"Creating Jobs" Isn't A Policy Justification

Stop the cap.

On a stop in Michigan to promote his infrastructure bill back in 2021, President Biden leaned plenty on the idea that the legislation would create two million jobs annually (for the ten years of its scope). In 2023, job creation was presented as part of the argument for the CHIPS semiconductor bill. Today, President Trump is justifying his tariffs, in part, by claiming “We will take in trillions and trillions of dollars and create jobs like we have never seen before.”

It’s a very popular justification for policy decisions, up there with growth, protection, inequality, security, and the environment. More jobs = more good. But it’s often a bad one, and when it could be a good one, it tends to get used dishonestly.

The poster child policy programme based on this line of argument is the New Deal. Give this passage from Robert Caro’s The Path to Power a read and tell yourself you can’t grasp its appeal:

Once out of school, young people found themselves looking for jobs in a world with few jobs to offer. In normal times, some would have been taken on as beginners or apprentices, earning enough to live on while they learned a trade. Now, with even skilled men pounding the pavements, who was hiring apprentices? Of the 22 million persons between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five in the United States in 1935, at least 3.3 million—and perhaps as many as 5 million—were both out of school and out of work, millions of young people drifting through their days with nothing constructive to do.

The President’s Advisory Commission on Education was to warn of a whole “lost generation of young people.”

It’s primally disturbing. Children coming of age in a world that, through no fault of theirs, offers no purpose—that, in fact, opposes them at every step of their efforts to forge ends of their own. The crucial relationship between striving and reward is broken; its pattern of sense-making which it imposes on the world gone away.

Of course action was needed. But misery alone does not make job creation the prevailing motive to act.

It is sometimes the case that structural refigurings of economic life are underway. In these periods, those shut out from employment suffer their plight on account of lacking the skills or position to participate. Changing conditions—be they technological, geographical, or institutional—prompt an adjustment period that short-term moves to prop up the old order won’t overturn.

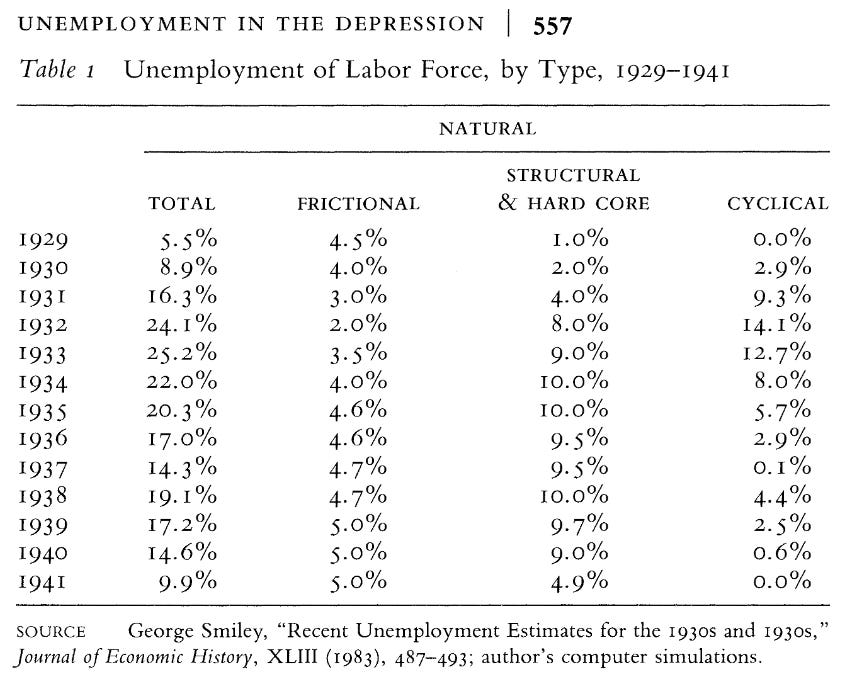

For instance, during the 1920s, mechanization was rapidly making food production more efficient and necessitating a move of labour to the urban cores. Manufacturing, transportation, chemicals, and plastics were arriving on the scene to absorb it, but it was going to take a while for the workforce to catch up. You can see these trends playing out in the two visualizations below—notice how static frictional and structural unemployment are from 1932-1940.1

Other times though—the red periods in the graph below—the problem is a dearth of demand in the economy. Businesses want to employ as they have been, workers want to labour in the same old way, but there’s not enough spending going around to pay their wages. The thinking in times like these is that government can create jobs and fix the gap.

Though it’s not charted, the Great Depression fit this description.

The infrastructure bill (Q4 2021), CHIPS (Q3 2022), and the various new tariff schemes cannot claim to be in this bucket.

Taking such measures when the blue line is beneath the red is inflationary, both for prices and wages, since the stock of willing, able workers is exhausted. Those who are left are either victims of the aforementioned structural changes, or workers in between jobs (just like how housing vacancy rates are always greater than zero, allowing people to move).

They might reallocate jobs, but there’s no creation going on here.

This piece though, is titled to suggest that employment-based justifications are never available, and the reason for that is simple: historically, when job creation has been mustered to defend a policy, the actual content of the policy has often betrayed the claim. FDR is a case in point.

Good Intentions, Muddled Results

The New Deal was made up of lots of disparate components. The Public Works Administration, Civilian Conservation Corps, and Civil Works Administration were all explicitly sold on creating new jobs and collectively employed over 8 million across the 1930s. So far, so good—that’s the idea.

Simultaneously, the Wagner Act and Fair Labor Standards Act strengthened labour unions, established minimum wages, and promised overtime pay to those working over 40 hours a week. Robert Gordon writes that this “contributed to a sharp rise in real wages” and prompted “firms to economize on the use of labor,” leading to resources being substituted away from workers. This meant more spending on equipment per worker and helped to boost productivity.2

Productivity is great, but it is great because it leads to growth (which raises living standards). Substitution away from labour causes job loss, counteracting the effects of the big ticket public employment programs.

Indeed, President Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act—“the most important and far-reaching legislation ever enacted by the American Congress”—may have increased unemployment by as much as 6%.3

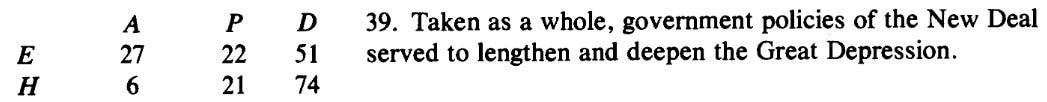

Robert Whaples surveyed economists and historians in 1995 on a number of questions in economic history, and one of them was whether the New Deal worsened the Great Depression. Contrary to a strong consensus in the historian camp, economists were split 50/50 on the matter (P indicates conditional agreement):

That’s not surprising. Robert Gordon gives a good argument that despite worsening unemployment, the policy programme as a whole boosted long-run living standards by shifting resources into capital investment, eliminating bank failures (via the FDIC), and spreading electricity across the country.4

But were they surveyed on whether the policies of the New Deal served to fix the unemployment crisis, I think the consensus would be much more in the “No” camp.

The Verdict: The job creation argument is a hollow political ritual and the rhetorical menu could do with one less option. You shouldn’t think that such programs will achieve anything good when employment is very low, and when unemployment is actually high, you shouldn’t trust politicians selling their ideas on the basis of generating new work. History suggests they have other, higher-priority aims.

This data is old, but illustrates the underlying point accurately.

Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Chapter 16.

Jensen, ‘The Causes and Cures of Unemployment in the Great Depression’, footnote 24.

Gordon, Chapter 9.

:( Im getting nuked