Against Lotteries

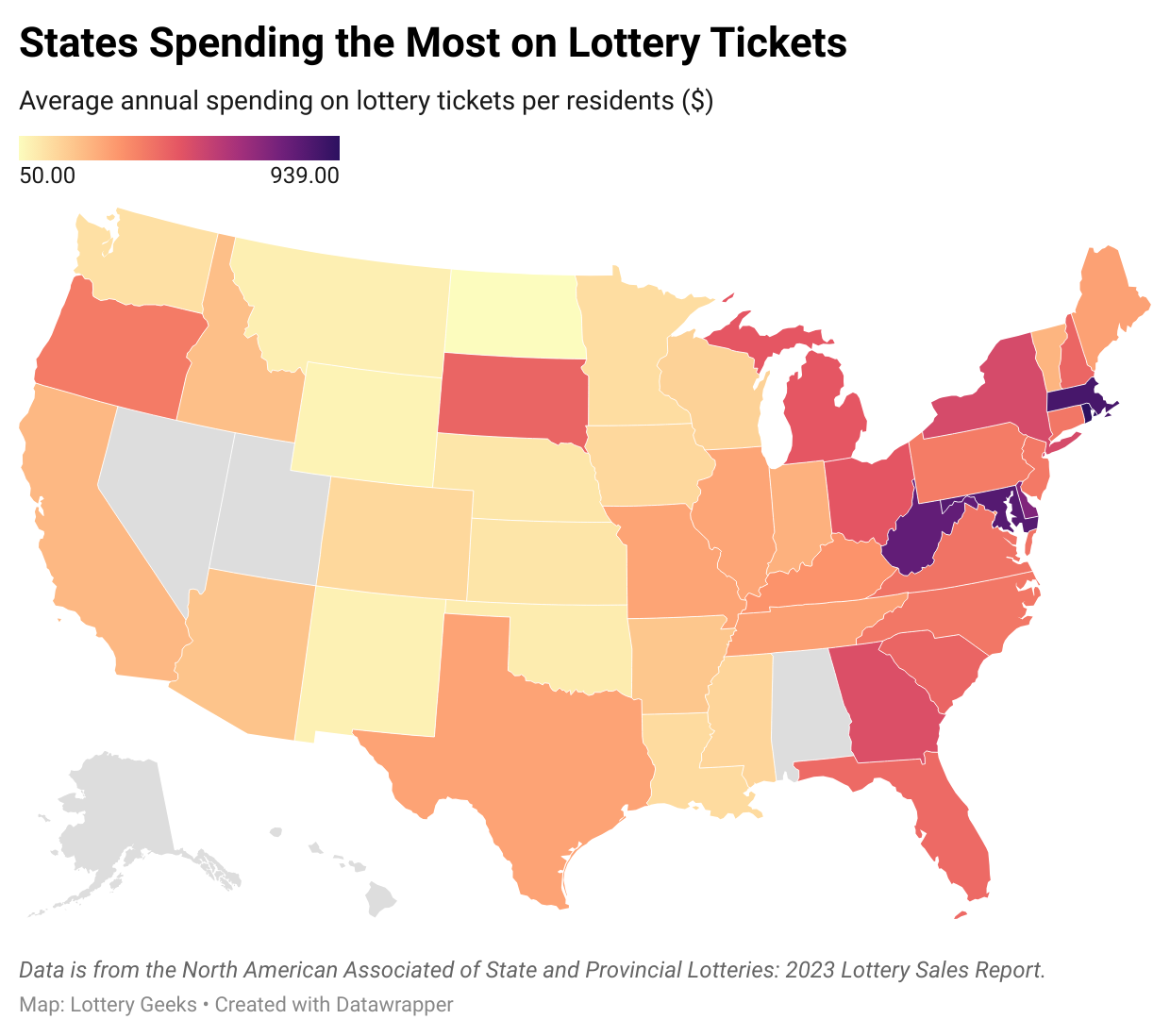

West Virginia, mountain mama

Lotteries are ubiquitous in the western world.1 You see their tickets for sale every time you go to the corner store or grab some groceries, though, judging by Substack’s demographics, you probably don’t play.

Tonda Dickerson was a single mom getting by as a Waffle House waitress who was tipped a lottery ticket in 1999.2 In normal circumstances, you’d rather have the cash—but, by some stroke of luck six nights later, that ticket won the $10 million dollar jackpot.

