The Good, the Bad, and the Automated

An unapologetic case for our economic obsolescence

This is the more speculative sequel to part 1. That dealt with the immediate effects of robots in the next 5-10 years, which you can find here. This one is more fun, though.

If robots “take a lot of jobs” in the next 5-20 years, would that be good for the economy on net? I think so, and many of you probably do as well. But not all. Probably not most.

For example, the majority of workers are worried, not hopeful, about AI just being used in the workplace. Most think of automation pessimistically (it'll drive up unemployment!).

So most don’t think it’s good, on net.

But even among the minority who believe that it’s good overall, an even smaller minority believe in the next claim: that it’s both good on net and good for the people losing the job. Specifically, if you get your job stolen by a robot, it is not only good for the rest of us, but really good for you.

I will use simple economic history and theory to explain why such a strong claim is true.

Let’s start from the ground up. Will mass automation of jobs by humanoids and robots pass the cost-benefit test?

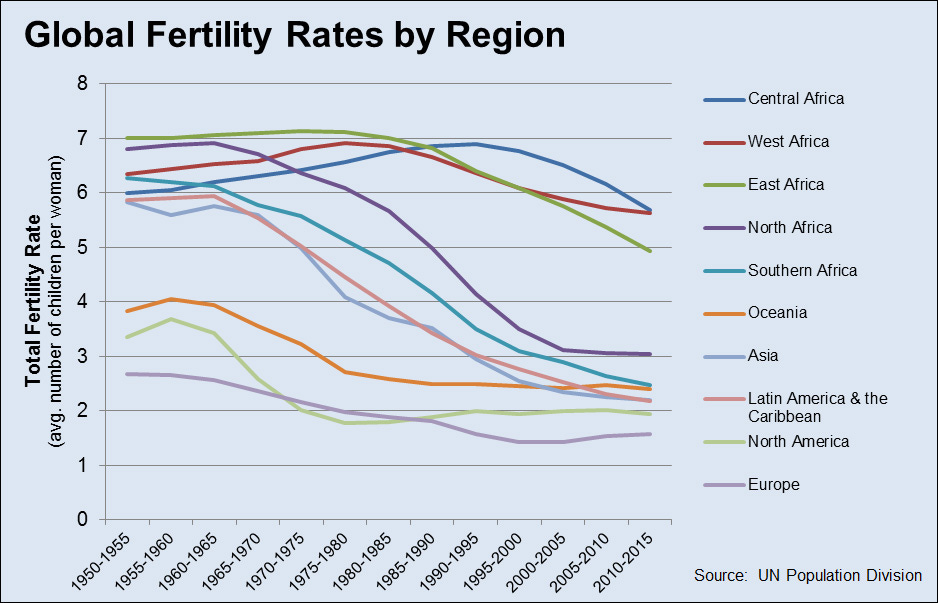

The biggest reason automation passes the test for our species is fertility, surprisingly. Because fertility rates are falling at such drastic rates, roughly universally across our planet, robots are the only sustainable solution. Increased immigration is a band-aid and everyone knows it. For now, we can rely on Latin American and African immigrants due to their higher fertility rates, but soon that well will run dry too. And then we’re really screwed.

Of course this is bad. Whether you like it or not, we’ve all bought into a system where all of our social and political institutions, from pensions to healthcare to debt markets and even social stability, are predicated on the assumption of continued economic growth. If fertility plummets, growth falls with it, and thus the system unravels. And this doesn’t even get into the negative effects on innovation, perhaps the most important point regarding fertility rates.

I’m not going to go into detail on this point, because it’s an essay in itself, and I’ve already written itThe point is that falling fertility rates are an issue that needs to be solved, and immigration, as shown by the graph, is an extremely temporary solution.

Luckily for us, a permanent solution is just beginning to show itself. And I’m not the only one who thinks this, nor am I just referencing some crazy bloggers. Many governments have subscribed to this solution too.

