spain’s democratic transition.

Juan Carlos had a unique position as a national symbol existing outside the political system. There was an element of moral courage in identifying his personal interests with the unity of his nation, but he also was not a political creature. By all accounts he was not interested in absolute power.

This cannot be the case for insiders within the sort of institution that the American presidency has become. Neither of the two major parties has a theoretical interest or a revealed preference for de-escalating the executive branch’s power creep. Instead, they are entirely composed of political creatures that believe in leveraging power to enact their visions of the good.

We can call this the partisan ratchet. When Party A holds the presidency, it expands its power to achieve its policy goals; Party B, in opposition, decries the executive overreach as a threat to the constitutional order. Eventually Party B wins the presidency, inheriting the new powers created by Party A. Rather than relinquish them, it uses them to pursue its policy goals, because their immediate political interests are more powerful than their more abstract interests in a well-balanced system.

Given the presidency lacks incentives to bind itself, we must look elsewhere. In the narrative of presidential power, much of the expansion seemed as though it could be laid at the legislature’s feet. Could they reverse it?

Perhaps, but the system has played out such that Party A’s presidency often coincides with Party A’s Congress, giving them an immediate interest in supporting their guy. Given they might lose a midterm, isn’t it best to empower him to continue achieving their policy goals whilst the House and Senate are gridlocked?

A large share of the expansion has come during national crises, where the public demands short-term action. Executives are naturally better suited to this and elections are often right around the corner, so the popular course of action is, inevitably, empowerment.

The judiciary faces similar pressure, beholden to public opinion in more subtle ways. Appointment powers are vested in the presidency, subject to Congressional approval, meaning that the institution which wishes to be unconstrained is choosing the members of the board meant to constrain it.

IV. Okay, but What Would It Look Like if We Did It?

If, for example, elected Democrats were profoundly rattled by the excesses of the first Trump administration, they could have tried to make the case for reining in the presidency to the American people. Instead of expending political capital to pass a series of spending bills, they could have pressured Biden to support a clawback amendment to the Constitution.

There’s a chance Republicans would have leapt at the opportunity to curtail their rival. Remember that at this time, Ron DeSantis was a credible challenger to dethrone Trump within the party, and there seemed to be some taste among their electeds to move in a new direction.

The exact content of such an amendment is beyond our purview here, but it would potentially clarify the nature of the many contested presidential powers, such as the scope of executive orders, budgetary impoundment, selective enforcement, and national emergencies.

Biden’s advisors may not have liked it, but there was a shot in 2021 for him to deescalate. This would have been an act of serious moral courage that reflected a substantive commitment to cooling the national temperature, rather than merely gesturing at the goal rhetorically. Unfortunately, the tendency of our age is to go up the escalation ladder, not down.

In reality, Biden was strongly pushed to pack the Supreme Court, a move he wisely resisted. He shepherded piecemeal reforms through Congress regarding election certification and nonpartisan civil service protections, but declined to think bigger.

Today, Democrats in Congress are moving lots of bills forward that purport to limit executive power. They will almost assuredly all fail, because it is not credible to only seek to impose constraints whilst you are in opposition. If they did somehow pass, they would merely be laws, able to be repealed by future simple majorities. A true reckoning must go beyond such fragility, with the most obvious path being the Constitution itself.

In the meantime there is plenty more room to escalate.

Theodore Roosevelt, An Autobiography, p. 357

Excluded are emergencies primarily purposed at coercing foreign actors rather than achieving some domestic end.

Oddly enough, you can find it invoked too in reference to Biden, which is amusing given all of the reporting that has come out surrounding his decision to drop out.

The Biden Isildur comparison was great, as was the historical commentary. It seems that we are destined to increase admin power, but what about that clawback in the late 1800s? What about their political economy was different from ours to allow for such a thing?