The "Lazy Hypothesis"

Rejecting the mainstream take on Midwest poverty

A while back Nick wrote about economic mobility. It immediately got me thinking about how I could spin the “fading American dream” thesis positively. It’s not that Nick took a pessimistic angle on the data, but that Raj Chetty’s findings supply the ammunition for such a conclusion so well.

That’s why almost everyone you talk to cites him when they try to convince you that the American Dream has died. Lately, I’ve become quite sick of the argument. Now, both leftists and rightoids are making it, for different reasons.

In case you don’t know, this paper by Chetty found that economic mobility has gone down for every group over time.

If you want to know more, read Nick’s article.

Seems pretty bad, doesn’t it?

Perhaps for a pessimist. Back in March, when he posted this, I immediately began thinking about how Chetty’s research could be wrong. I found this: page 7 of Chetty’s famous The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940:

“We exclude immigrants in order to have a consistent sample in which we observe both parents’ and children’s incomes.”

So that terrible-looking graph doesn’t include immigrants. Why does that matter? Because people sailing across the ocean, leaving behind their impoverished countries for a brighter American future, is an integral part of the American dream! For research purposes, I understand why Chetty left them out, (it’s hard to track down the parents’ information) but for practical argumentation, saying that the American Dream has been fading away (the most common interpretation of his research) is misleading. He’s leaving out the economic mobility of a sizable portion of the US! (14% of our population is foreign-born)

So I had this little point, but I didn’t feel it was enough for a blog post. Until I thought of the lazy hypothesis.

You see, many people being left out of the American Dream is only the 2nd most important point. The more important one starts by looking at how well immigrants are doing today.

The average Haitian income is $1,760 USD a year. Whereas Haitian immigrants in the U.S. have a median income of 65,000. Mexicans have an average annual income of $20,340 USD. Their immigrant counterparts are sitting at a median of 64,500 USD. South Korean households make an average of 46,000 a year, whereas the median South Korean household in the U.S. makes 93,600 a year. Indians have an average income of $4186 USD per year, while Indian immigrants have a median annual income of $166,000!

In a rough way, this shows incredible mobility. Being a place where you can come from an impoverished country like Haiti and make 65,000 a year is an incredible accomplishment for the United States, even if the mobility is cross-national, not intra-national. And remember that the immigrant numbers I have cited are all medians, not averages, so it really is descriptive of how immigrants are doing.

And it has been rising over time. In 1980, immigrants’ median household income was 42,473. Going by decade, it went to 52,893, (1990), then 57,561, (2000), then 52,829, (2010 great recession hurt) and in 2018 it bounced back to 59,000. (converted all to 2018 dollars) Looking at the present(ish), immigrants’ median household income in 2023 was approximately $78,700, slightly higher than that of U.S.-born households, $77,600!

This is incredible. People who are born speaking a different language, following different norms, with barely any money, are beating natives! Even being in the ballpark would be an accomplishment when you think about all the disadvantages they have compared to their native counterparts.

None of this is included in Chetty’s research on the American Dream.

I understand it’s hard to track down tax data on Nigerian moms and dads in the 70s, but it’s not impossible.

Introducing a bit of rigour to the argument are Michael Clemens and some others. In their article: The Place Premium: Wage Differences for Identical Workers Across the US Border, they find that nearly identical Haitian or Nigerian workers earn 5 to 15 times their home-country wage in the United States. These aren’t direct father-son links, but they’re the best economists can do, and I don’t find it a stretch to say that the enormous gaps here do imply enormous generational mobility for first-gen migrants.

This is getting more into Chetty’s research, but I would like to highlight the mobility between not just the parents of immigrants, but also the parent-child relationship between 1st and 2nd generation immigrants.

A team led by Abramitzky & Boustan linked father-son pairs for three cohorts (1880 to 1910/40, 1910 to 1940, and ~1980 to 2010). They found no downward trend for immigrants at all. Children of immigrants starting in the 25th percentile end up 4–8 percentiles higher than comparable children of U.S.-born parents in every cohort studied. So the immigrant mobility premium, handed down by the grandfathers and fathers to 2nd generation immigrants, is remarkably stable across 140 years.

This whole discussion is not actually the point of this essay. But I wrote it for 3 different reasons.