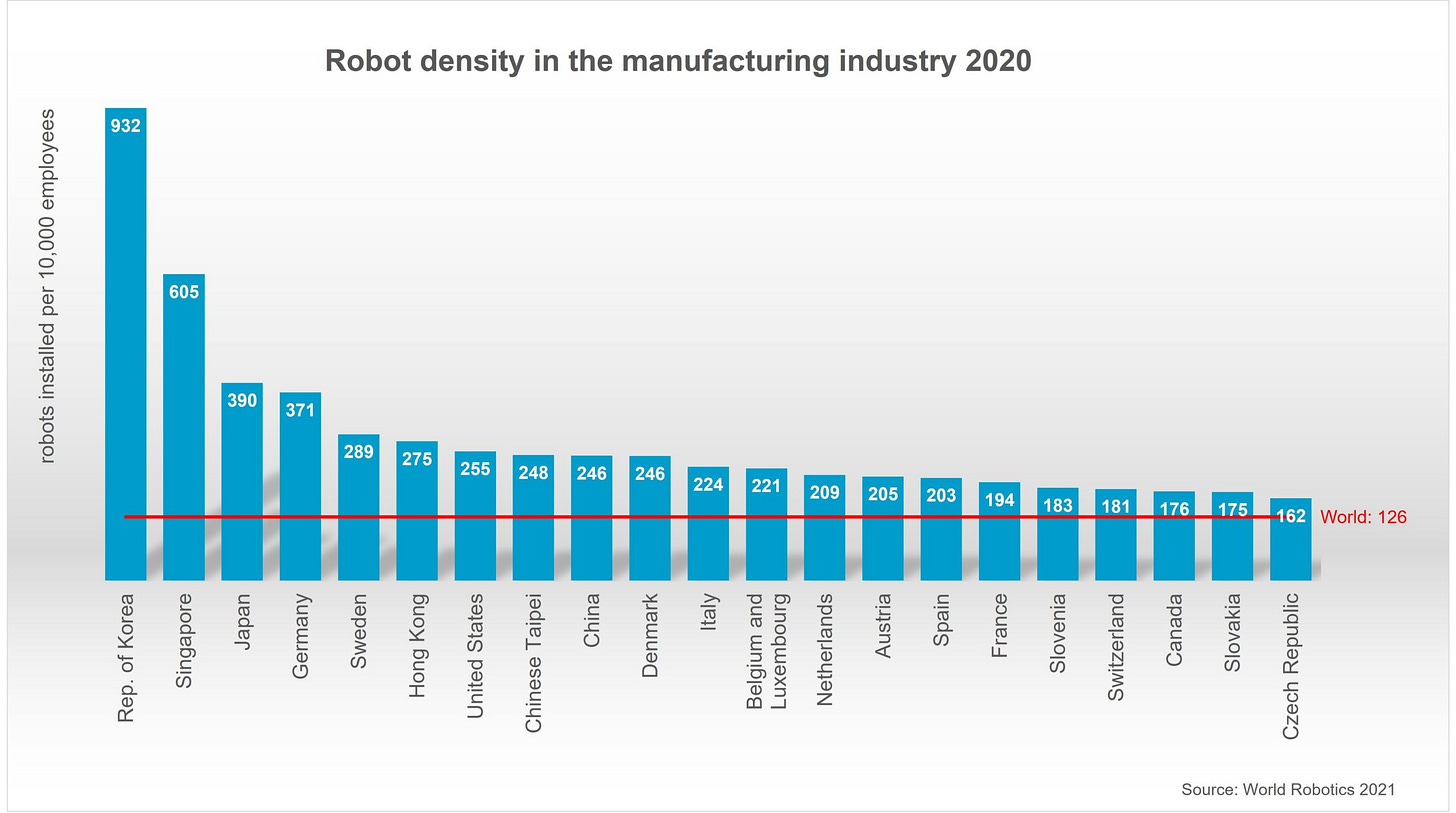

Japan is using robots in nursing homes and elderly care centers. South Korea too. China is no different.

“China is witnessing a rapid integration of artificial intelligence and robotics into eldercare services, offering innovative solutions to the challenges of an aging population.”

So not only does this solution sound good in theory, it’s already being bet on by multiple governments. More than anything, it’s common sense. Falling fertility rates mean each retiree must be supported by fewer and fewer workers. You can either (a) persuade millions of adults to have more babies, (a 20-year lag before those babies join the labour force) or (b) add productive “workers” that skip childhood entirely. Robots, cobots, and AI systems do the latter overnight. Immigration does it slower and is unsustainable anyway.

