Electoral Reform Is Overrated

Trade-offs are everywhere

In the leadup to his 2015 election, Justin Trudeau pledged to reform Canada’s electoral system from its current first-past-the-post approach to something new. He won, some consultations were held, and the idea went into the dumpster. Some took this as the ultimate betrayal and held it up as the reason not to support his government in subsequent campaigns. I sympathize—it was a big flip-flop!

With that said, there’s a sort of person who tends to centre the idea of electoral reform as the root problem of contemporary democracy. Implement it and many ills would vanish. I want to go through some of their proposals and explain why they’re being naive–the trade-offs are always tough ones.

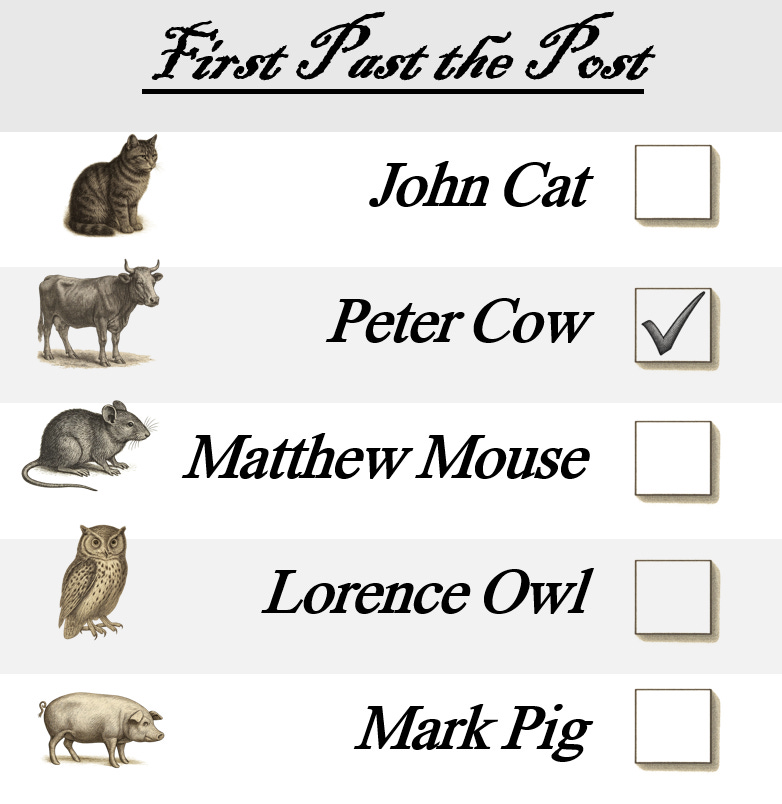

Problems with Plurality Vote (FPTP)

Let’s lay out the objections people have to the standard way of electing representatives to the House of Commons/Representatives/etc.

Disproportionality - I get the sense the British are acutely familiar with this one, which is the problem of a party winning two thirds of the seats with one third of the vote. The idea is that seat counts should align with vote counts if voters are to be substantively equal. In a country with very similar districts, a party could plausibly win all of the seats with less than 50% of the vote! This problem is caused not only by dispersed losers, but also by concentrated winners; surplus votes that run up the margin of victory don’t count for anything.

Unresponsiveness - Picking one candidate communicates a given voter’s favourite candidate, but it doesn’t capture anything about their feelings on the other options. Not only that, but it gives no way to communicate the strength of their preference. Lots of information is left by the wayside.

Less Choice - The electoral system a country rolls with can influence what options are available for voters. Plurality vote tends to create two-party-dominant systems, a relationship known as Duverger’s Law. When a third party enters the picture, they really only have two options: they spoil the chances of one of the main parties or their supporters strategize to avoid splitting the vote. This is perhaps most common criticism in the United States. Another manifestation of this problem is the conflation of candidate choice with party choice, since voters might have different preferences across the two domains.

Regionalism - Since two parties are nationally dominant, the best strategy for a successful third party to pursue is to specialize in specific geographic areas. Their incentives are to cater only to their region, not to the country as a whole. See the Bloc Quebecois and Scottish National Party.

Ranked Ballots (AV/IRV)

If you polled people on what electoral change they would make without providing any explicit options, ranked ballots would do pretty well.1 They’re an easy reform–you keep your current districts, the house stays the same size, and you get all this new information about how voters rank the candidates. But because it’s easy, don’t be surprised that it’s not much of a change from the status quo.

Here’s the method: On the ballot you rank as many options as you want. When the night is over and the votes are being tallied, first preferences get counted and they see if any candidate got at least 50%. If not, the lowest candidate is eliminated, and those who had them as first preference get their second preferences counted. This continues until a candidate secures a majority in the district.