She got sued by her fellow waitresses. She got sued by the guy who tipped the ticket. She got held at gunpoint by her abusive ex-husband (and wound up shooting him). All for a slice of that pie. Then she got sued by the IRS.

Her experience isn’t all that out of the ordinary. I encourage you to glance at this thread of advice for lottery winners, you’ve got implorations to

Change all your phone numbers and get a PO box

Disappear for at least a month abroad

Avoid local and family attorneys like the plague

Prepare for zombie cousins emerging from the bush

Or else you will go BANKRUPT and DIE. At least that seems to be the message.3

What’s the point?

Okay, if lotteries are scary and hurt their winners, why is the state sponsoring them? The government is involved because there are a lot of people willing to donate a lot of money to them when the donation box is labelled ‘Power Ball’ or ‘Mega Millions’. Private lotteries are not really a thing, because states want to monopolize these revenues.

Looking at the United States, all of its lotteries put together raised $113 billion in 2024. That’s $337 per capita or $862 per player.

Zeroing in on the state leaders in 2023, you had Rhode Island at $939 per capita, Massachusetts at $877, and West Virginia at $812. Taking the national playing rate of 39% and applying it to these states, that’s $2,400, $2,250, and $2,000 per player, respectively.

For a number of states, lottery revenues represent a serious chunk of their discretionary budgets, on the order of 3%. In West Virginia, a true lottocracy, o3 estimates 12% of that budget is funded this way.

So there’s a big governmental stake in these continuing to operate. That explains the why, but now I want to go over the various shoulds and shouldn’ts to figure out whether this is clever fundraising or something darker.

Is this right?

We’ve established the way in which lotteries act as an important revenue source for various governments, but we’ve also read about how badly things can work out for some of the winners. Some readers’ gut reaction to such stories will be normative. They will think thoughts like ‘people shouldn’t buy lottery tickets’, while others will think that ‘people should do what they please if it’s only hurting themselves’.

Others might be a little uncomfortable with state budgets being made up of gambling revenues. They could think ‘the state has no business selling or advertising social ills for its own gain’, or that ‘the state is preying unjustly upon the poorer classes, who buy up a larger share of the tickets’.

The first group of people is doing really applied ethics, while the second group is posing important questions in political philosophy. Let’s focus on the latter.

They’re asking: when is the state justified in running lotteries?

One move we could make is to collapse this into the question of when states can justifiably levy taxes. But there is an important difference between a lottery and a tax—they’re completely voluntary. No charges are forthcoming if you fail to dutifully buy your tickets that month.

That’s going to matter as we survey the mainstay views on tax justice.

Libertarians should oppose state lotteries

Libertarians, like Robert Nozick, tend to conceive of a moral right to own property and what is made from that property. If such a view is true, then taxation by the state is a form of theft.4 Yet that is because it is compulsory—a voluntary lottery does not have this problem.

For the libertarians, the problem lies firstly in the state’s enforcement of a monopoly on the lottery, not allowing private alternatives to freely operate. It uses the threat of force to prevent a category of peaceful, voluntary transactions from taking place. This is a clearcut violation of economic liberty.

Others in this camp may object to the idea of the state operating a commercial gambling enterprise, given its mandate to serve as a keeper of peace and contracts. However, I suspect this is vulnerable to the critique that voluntary lotteries may be the least objectionable means of financing the basic operations of the state, given they involve minimal coercion.

Egalitarians should oppose state lotteries

Egalitarians, like John Rawls, view property rights as products of a political system which must, on the whole, accord with the principles of justice. This view rejects the idea that pre-tax incomes have any special normative status. For egalitarians, the fact that a lottery is voluntary has minimal bearing on whether it is just; instead, they are interested in the ability of lotteries to achieve a just distribution of resources.

Right off the bat, it is implausible to suggest that lotteries achieve more just distributions of resources. This is because lotteries are empirically regressive; that is, they disproportionately sell tickets to poorer people.

Egalitarians take issue with this because they tend to endorse something like Rawls’ Difference Principle, which holds that the economic distribution should be arranged to be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged. They would argue:

Regressive taxes raise revenue from the least advantaged

Progressive taxes could raise the same revenue from the more advantaged

Progressive taxes would not reduce the overall benefit to the least advantaged

Therefore, by running a lottery, the state fails to arrange the tax system to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged.