Or, to phrase it negatively, lower output per worker shrinks the tax base. So if you don’t get that productivity bump from robots, governments face the ugly trio of higher taxes, benefit cuts, or heavy immigration, all harder political sells than “buy more robots.” I guess an alternative would be a cultural revolution spurring higher fertility, but I don’t see anyone arguing that would be easier to achieve than my plan, for obvious reasons.

And then there are the more standard arguments for automation, which aren’t as novel because they’ve been around since the 19th century. So I won’t dwell on them.

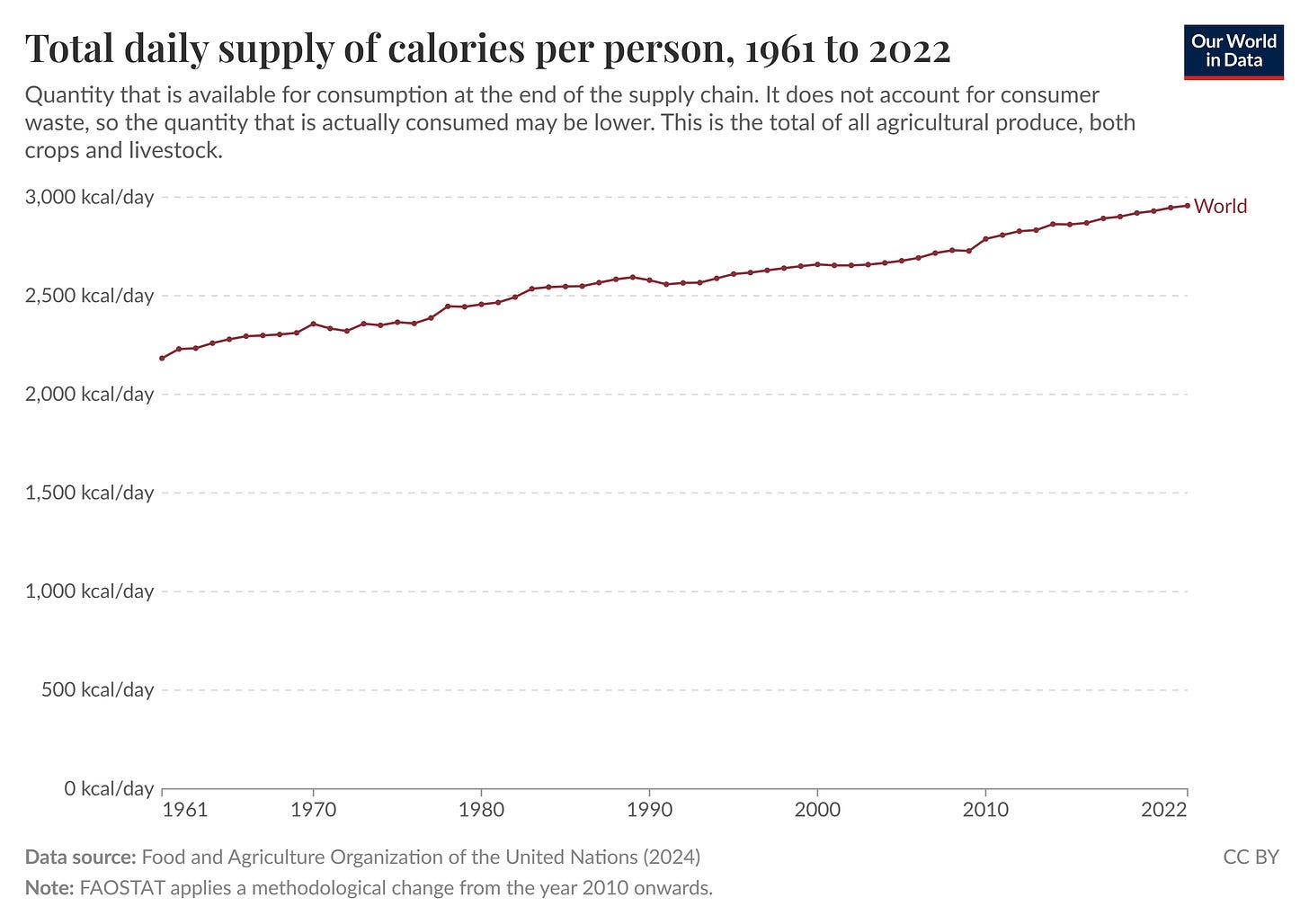

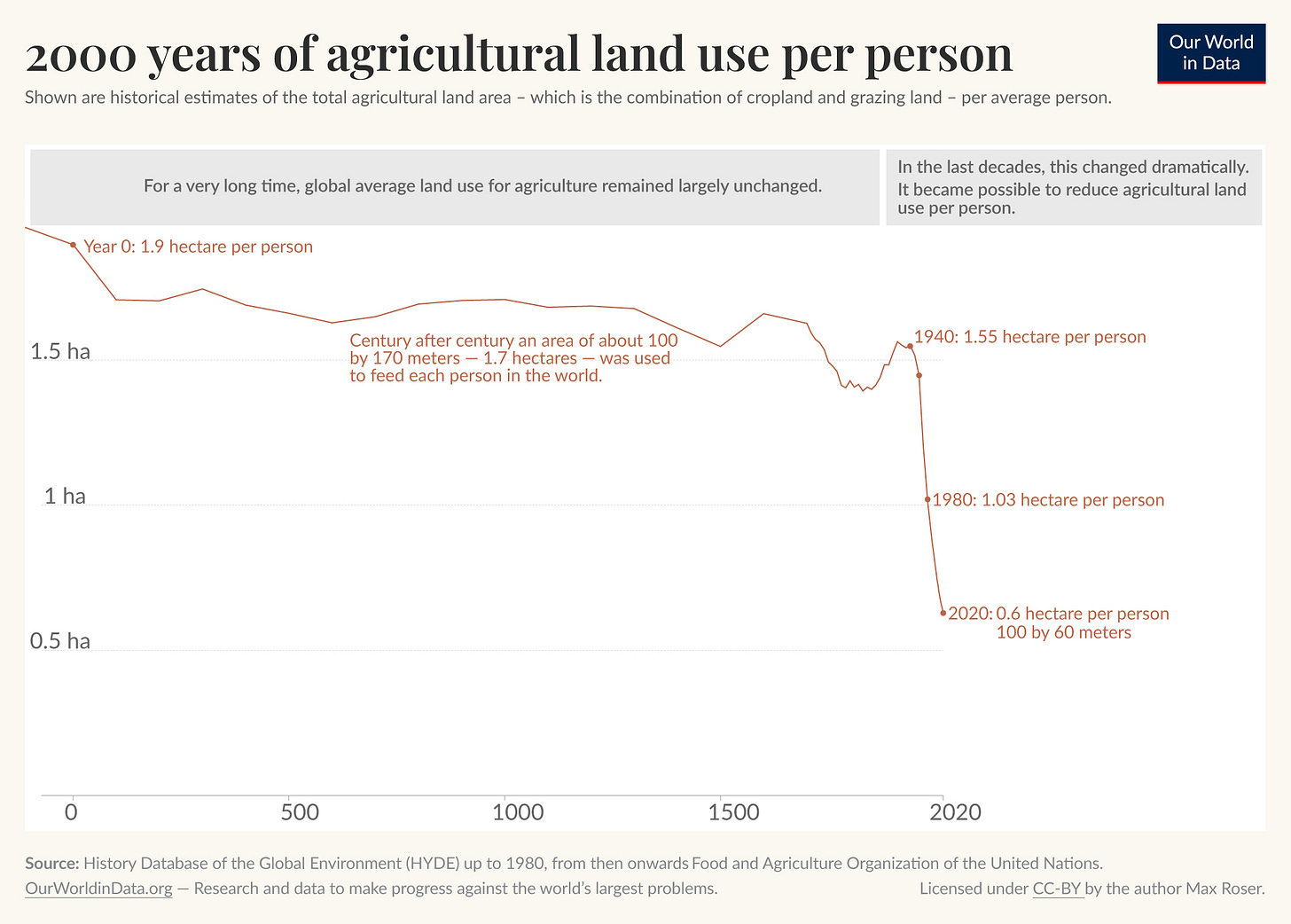

But obviously, automation has gone splendidly in the past. In 1900, roughly 40 % of U.S. workers farmed; today it is < 2 %. And yet, the world is better fed than ever. Land use per person declined by more than half in the past few decades too. At the same time, food supply per person increased in every region of the world. How is that all possible?

The answer is of course the glorious TFP, the most important acronym in the English language.

