Must We Do Better Than Our Parents?

The great immobilization

…but it must be utility in the largest sense, grounded on the permanent interests of man as a progressive being.

J.S. Mill - On Liberty

There seem to be two conditions any such interest must meet:

(i) An interest in the social conditions that are necessary for the continual progress or advance of civilization until the practically best state of society (morally speaking) is reached.

(ii) An interest in social conditions that themselves are conditions of the best state itself and required for its operation. These conditions are necessary if it is to remain the best state.

John Rawls - 4th Lecture on Mill

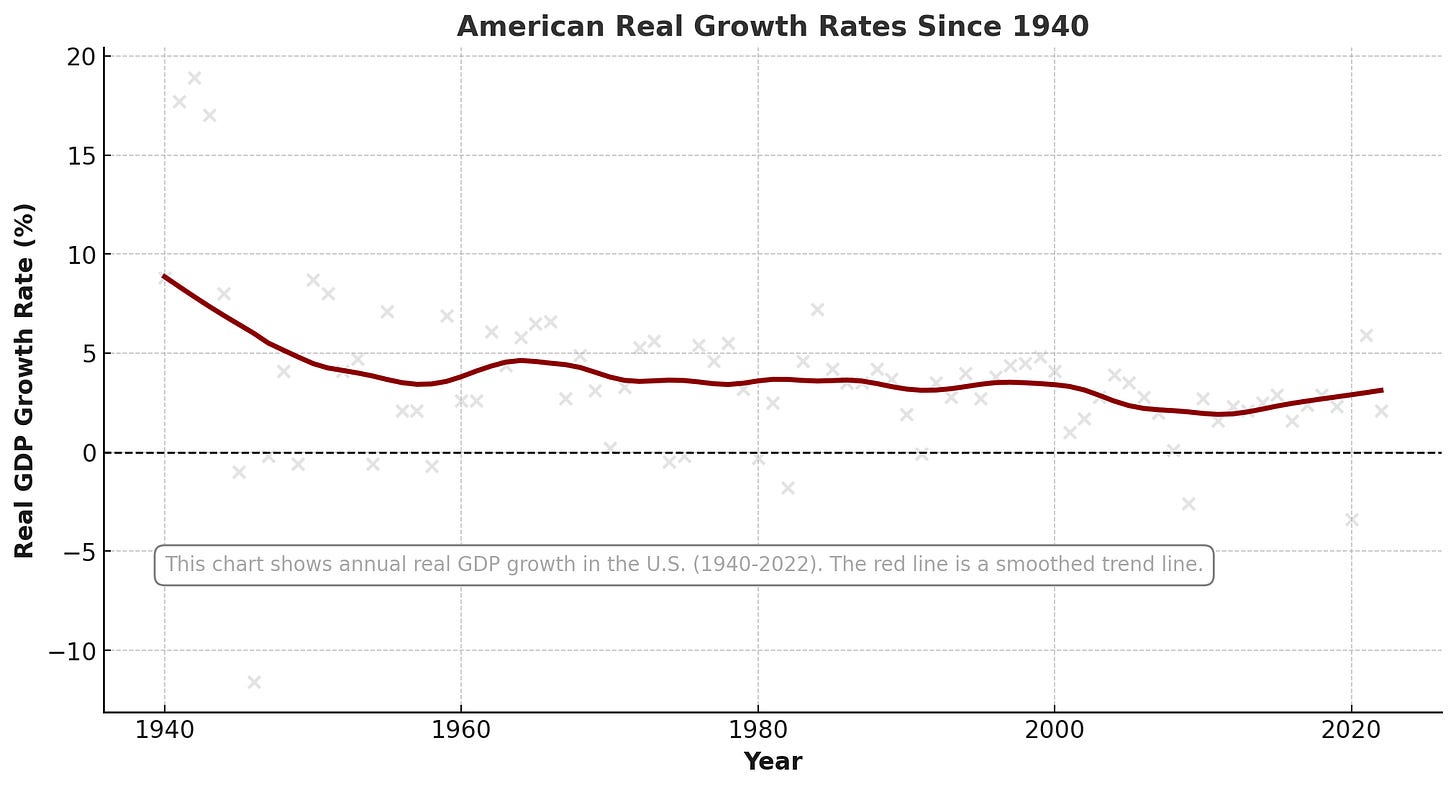

For a large number of people, this is a deeply disturbing graph. Should it be? Let’s explore the arguments.