It might not be intuitive, but ranked ballots can easily increase disproportionality, while barely improving responsiveness. There is little reason to expect them to improve on choice or regionalism as well. They are on a par with plurality voting and expending great energy on their advocacy betrays a passion for politics with no political substance.

Ranked ballots crush the centre. Picture a broadly appealing compromise candidate, Celia, who bridges the chasm between the two prevailing rivals in a district. People like Celia quite a bit and she ends up as the second choice for most of the rivals’ supporters. Unfortunately, she struggles to break through to become enough people’s first pick. When it comes to count the votes, it’s 35-35-30 and she gets knocked out first, despite aligning best with the median voter‘s preference.

Ranked ballots and disproportionality. Celia’s problem is present with the status quo, so it’s simply one that ranked ballots fail to improve upon. It’s not a problem unique to ranked ballots. For one that is, consider this story:2 three parties are running for office across the country. A and B are close politically, while C is on the other side of the spectrum. C routinely gets 40% of the vote, leading A or B to consolidate support to challenge them on a riding-by-riding basis. They do this imperfectly and C regularly wins a share of the seats approximating 40%. Under the new system of ranked ballots, A and B no longer have to play this strategy and routinely rank each other second, leading C to be wiped out across the country. This leaves C’s 40% lacking proportionate representation in the legislature.

Imbalanced responsiveness. An interesting feature of Celia’s election is that only those voters who picked her as their first choice actually get their second choices registered. Supporters of the two rivals don’t have second choices which matter under a ranked ballot, which will inevitably frustrate one of the groups, namely the one which loses. They’re left wishing their second preferences had been registered so that they could have at least gotten Celia, instead of their rival.

Non-monotonicity. Here is a weird property of ranked ballots. Return to the race between A, B, and C. The latter is still going to be the biggest party on the first ballot. Let’s say some A supporters are open to backing C, but all B supporters think that’s unconscionable and would switch to A if B lost. Who wins the election depends on if A or B is eliminated first—if A loses, then C wins the district; if B loses, then A wins the district. Taking the position of a C voter, it could actually be the best move to switch your vote to B, in order to make A lose and send their supporters to C. ‘Vote B to make B lose in the second round’. Non-monotonicity is the ability to decrease a party’s odds of winning by increasing its vote share, and it is a very weird thing to allow in your system.