First point: Contra Chetty and almost everyone else you talk to on the street, I think the American Dream is underrated. Once you include immigrants, upward mobility becomes more common in the data. Chetty’s 50% figure (see graph above) doesn’t include immigrants or their parents. You might argue back that if immigrants had roughly the same mobility the last 100 years (plausible) that the graph would be the same. However, the graph is taking a slice out of the American population, and immigrants have been steadily becoming a larger share of the population every year since the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act was passed. Today they are 14%.

So their omission is important. And to finish this point, there is perhaps an even bigger reason why discussing the mobility of immigrants is important: because when people who have it much worse than you can still find a way to succeed when you do not, mobility looks a lot more achievable. (That could be phrased much more harshly, perhaps should be)

Second, more minor point: I am, after all, a reptilian skinned globalism fan big supporter of immigrants, as they are the most underrated group in American history by a mile, (yes, better than the 1992 Dream Team, Suffragettes, Apollo 11 crew, The Doors, first responders, etc) and I wouldn’t lose the chance to brag on their behalf.

And thirdly, I needed to discuss all of those stats so that I could neatly segue into my real argument:

But first, a question.

As I alluded to in the first point, it seems that immigrants are beating natives. But are they really? I want to hammer this home because it’s the biggest premise in the upcoming argument.

Chetty concludes that natives have had downward-trending mobility. These trends haven’t seemed to affect immigrants. They are winning with less:

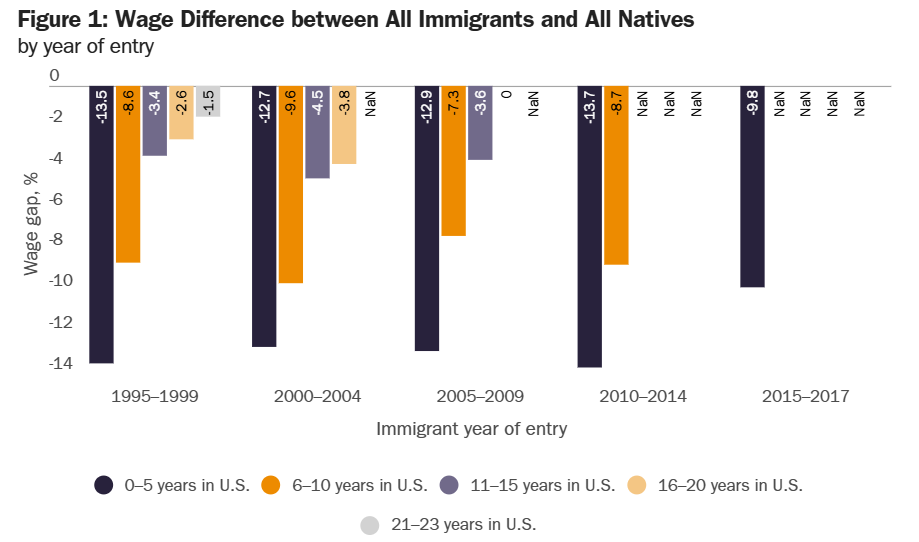

“Immigrants often start their U.S. lives at substantially lower earnings, but experience faster earnings growth than natives with comparable years of education and experience.

Another source confirms more aesthetically that immigrant wages converge, despite early assimilation problems (that natives don’t have).

The reason they often start much lower is because of transferability problems between country-of-origin skills and country-of-destination demands. Or in other words, assimilation is hard, and even harder for a Mexican than a Canadian. This theory is highly intuitive because you can see the transferability problem in the data:

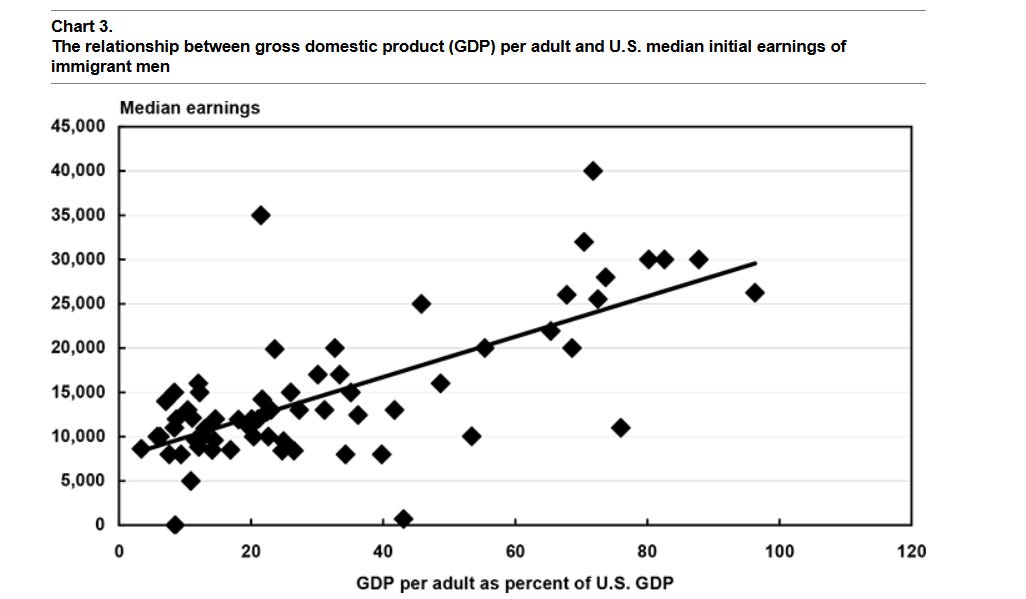

“Immigrants from Asia and Central and South America initially earn about half or less than half of what U.S. natives earn, whereas the entry earnings of Western European immigrants resemble those of the U.S. born. Moreover, these differences persist within age and education categories.”

Another way to think about this: Just a few paragraphs ago I talked about how median immigrant household incomes have been rising steadily over time. But the demographic makeup of immigrants since the 1970s has been, more and more, slanted towards countries with lower GDP per capitas, (less Germans, more Hondurans) so more transferability problems, not less. And yet, they have been rising, and now have a higher median than natives!

Now that I’ve demonstrated that immigrants are indeed beating natives on mobility grounds, here is the argument:

Downward trending mobility for Americans is not primarily caused by greedy billionaires or neoliberalism, or too much bowling alone or cities not being bikable enough or the price of matcha being too high and on and on. It is caused, primarily, by laziness and unambition. It is a fault of character, which immigrants remind us of every day. They show that incredible economic mobility is possible, both in inter-country and intra-country situations. Acknowledging that it is mostly a character issue, not a structural issue, is essential for understanding that the American dream is still alive for those who want to dream it.

If that was too academically crass, then fine: Americans are being held back by their complacency and risk aversion. Many Americans want to simply get through their day, reside in the same area they grew up in, and live a fairly calm and muddling existence. At the margin, I think we should have less of that. Immigrants have less of that. That’s why they are more mobile, and why they succeed more.

Immigrants start more businesses.

“Per capita, immigrants are about 80 percent more likely to found a firm, compared to U.S.-born citizens. Those firms also have about 1 percent more employees than those founded by U.S. natives, on average.”

Indeed, during the period 1980–2000, when inflow of new immigrants was large, the foreign-born population responded much more strongly than did the native population to differential employment growth across labor markets. As a consequence, highly successful cities became cities with higher immigrant density by the year 2000. In the period 2000–2017, which includes a deep recession and strong recovery and during which new migration from abroad declined and the long-term immigrants became a more sizeable group, the foreign born population still responded more than proportionally to local growth in labor demand.

“Internal migration has fallen noticeably since the 1980s, reversing increases from earlier in the century. The decline in migration has been widespread across demographic and socioeconomic groups, as well as for moves of all distances.”

Selection affects people! Those who migrate are going to have higher risk tolerance. That’s fairly obvious. And it pays out. Moving to places where your skills are in demand is one of the surest ways to increase your income.

I thus feel very little sympathy for the socioeconomic problems most Appalachian people’s face, especially when JD Vance is the one narrating them. That area has some of the longest-lasting families in the country. That’s not something to brag about.

If they had more of an immigrant’s ambition, JD’s hillbilly’s would have moved long ago, and been better for it.

That’s rich coming from me? Okay, give your reasons to the average Bangladeshi garment worker who moves across the planet to triple his wage, or the abandoned Mexican mother who illegally swims the Rio Grande with her baby on her back, or the Syrian father who sees his entire village destroyed in civil war and uproots his entire 7-person family, or the Cuban girl who goes to school to be a microbiologist but gets paid the same as a janitor, so she takes a boat across the sea to make a new life in Miami and on and on and on.

All of those people can’t even speak English, but somehow make it to Austin, yet you can’t make the 10-hour drive from Mobile?

Our society has embraced complacency at the cost of competitiveness and success. Excuses turn into reasons, turn into crystallized habits, turn into generations of muddling through, perhaps even poverty eventually.

