Does Human Nature Matter Morally?

From prudence to principles

There are certain facts that seem to generally be true about people.

Some are psychological. We are risk-averse, willing to take on a disproportionate amount of danger to avoid losses, but tepid when it comes to taking upside bets. Instead of weighing absolute outcomes, we reason from what we currently have. We aren’t good at delayed gratification, overvaluing the present; and we aren’t good at holding things apart from ourselves, overvaluing objects simply because we own them. We like default options more than we would expect and choose differently based on how the options available to us are described.

Some are evolutionary. We are biased towards our kin and find it easier to be altruistic towards them than strangers. We recognize the long-term gains from reciprocity and lean heavily towards cooperation over conflict. The parent that invests more in raising children will be more selective in mating, having more at stake. Those children are expected to quarrel, being competitors for a fixed quantity of parental attention.

Some are genetic. Physically, we get our height, face, and some of our weight from our parents. Cognitively, they give us our intelligence and some of our personality. Psychiatrically, schizophrenia, bipolar, autism, and ADHD are highly heritable, as is Alzheimer’s. A great deal is dictated for us before our number is called.

Many of these are socially and culturally mediated. The low risk tolerance that kept cavemen alive now leaves many fearful of debt. Our reciprocal instincts lead us to save drowning children when we see them, but our parochial altruism makes it hard to muster support for the starving abroad. Even our height is subject, within its preset limits, to the nutritional standards we have the fortune (or misfortune) to enjoy in our youth.

But still, they are components of what we would call human nature. If we were benevolent social planners, these are the sorts of things we would want to know.

Inevitably, when I read about these ideas, I find myself wondering: should facts about human nature bear on our ethics? Can we learn anything about what is right and wrong from examining them?

In one sense they seem immediately relevant–sketch a version of morality and then attempt to apply it to bears. They are not creatures capable of understanding the concepts you are using, and so it is simply an error to do so. We can state this as:

(P1) A creature Y must be capable of understanding X for X to have normative force upon Y.

This seems initially plausible, but there are some easy counter-examples. Pain seems to be something that can generate normative force without being understood conceptually. A bear that attempts to eat a porcupine will soon discover why the other bears tend not to do that! Love can function similarly. Many natural drives take this form.

All of these are examples of prudential normativity–reasons generated on behalf of one’s own self-interest. Bears don’t want to be stuffed full of quills, and that looming consequence exerts normative force upon them. The content of self-interest for humans is grounded in human nature and generally includes the avoidance of pain, the pursuit of loves, and the enjoyment of a good meal.

That’s probably not the sort of morality you had sketched. The principle then, was badly stated. Let’s revise:

(P2) A creature Y must be capable of understanding X for X to have morally normative force upon Y.

Our takeaway from this is that human nature, in giving us conceptual faculties, creates the possibility for us to become moral agents. It generates moral capacity and lays the groundwork for determining who can reasonably be held responsible for following X. However, it so far does nothing to establish the actual normativity of X–why should we care? Why be moral?

Here is one principle we know is absolutely not true:

(P3) If a creature Y is capable of understanding X, then X has morally normative force upon Y.

From the fact you can grasp a morality of subscribing to this newsletter, it does not follow that you have reason to subscribe. We can’t deduce anything about what should be done from facts about human nature, or indeed any facts at all. This is Hume’s Is-Ought gap.

The gap is suggestive of the idea that we should give the inquiry up here, without having discovered anything about moral content (what is moral) or moral bindingness (why be moral). I think that would be premature.

For one, just because we cannot stipulate:

(P4) If human nature is as it is, then human happiness is good.

Does not mean we need to rule out a descriptive principle of the form:

(P5) If human nature is as it is, then Z maximizes human happiness.

This could come in handy. We can work out seemingly morally relevant facts, but they bear on the application of moral content, which we are denied access to. Without that content, P5’s claim about happiness is presently as relevant as:

(P6) If human nature is as it is, then there is no limit to the length nails can grow.

We could collect principles like P5 and work out any number of contingent moralities. Suppose we added the weak premise that happiness is good and the strong premise that we should maximize the good–now human nature has helped specify the application of a rough utilitarianism. Since we have intuitions about plausible moral content, the possibility space for such an exercise is naturally limited.

Intuitions are nice and useful, but sketchy. What if our intuitions differ–how do we adjudicate the winner? Say we both grant that pleasure is good, but you believe a list of higher pleasures (think poetry, film, etc.) is always strictly preferable to other pleasures, whereas I claim we should prefer whatever pleasure maximizes the dopamine neurons firing in the brain.

That’s not a straightforward question, but we can attempt to resolve our moral disagreement like we would other kinds of disagreement. This could mean testing our intuitions in different cases, seeing if they square with other intuitions we agree on, or even examining the source of the intuition to see if one of us has taken a misstep.

All of those methods are made easier by the fact we agreed on the basic claim that pleasure is good. Indeed, most people actually agree with this. But it is hardly alone in the realm of broadly-held intuitions about value. We’ve also got, for example:

Pain is bad

Beauty is good

Knowledge is desirable

Inequality is undesirable

Self-preservation is good

For some, the value of things like knowledge and inequality will decompose further, because they don’t take those to be intrinsically valuable or disvaluable. Knowledge is a vehicle to some more fundamental good, inequality some more fundamental bad. Others will disagree.