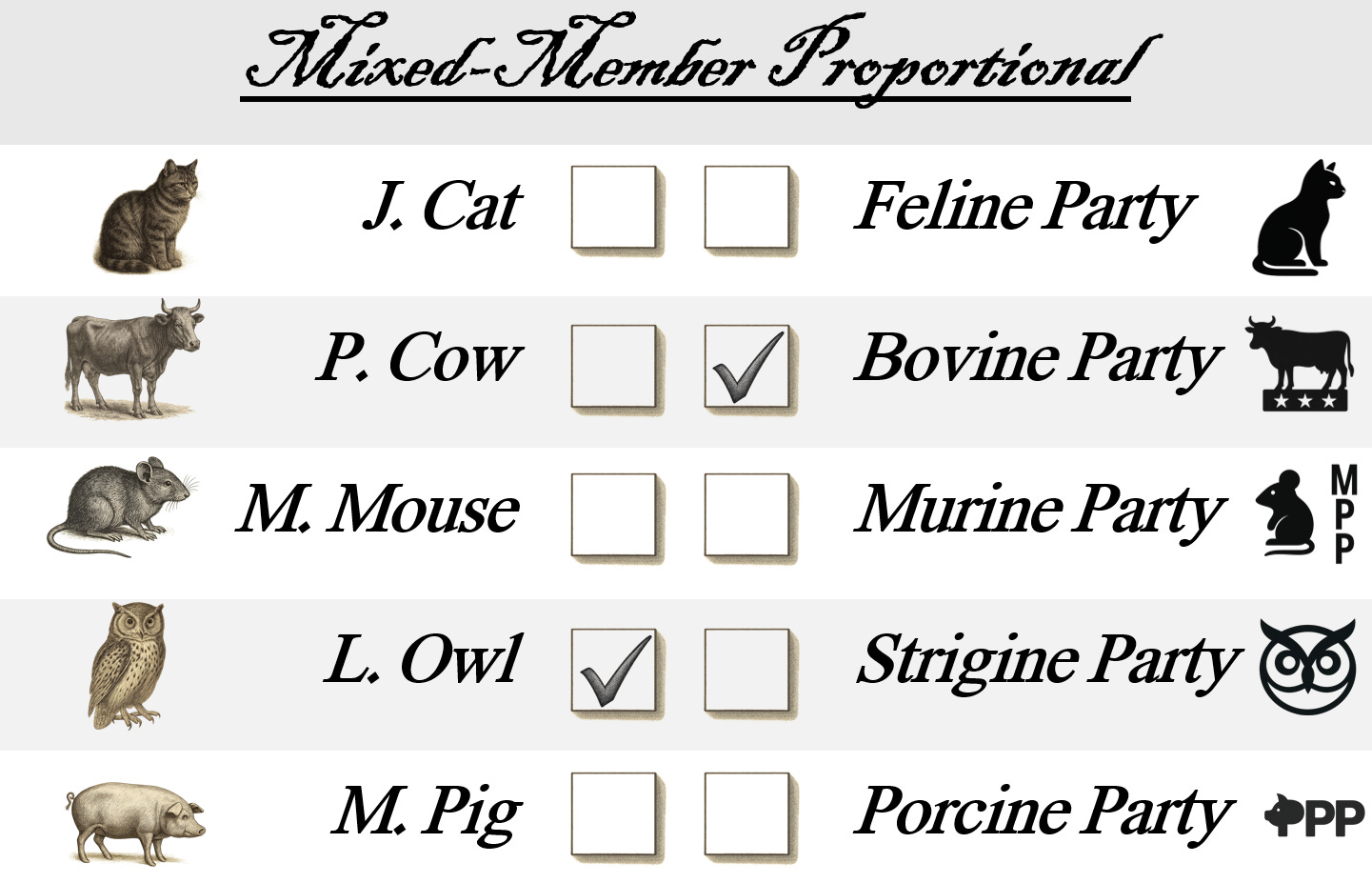

Proportional Representation (MMP)

Here’s a much bigger change we could make: give everyone two ballots. Or, more realistically, two columns on the same ballot. In the first column, the voter chooses the candidate they want to have represent them; in the second column, they choose the party they want to have in government. The winner of the first column wins the district and goes off to parliament, while the second column decides the national popular vote. Based on the results of the popular vote, extra seats are given to parties in order to bring their share of seats in line with their vote share, to be filled by candidates on a ‘party list’.

Because the seat count varies election-to-election and is whatever is sufficient to achieve proportionality, that class of concern is eliminated. That is unless you also introduce a minimum vote share to gain access to party list seats, as is done in Germany with the 5% rule.

Little extra responsiveness. MMP systems, as they are called, make one big improvement in terms of preference responsiveness by having voters fill out two ballots. However, they don’t let their voters communicate anything about the other candidates. So in the Germany case, SPD voters cannot convey that they really don’t want the AfD in government, that they’d prefer the CDU, and that they feel quite strongly about these preferences (and vice-versa).

Second class reps. You’re picked off the party list to have a seat! But who are you accountable to? Your colleagues won constituencies, but you owe your job to the party leader who put you on the list. It generates funny incentives.

Soupy accountability. Minority governments introduce a decidedly undemocratic mechanism into the electoral system—coalition bargaining. This closed-room process puts parties with different priorities into cahoots with each other to run the country for years on end, fuzzying mandates. It can give small parties extremely disproportionate influence when their votes are needed to clinch a majority, the kingmaker problem. Naturally such arrangements put voters, who want to judge recent performance, in a bind, because they can’t immediately determine which coalition partner(s) to blame or credit. The liberals? The social democrats? The greens?

Dubious efficacy. This will be contested, but there is reason to think coalition governments lead to worse policy outcomes. Proportional representation leads to weaker fiscal restraint, less legislative productivity, many veto points, and an innate incrementalism (on average). On the other hand, there is lots of variance in these effects and proportional systems tend to have similar growth rates. Given the comparable/worse performance, it’s worth considering whether the decisiveness of majority governments is worth retaining, in the event that crises requiring bold leadership present themselves.

Proportional Representation (STV)

Taking the responsiveness critique of MMP seriously leads to a different approach to proportional representation that incorporates the benefits of ranked ballots. Instead of compensating the vote-share/seat-share difference via the second ballot’s party list, STV systems return to a single ballot and let the voter rank their preferences.

The major move is to change districts from single-member to multi-member. Each race has multiple winners, the chosen number of which dictates the quota a candidate needs to be elected. Gemini lays out the process cleanly here:

Initial Count: First preference votes are tallied for all candidates. Any candidate who reaches or exceeds the quota is declared elected.

Surplus Transfer: If an elected candidate has more votes than the quota (a ‘surplus’), these excess votes are transferred to other candidates. The crucial principle here is that these votes are not wasted; they continue to work to elect representatives according to the voters’ ranked preferences. Different methods exist for determining which specific ballot papers are transferred (e.g., transferring a fraction of each vote, or a random sample of the surplus ballots), but all aim to redistribute the elected candidate’s surplus support proportionally to the next available preferences indicated on those ballots.

