Why We Can't Talk To Each Other

A diagnosis of politics

Here’s how public politics is supposed to work, in a world where we reasonably cannot agree on the good.1

Alexandre lives in a constitutional democracy called Deliberatia. He’s politically engaged, going down various YouTube rabbit holes, taking some classes in philosophy, and chatting with friends at the bar downtown to learn a fair amount about the world. After thinking pretty hard about it, Alexandre adopts a worldview—libertarianism—joining a larger group of people who roughly think like him and share his values.

When Alexandre shows up to a party he’s invited to and inevitably decides to talk politics in the corner, he does not talk in the language of libertarianism (he tried that a few times and got nowhere). He has to translate to the language of shared values with the person he’s talking to.

On this occasion, the other person happens to have a Christian worldview. Trying to pitch the Christian on libertarian ideas about taxes, Alexandre talks about how important and meaningful it is to freely engage in charity and how the state renders it more difficult to demonstrate the virtue of generosity. He goes on about how concentrating political power in the hands of a few invites the temptation to grow that power and exploit it.

His tailored translations aren’t always persuasive, but they’re essential for reaching the person he’s talking to. Eventually, when the song changes and the Christian wiggles away, Alexandre is left unsure about his success, but confident he was comprehensible.

As he gets older, he decides to enter public life. He graduates from libertarian to Libertarian, running to represent his party and community in the Parliament of Deliberatia. Suddenly he isn’t talking to one or two other people, but tens of thousands, all of whom have (consciously or subconsciously) their own worldviews. Wanting to reach potential voters, he has to translate his ideas to the language of values shared by all of these worldviews—the language of public reason.

This is not a trivial translation exercise. Like anyone raised in Deliberatia, Alexandre has intuitions about what everyone takes for granted in its politics. You can’t touch the public healthcare system, the state pension, or the ballooning marble maintenance fund, for instance. But within these sacred cows are deeper values to uncover: equality, safety, care, reciprocity, tradition. So it goes with the state’s founding documents, which espouse liberty, industry, fraternity, and sobriety. He has to figure out not only what these underlying values of Deliberatia’s political culture are, but also how to conceptualize their hierarchy.

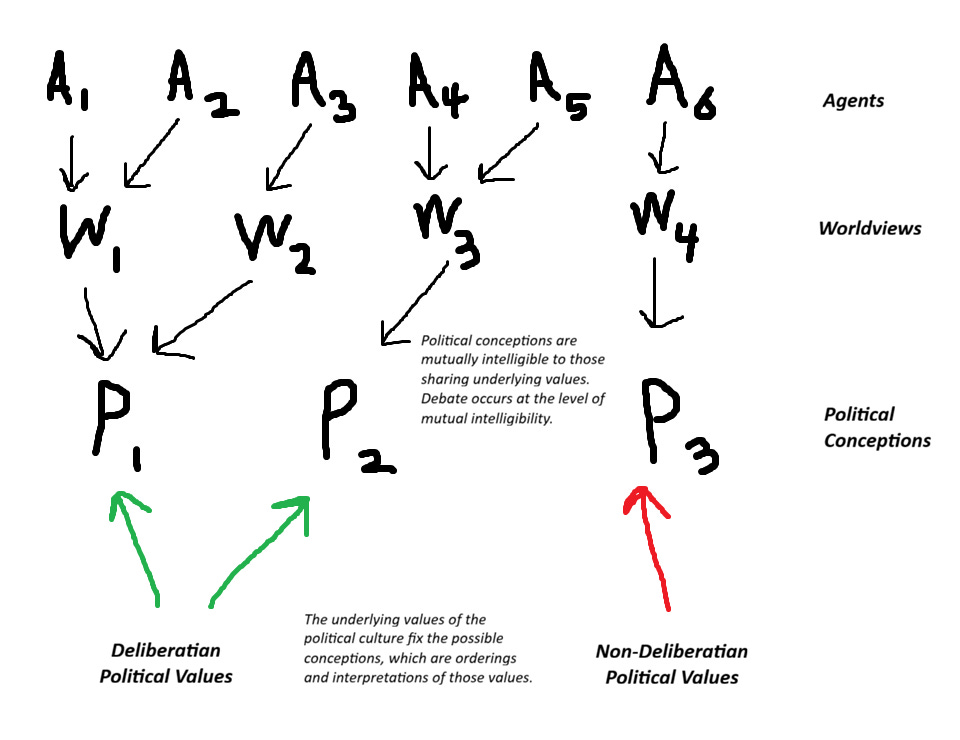

Because these values, which can be listed with widespread agreement, can be interpreted in different ways and ranked in different orders while still being upheld, the language of public reason is open to multiple reasonable political conceptions, of which Alexandre’s is but one. What makes them reasonable is their affirmation of the values of Deliberatia’s political culture.

The debate in Alexandre’s riding pits his conception, of liberty and industry’s priority, against that of the socialist, who argues for fraternity and equality. When they come to substantive policy disagreement, neither side appeals to the commitments of their personal worldviews—Alexandre doesn’t decry taxation as theft, the socialist avoids mentioning the frigidity of rugged individualism—unless they can find a way to ground it in their conceptions of Deliberatian values.

When the election comes and one of them loses, they can hold their head up high knowing they lost to a bloc of reasonable cooperators: fellow citizens with different weightings and interpretations of the same political values.

To recap the view: agents match to worldviews, which each endorse a political conception (an ordering and interpretation of political values); when a conception orders the values of the public political culture, it is reasonable and can talk, in the language of public reason, with other such conceptions; when a conception orders some other set of values, it is unreasonable, in the sense that the reasons it could offer in public reason would not be accepted by those in the political culture.

But there’s an obvious meta-implication here. This all means politics is downstream of culture, which tracks what we all recognize: successful efforts to change our culture can completely change what we accept as (and what actually is, in this view) reasonable. Altering the political values is the highest-order level of political maneuvering—it transforms public politics from the outside.2

Part of what makes certain politicians epochal, like Donald Trump, is that they operate at this higher level and deliberately affect change in the culture.3 The United States is going through an instability in its political values because he and his movement’s value commitments have been so persuasive and influential.

Lots of people who view themselves as doing politics right, by arguing within public reason, are frustrated by the centrality of the Culture War. Knowingly or not though, the culture warriors are plausibly engaged in the most important political battle of them all. If you feel like you can’t talk to them normally, that’s because they don’t want those kinds of conversations to be normal. They want people to be having a new range of conversations.4

John Rawls, ‘The Idea of Public Reason Revisited’

Thanks to Gina Schouten, who helped me grasp this point in relation to public reason.

For example, Trump did not want to hold his head high knowing he lost to reasonable cooperators, instead he sought to throw that norm into question.

I realize while writing that this is a public reason-flavored Overton Window, which itself is a super useful concept.