Of course, policy can fix this. Zoning in high-growth metropolitan areas needs to be reformed. The cost of housing is the biggest barrier against intra-national mobility. Perhaps we could even look at relocation vouchers.

It is incredible to me that American mobility has collapsed, seeing as technological innovations like the interstate highway system, smartphones, and Indeed have made economic mobility much easier than it was in say, the 1930s when it was so much higher. They shave search and switching costs by orders of magnitude. And yet, immigrants are, on average, exploiting these new advantages at a much higher degree.

What reason could there be besides laziness? Immigrants are still behaving the way Americans once mythologized themselves: mobile, entrepreneurial, adventurous, relentlessly upgrading.

So thank God for immigrants. They remind us every day of how much better, how much more American, we can be.

Cowen’s First Law: There is something wrong with everything (by which I mean there are few decisive or knockdown articles or arguments, and furthermore until you have found the major flaws in an argument, you do not understand it).

I find this law most useful when looking at one’s own arguments.

The weakest part of this essay is my confirmation bias. Probably because of a mix of genetics and environmental effects, I am wary of giving credit to reasons not to do something, when I can see myself doing it or have done it in the past. Maybe this is a libertarian folly of thinking that because I can do it, someone else can. A leftist would reply that everyone is different, and comparing to others is unproductive.

For example, my take on addiction: I don’t have much sympathy for addicts. It seems like the popular take is to put most of the blame on producers, then users, and lastly addicts.

I don’t buy this. Opponents say that drugs like fentanyl and social media can literally rewire your brain, but so can learning how to dribble a basketball or play guitar. Brain modification is not reserved for drug use. I look at most of these opponents’ reasons and find them to be excuses. In my view, most addicts have terrible impulse control, and it is, for the most part, irresponsible decisions that have led them to their current state.

Of course, this mindset influences my writing on the mobility issue. I want to be transparent about that. I am naturally going to blame the person, not the structure. Accountability and agency are core heuristics for me. Perhaps it causes me to overlook structural problems, which make up a larger share of the causation.

The great Jimi Hendrix speaking in an interview:

“We’re trying to get across communication with the old and young. And plus we try to get across laziness on anybody’s part. And that takes a few more songs and a few more gigs to get that across really strong enough. I see people just get stoned and sit around and all they do is protest and not really wanna do anything about it. I said listen you can be a dishwasher until you finally get yourself together and they say “yeah but, you know, ughhhhh.” They don’t really wanna know about that. I know where the trouble is. It’s laziness. The people have to realize this or else they’re gonna to be fightin’ for the rest of their lives.”

“I have no tolerance for lazy teammates… If I’ve got to fight to get you in the gym, that’s a problem… You want players who are gym rats, players that want to work.

If you’re lazy, man, I don’t wanna talk to you. I don’t wanna deal with you. You’re gonna make me feel dumber, you’re gonna lower my level. There are plenty of other teams where you’ll fit right in.”

Jimi was born in Seattle. Kobe was born in Philadelphia. They are exemplary Americans, whose lifestyles should not be so easily forgotten. How many Americans would be better off if they had 1% of their risk tolerance, their proactivity, their aversion to laziness? They are the model. And so are immigrants.

PS.

I am being quite harsh on Americans here. That is because I think the best way to get better is to compare yourself. Get better then your last rep and all. But if you look outside of America, you will realize Americans are still incredibly mobile, especially compared to Europeans.

Above, I quoted the Federal Reserve as saying that:

“Internal migration has fallen noticeably since the 1980s, reversing increases from earlier in the century. The decline in migration has been widespread across demographic and socioeconomic groups, as well as for moves of all distances.”

I left out this part:

“Despite its downward trend, migration within the U.S. remains higher than that within most other developed countries.”

Don't the selection effects overthrow the whole analysis? Garment workers who drop everything to make for America are entrepreneurial and comparing them to the median American is silly, because they've been selected from the tail of their home country's risk distribution. There's no inspirational story here, because populations aren't going to up and change their risk levels.

In fact, it's possible (likely?) that America already has a right-shifted risk distribution compared to the home country. Sitting as the median American, this seems identical to telling me to be more like 'those guys in Silicon Valley', but it doesn't explain why I have to do that now, when it wasn't required before. Perhaps the story there is lethargy, but comparing the 50th risk percentile American to the 99th percentile Bangladeshi doesn't seem like the way to show it.