Yes—it is a feature of our psychology that we want to do better than those that came before. We are, as Mill wrote, progressive beings. A meta-analysis found that upwardly mobile individuals experienced fewer mental health problems than those who were stuck with low socio-economic status.

No, it’s not disturbing. That same meta-analysis found greater mental health problems for the upwardly mobile compared to those stuck with high socio-economic status. More people today are in this higher status bucket, so we don’t need upward mobility like we used to.

That might be true if (1) upward mobility was still available at similar rates to those born with low socio-economic status and (2) downward mobility was not increasing. What does the research say?

Working from this paper by Chetty et al., we see that relative upward mobility is less available than it used to be for low-income white children, more available than it used to be for low-income black children, and has remained relatively constant for low-income children in other groups. Relative downward mobility has declined among the upper-income in step with these changes.

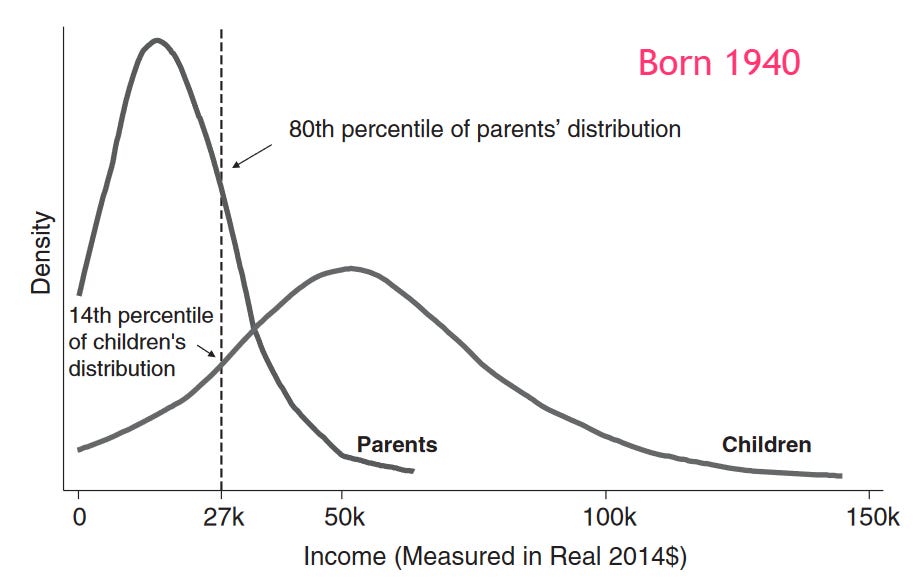

There’s this other Chetty paper that has more to say about absolute mobility. It shows that it has declined drastically for every group, though the losses have been less pronounced for lower class families. There, the children born to bottom 10% families have seen their odds of earning more than their parents fall from 94% to 70% over time.

The picture across the two papers is not a movement from big upward swings in the 50s to big downward swings today, but rather a stickier, more static world. The rate of large moves in either direction has declined.

So yes, we should be disturbed because this means life outcomes are becoming increasingly shaped by the lottery of parental status. That’s unfair morally and inefficient.

No—to the contrary, this is consistent with a society shaped by our natural talents. The spread of quality public education and the alleviation of absolute poverty since WW2 has freed people up to meet their potential and assortative mating has run its course. Given the removal of unnatural barriers, what we’ve moved into is the equilibrium. What’s to be done now is to harness the gains enjoyed by the talented to compensate the untalented, since neither group earned their place in the lottery.

If this were true we would expect changing a child’s environment to do little for them economically, since parents have sorted by talent and children tend to reflect their parents’ genes. Basically, moving children from low mobility to high mobility neighbourhoods shouldn’t change their outcomes.

Chetty’s team studied a large sample of children that moved counties and compared the results of children who moved at younger ages (and thus spent more time in their new county) with those who moved older. They found that the younger the children moved to high mobility neighbourhoods, the more upward mobility they experienced over the course of their life. In families with multiple children, the younger ones consistently benefitted more.

No demographic differences existed between the younger and older movers, so there doesn’t seem to be a selection bias. Rather, time spent growing up in high mobility neighbourhoods seems to cause children to be more upwardly mobile. Ergo, the natural talents account seems mistaken.