Elimination and Transfer: If, after any surplus transfers, no new candidate has reached the quota and seats remain unfilled, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Their votes are then transferred to the next available preference marked on each of their ballot papers.

Iteration: This process of electing candidates who reach the quota, transferring surpluses, or eliminating the lowest-polling candidate and transferring their votes, continues until all seats in the district are filled.

Complexity. Off the bat, the first sin of the system is that it required such a long explanation. It is not intuitive how, if my first-place candidate gets chosen, my remaining rankings get fractionally weighted—but they do.3 This is a serious practical constraint on selling STV to the public, but we shouldn’t consider it a very good criticism.

Sins of AV/IRV and MMP. Previously cited problems, such as non-monotonicity, soupy accountability, and dubious efficacy, all continue to go through for STV.

Weaker parties. There are incentives within STV for candidates to break with their party in order to appeal to the unique preferences of their district. Weaker parties can make it difficult to know who to punish in the government in the next election cycle. Weaker parties also struggle to deal with strong presidents. How much STV leans into niche local interests is positively correlated with the number of seats assigned per district, something that varies widely across different implementations.

The best option? If you do not share my skepticism about coalition governments, nor my worry about weak parties, I’m tempted to say this is the best electoral reform proposal. From the standpoint of gathering a robust preference profile and treating all of those profiles equally, STV succeeds (short of collecting information on preference strength). It achieves proportionality, accepting the accountability difficulties that come with that. There’s a lot going for it in terms of fairness, I just don’t think the outcomes would be better.

Bonus: Expanding the Franchise

Some have argued the right to vote should be extended to children, because various common lines of justifying the scope of the present franchise seem to force that conclusion. This argument goes through: we should expand the franchise. But it’s also an inconsequential matter–Australia and Brazil allowed 16 year olds to vote and experienced no serious shifts in their politics. At the margin it just means progressive parties get a few more votes. If you buy that democratic rights are fundamental and this is a massive ongoing rights violation, concern is warranted, but otherwise4 there are bigger fish to fry.

Bonus: Compulsory Voting

There may or may not be a duty to vote and forcing people to do it with fines is a means of getting that duty fulfilled. Its outcome effect depends on the demographic profile of non-voters being statistically different from voters. Such a difference exists, with non-voters being younger, less educated, and poorer. However, consider that whether someone votes or not is the only information we have about the strength of their preference. Losing that signal of depth of feeling, which candidates have to earn, gives up one form of responsiveness for another.

Compulsory voting doesn’t address voting barriers, for that you want to look to something like voting holidays.

Bonus: Gerrymandering

Though it alienates representatives from their voters’ day-to-day preferences by creating less competitive districts, gerrymandering cancels itself out between Democrats and Republicans at the national level. Fairness critiques probably go through, but reform would do little to alter outcomes. This is hilariously offensive, however:

Bonus: Campaign Finance Reform

“A handful of wealthy donors dominate electoral giving and spending in the United States.” Despite this, elections are shockingly cheap! The total spend on the 2024 presidential and congressional elections came in at just $15.4 billion or $44 per American. So if people revealed they cared (enough to put their money where their mouth is), small dollar donors would have no problem crushing big ones. Assuming people vote for who they think will make them better off by a few percentage points in four years, maybe they could cough up 1% of their yearly income every cycle? The total spend in such a scenario: $237 billion. In reality, 0.065% of annual income goes towards influencing elections–with much of that coming from corporations and unions. Follow the money: most actors in the economy are demonstrating that they don’t think campaign contributions matter.

There are some cool, more esoteric ideas, such as STAR voting, quadratic voting, and Borda count that I didn’t get into here, but maybe in the future we’ll do a follow-up. For a spin on plural voting, check out our post. Hopefully this piece prompted some critical reconsideration of the proposals I did cover. Cheers.

STV is a ranked ballot system, but this section is discussing single-member districts using such ballots.

This is what would intuitively play out in Canada under AV and is why it was Prime Minister Trudeau’s favoured reform. It’s hard to reform a system to hurt yourself.

In complicated elections, computers must be used.

If you are an instrumental democrat, say.

Complicated systems just reward people who care too much about politics.

The purpose of democracy is to throw out the current leaders without bloodshed if average people perceive things as having gotten worse recently. It doesn't necessarily fix anything, but it offers a way out of atrocious failure modes.

WAS UNABLE TO COMMENT SINCE I WAS TILTING AT WINDMILLS. W ARTICLE REFORM SUCKS U GOTTA KEEP DOING SHIT AND PPL ARE NEVER SATISFIED. MIGHT AS WELL KEEP THE CURRENT SYSTEM OF PPL ARE JUST GONNA COMPLAIN ABOUT THE NEXT ONE.