Two points here. Not only did automation (which was not the only factor here, to be fair) help to increase productivity in agriculture (which thus allowed us to produce more food at a lower cost with fewer people) it also freed up almost 40% of the U.S. labour force. Notice I said freed up, not stolen, and not unemployed, because it instead allowed for the birth of the service industry, which today feels so commonplace it’s hard to imagine it pretty much didn’t exist in the past. And it was allowed to exist because people were rich enough. (in real terms, because food had gotten cheaper)

They were rich enough to afford to get haircuts and watch movies and go bowling and so forth. It was automation that allowed for that extra wealth, which allowed for new jobs to be created.

The Spinning Jenny, again, wasn’t bad on net. It and other subsequent inventions opened up an entire industry, called clothes shopping! Again, real incomes rose and new jobs opened up to cater to these wealthier consumers.

I’m going to stop now, because I know you’ve heard all this before. It’s just incredible that something so obvious, a pattern so consistent, can be so easily forgotten. It causes initial pain for those whose skills are rendered obsolete, but ultimately leads to a dramatic expansion of prosperity and well-being.

So we have this historical pattern. Some might say, sure, a lot of technology has been good in the past, but what about OxyContin, fentanyl, and social media? That isn’t such good technology, so argument defeated!

Well, we’re talking about automation, not just new technology. Automation has had an exceedingly good historical record. And even technology in general has been, subtracting the bad and adding the good, overwhelmingly positive. You know that, you’re just trying to be pesky.

But this time will be different, you say. Sure, automation has created prosperity almost all of the time in the past, but this is the last stage of automation. Doesn’t that imply a more extreme effect than ever before? Perhaps catastrophe?

This is just simple risk aversion. I see no rationale behind fearing the final point of something simply because it is the final step. End the chain of causation does not mean the world explodes, but for a brain that evolved in a relatively static East African environment, I can see how that can be an impulse.

But c’mon people, how likely is it that a consistent trend suddenly has a completely different and catastrophic outcome at its final stage? There’s an inconsistency in thinking that if a process is beneficial and predictable for its entire duration, its conclusion should be anything other than a predictable and logical end, most of the time. This is just simple probability.

When a train makes a journey from New York to San Francisco, why would you expect it to suddenly combust once it finally reaches its destination? No, because you have taken trains before. But imagine you didn’t, and you were trying to predict what would happen. Obviously, the sane prediction is that it would do what it has always been doing, (going west) and once it reaches San Francisco, instead of the world exploding, it simply, stops going west.

I think the fear isn't just of a generic catastrophe, but that the drama of the finale itself implies a negative change. But the dramatic finale can be the ultimate payoff!

Basically, I want you to update your probability upwards of automation being good because 1) it is the best solution to the fertility crisis and 2) it is likely to be exceptionally good for economic growth.

Now we get to the 2nd claim. Sorry for the wait. So my strawman my steelman egalitarian luddite says “Fine, I’ll admit it’s probably good for the economy, but what about the people losing their jobs? Like those poor longshoremen being terrorized by capitalists trying to automate them. What a shame…

I personally love when longshoremen hold on to their jobs like medieval fiefdoms for the rest of their lives! I would rather preserve a few jobs of a vocal and politically active minority than marginally increase the utility of an incredibly large but disorganized majority. 10 times out of 10!

So I’ll never buy your “on net/cost benefit” arguments,” (murmurs under their breath that I’m an unemotional utilitarian) “nope, you’ll have to show me each and every person (no exceptions!) is eating berries and cream because of this, or else I’m anti-tech!”

I’ll start with the historical precedent. 98% of Americans are not farmers today. That number might have literally been reversed in 1790. Although it’s hard to imagine, automation can create entire new industries which were unthinkable just decades before large technological revolutions. Weird new service jobs have already begun to pop up in the most automated places like Japan and South Korea. In Japan, you can rent a stranger for a night out simply to give the appearance of having company, or to momentarily cure loneliness while your partner is away. Or firms that will quit your job for you if it makes you too uncomfortable. And there is a plastic surgery firm in South Korea that can give you elf ears.

But perhaps you just love the office work you do, and you know AI is going to take it soon, and you don’t want to just live off UBI, you love your job. Well, although you sound a bit crazy, I have a solution for you! In China, you can go to “fake work” where you can pay a few bucks a day to pretend to work!