This argument is probably sound, with the caveat that high enough levels of progressive taxation could erode the incentives for the most advantaged to produce positive externalities for the bottom end of the economic distribution—think technological innovations and productive but risky investments. Would these effects kick in at taxation levels necessary to cover modern lottery revenues? I am skeptical, but economics has the tools to investigate.5

Here’s another objection to lotteries from the egalitarian standpoint, which appeals to an explanation of why they turn out to be regressive:

Lottery sales depend on cognitive biases; they would not occur at the same rate if people were fully rational

The least advantaged have a relatively harder time overcoming cognitive biases

The state is aware of both of these facts

Were the state to stop its sales and embrace a total ban, no serious black market would emerge for lottery sales

Thus, the state is knowingly undermining the ability of the worst-off to rationally pursue their overarching life plans by acting as the sole purveyor of lottery tickets.

Many governments finance advertising campaigns that demonstrate the third premise—these ads aren’t running in the Economist or New Yorker. The fourth is the toughest to prove, but seems plausible. In my experience, lottery purchases are often marginal, being additions tacked on to other purchases at the corner store or grocery store. Would people really substitute that spending into the casino if the lotto ended?

Utilitarians should oppose state lotteries

Utilitarians, like Bentham’s Bulldog, share the egalitarian’s interest in the outcome of taxation. They also want to know whether lotteries achieve a just distribution. However, their standard of just distribution is that which maximizes welfare.

They would first appeal to the marginal utility of money at different levels of income. Lotteries, by virtue of being regressive, raise revenue from those for whom money has a high marginal utility. Progressive taxes could raise the same revenue from those for whom money has a lower marginal utility, without reducing overall utility, so they should be preferred.

Similar to the egalitarian case, there is valuable research to be done on when taxes become progressive enough to reduce overall utility. This is slightly different from the ‘tipping point’ the egalitarian needs to figure out, since the utilitarian is concerned with the sum of everyone’s welfare rather than the welfare of the least advantaged group.

We could object that there is a lot of utility in actually playing the lottery. People are paying for the thrill of what might happen, not to maximize their wealth. That is, analyses like these make the mistake of treating gambles as investments.

Maybe so, but the objector must explain why the welfare-maximizing move by the state is to instate a monopoly which allows it to take higher profit margins on the lottery tickets than the market would otherwise bear.

Well then…

It turns out that all three of these stances lead to the conclusion that the state is acting unjustly when it operates a lottery; a rare bit of cross-theory agreement.

The state is establishing a monopoly over a gambling product to regressively raise revenue. Libertarians must take issue with the monopoly; egalitarians must take issue with the product and the regressive incidence; while utilitarians should recognize the first and third concerns as empirical failures to maximize welfare.

In light of these issues, the state should move to (1) ban all lotteries, including its own or (2) deregulate lotteries, surrendering its monopoly. Egalitarians are able to make a case for (1), and utilitarians could in theory go along with that case, but I believe in the end they would join the libertarians in endorsing (2). Even the egalitarians, owing to their commitments to basic liberties, could opt for a version of (2) that ends direct government involvement and creates a rules-based order for private lottos to compete in.

Any Rawlsians care to share their views on gambling?

Unless you live in Alabama, Alaska, Hawaii, Nevada, or Utah, apparently.

As we know, there are no lotteries in Alabama. The tipped ticket was Floridian.

Counterpoint here:

Relative to matched controls, large prize winners experience sustained increases in overall life satisfaction that persist for over a decade and show no evidence of dissipating over time.

There are exceptions here. Peter Vallentyne notes that most libertarians would grant that it is permissible to tax a rights-violator to cover the cost of rights-enforcement.

Here’s o3 having a go.

Very bad take. I get some intrinsic enjoyment out of buying the ticket itself even if I do not win. In fact the primary purpose of whenever I buy the ticket is the anticipation and act of scratching or playing it, plus these things are like 2-10 bucks anyway so I feel like it’s worth u money to spend 2 dollars to have the feeling of mabye winning whatever. Don’t even have to win, just gotta know it’s possible theoretically and thats enough for me. If the prize shifted from money to like ice cream cones I would play regardless.