More reason to worry: birth rates have been falling over this period. Parents today can expect both a smaller percentage of their children to exceed their position and a smaller absolute number of children doing so. For parents, that lowers expectations about what to expect in terms of elder support: less potential caregivers, each of whom are less likely to be able to maintain your quality of life.

Your graph earlier showed positive economic growth rates, how does this square with declining absolute mobility?

In brief, growth is now distributed with a top-end skew, leaving less growth available for lower and middle-income children to capture. Without growth capture, it’s not possible to do better than your parents at the aggregate level.

From Chetty’s ‘The Fading American Dream’

This is not like poverty, where scholars hide behind bad relative measures to obscure substantial progress towards eradication. Absolute mobility is vanishing, fast.

If we accept that low mobility is mostly arbitrary and thus unfair, we might ask why it happened, to gain insight into what might be done about it. There seems to be a Bowling Alone-type story to tell here about declining amounts of cross-class friendship. Rising incomes mixed with suburbanization to enable greater residential segregation by class, while at the same time, churches, clubs, and other community organizations saw their participation rates plummet. These conspired to eat away at the opportunities for such friendships to form.

Chetty has two papers on cross-class friendships and the strong degree to which they predict upward mobility. The first lays out the case for this being true, while the second explains what causes these friendships to form or not form.

The relevant aspect for low-income people is that they befriend across class lines, not high social engagement per se. Areas with the most cross-class friendships are the most upwardly mobile, and moving as a child to Salt Lake City or San Francisco would be expected to raise your adult income by 20-25%.

These friendships appear to be the mechanism through which income inequality and segregation hurt mobility. As those increase, the friendships dry up.

Desegregating spaces doesn’t solve the problem, because people have a friending bias—that is, a tendency to befriend within their socioeconomic group. The bias is weak inside of churches (but those have declined enough where that doesn’t help much).

My own intuition was that clubs would have a low friending bias—shoutout Model UN—and they indeed have the second lowest in Chetty’s study. With that said, I have no idea how to get more people to join clubs…

What do you think about all this? Do you think about this? Let me know.

I really loved this comment from /u/UtridRagnarson on Reddit:

I have been reading Horatio Alger novels to my sons and I think he captures the phenomenon quite well. Every one of his books is roughly the same. Some naturally talented young person is living in poverty. The young person meets respectable upper class or upper middle class people who recognize his talent and encourage him to apply himself. They also give him important information for "moving up in the world." Then the young protagonist rises economically and socially.

People on the left in Alger time and later lampoon this as unrealistic and idealistic. Ironically, though, our contemporary society is actually crueler than a leftist caricature of gilded age America. Horatio Alger protagonists work as boot blacks, match boys, or news boys making small sums of money in an entrepreneurial way. All of these jobs are basically illegal because of various regulatory constraints, tax requirements, and labor regulations. All protagonists live in boarding houses where a tiny room with no amenities could be rented for a very small amount of money. Such boarding houses are illegal almost everywhere now. Horatio Alger protagonists live in areas where they mix with business people like NYC. Now educated elites are concentrated in exclusionary suburbs, unaffordable elite cities, or car infrastructure inaccessible to the poor. It's hard to imagine any cross-class mentorship happening. Educated elites, when they go to church at all, attend churches in their suburbs that a poor young person living in a nonexistent boarding house would have difficulty reaching. Maybe we mix on the internet, but such interactions are largely impersonal and anonymous.

The one area where we surpass Alger is in education. Horatio Alger boys study at night or engage tutors to improve themselves educationally. However our education system is also rather isolating. Students learn in groups of exact age peers. We obsess about how to make sure these peer groups are as good an influence as possible because they are doing a lot of the work of acculturating our children. We don't have bosses and coworkers introducing children to adult life, only other children. Their only adult contact is with teachers who are, themselves, isolated from career opportunities and the functioning of the economy outside their (often dysfunctional) bureaucracy. In Alger novels, education is a way to show that you are conscientious and gentile, not a path to success in and of itself. It's also something precious and chosen, not something force on bored children as a form of child-care.

In the end, I think we are hypocrites. We laugh at rags to riches stories as outdated or part of a toxic pull yourself up by your bootstraps narrative. Meanwhile our own institutions are significantly worse. They deny the old channels for upward acculturation and economic mobility while failing to provide anything to replace them.

DO YOU NOT WANT MORE MONEY