According to a report in Beijing Youth Daily, although there are no contracts or bosses, some firms simulate them: fictitious tasks are assigned and supervisory rounds are even organized. For a fee, the theatricality can reach unimaginable levels, from pretending to be a manager with his own office to staging episodes of rebellion against a superior.

It is no surprise that these are found in the most highly automated societies, either.

What I am getting at is that the future will simply be as it has been: old jobs will pass, new ones will come, most of which you can’t predict. Humans value emotional connection, and for now, robots will not be able to steal that from you. And the best part is that these jobs will most likely be much better than the ones of old. It's rare that a robot completely eliminates a job anyway. More often, it automates the most repetitive, tedious, or dangerous tasks within that job. Or if it does replace a job, it is usually one that is boring or hurts your back, like tilling a field or vacuuming a carpet. This frees us up to do things that are meaningful, like take care of elderly people or children, or direct robots in creative directions, or simply go off and adventure in Spain on your generous UBI!

Think the last part is overly optimistic?

Why not? First of all, more automation means, like in the past, that real incomes will rise. (Goods and services will be much cheaper, so more disposable income). A keen observer of our political economy would comment that, knowing our society, the government will probably just try to keep protecting jobs even when robots could easily automate them. Governments are generally pretty confused about the value of jobs anyway.

Not only can we see “fake jobs” existing today, among us, but also in history, at even larger scales. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the United States during the Great Depression is a good example of this. The WPA employed millions of people to build public infrastructure like roads, bridges, schools, and trails. It even funded artists, writers, and musicians through its Federal Project Number One.

The creation of these economically useless but perhaps socially valuable jobs will dampen the rate of automation, and so too will unions and various labour laws. However, the cost incentive will be too great for capitalists to forgo, and over time, most industries will automate, especially those without strong unions.

As the ratio increases, corporate costs will plummet, profits will increase and so too will corporate tax revenue, which I would predict would then be turned into some form of UBI. However, because of market competition, profits will only rocket up momentarily, and for a select group of firms. Soon enough, rival firms will drive prices down. So this will decrease profits.

So, I would predict that capital gains taxes would actually be the main source of revenue for the government.

Or maybe a “Payroll-parity charge.” This is Bill Gates’ idea. For every task a robot does that used to trigger employer payroll/Social-Security contributions, the firm remits an equivalent charge. So you’re basically treating robots like employees for tax purposes.

Either way it shakes out, the main problem with UBI in the future will not be fiscal, it will be political. It is fiscal today, but if AI and robots can automate most human labour, it will generate an almost unimaginable amount of economic value and wealth. The exact mechanism for UBI revenue isn’t incredibly important if you buy the fast takeoff scenario. If you think it will be slow takeoff, then the automation of the economy could happen over the next 4 or 5 decades instead of the next 1 and a half. That would mean the mechanism is much more important, because you want to incentivize further automation with whatever tax you use.

Whatever the tax code, in the fast takeoff scenario, and even the slow takeoff, UBI is by far the best option. Think about the other leading future proposal, one with a good amount of popularity: a jobs guarantee. This would likely be inefficient, create a massive bureaucracy, and might even force people into unfulfilling work. UBI is a cleaner, more efficient mechanism. And it is the American way. Why? Because UBI’s main effect is the creation of true freedom for our species. For the first time in history, we will be able to choose how to use the time that is given to us, whatever way we see fit.

In the end, people will probably shift more and more to mindless consumerism. As they have been. Attention spans will get shorter, time outdoors will decrease, community will disintegrate. All of the trends we have seen will continue. People will be free to do what they want to do, in their virtual space adventures, in their tailor-made AI video games, with their digital wives and families. Many of us living today will look and be revolted at the future norms of this hyper-individualistic, hyper-consumerist society.

Just like past generations looked at us, and those before them.

It will be a foreign world, where people rarely speak in person, cook for themselves, or perhaps use their physical body at all. There will be exceptions. Amish types who choose to live “traditionally.” But the vast majority, thanks to well-functioning markets, will be supplied with a huge variety of services and products, and they will choose the ones that make them happy, not the ones that make you happy. If that creates mindless consumerism that our generation all hates, so be it. Curse them all you want. In this new age, other people’s feelings will finally be irrelevant. Money will be irrelevant. In a digital world, even reality will be irrelevant. True freedom will be created. You and I will be estranged from them, but that is fine. The alternative is control. I choose independence.