Interestingly, the most widely-shared intuitions, about pleasure, pain, beauty, and the value of living, seem as though they are a part of human nature. Hence their universality across time and place. It then follows that part of being human is to value pleasure and disvalue pain.

So P4 is back on the table?

(P4) If human nature is as it is, then human happiness is good.

If what is good is agent-relative and rooted in valuing, then yes, this seems true. Doing that strips ‘good’ of its normativity though. You still won’t be able to get:

(P7) You ought to pursue what is good.

Besides, this is an implausible definition of what is good. We have other intuitions informed by our psychological biases, towards default options, risk averse options, and options involving things we already own. If we run with this, we are going to end up having to accept:

(P8) If human nature is as it is, then human-owned objects are good.

But humans own a multitude of things: drugs, weapons, pelts, dungeons, scalps. Not only have we moved good outside the realm of morality, but we’ve contorted ourselves into making claims we probably don’t believe. Valued = good is an idea best discarded. P4 is off the table. Let’s give up on trying to define what is good.

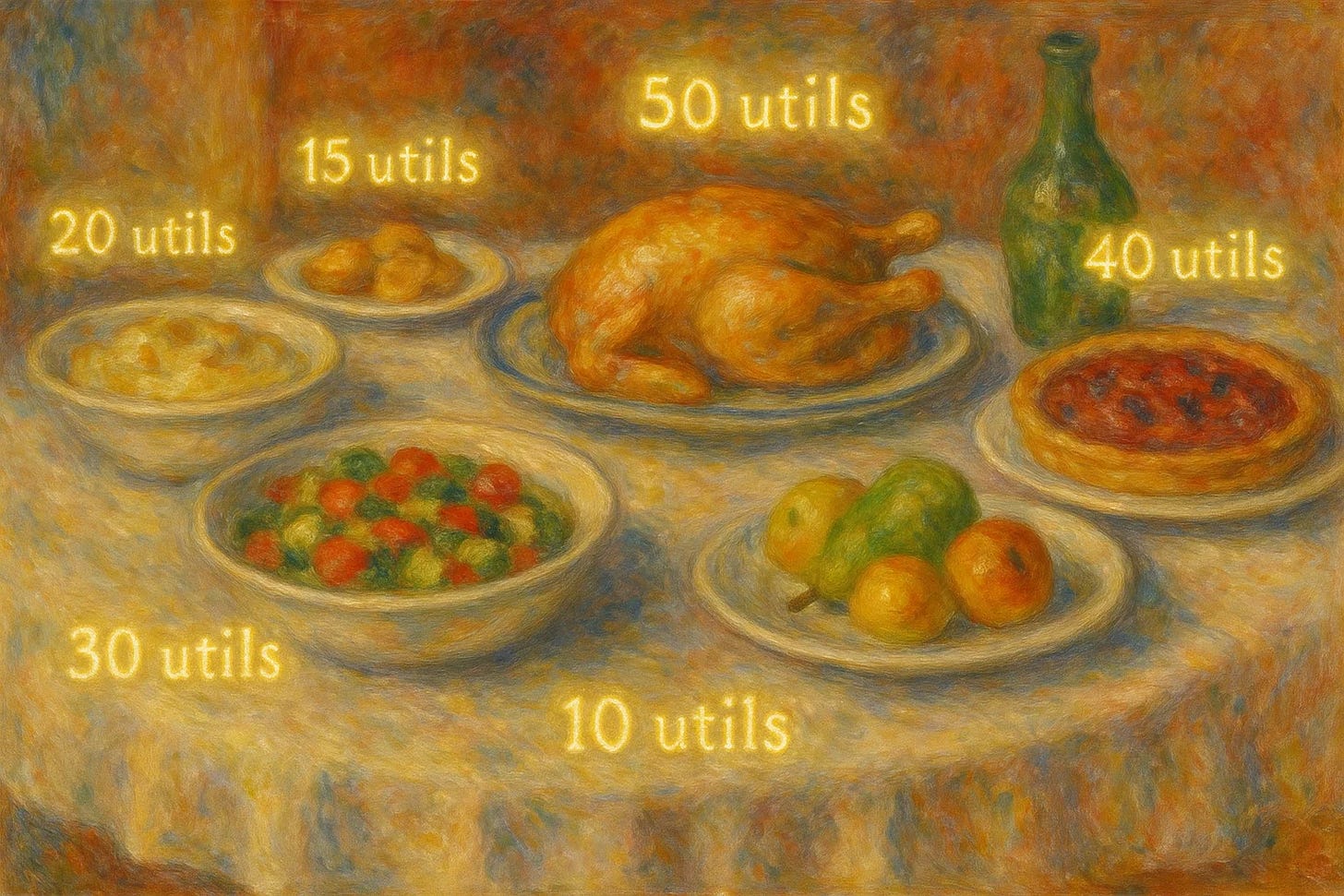

Valuing may not generate goodness, but it does give rise to normative reasons of the prudential sort. This is the kind of reason the bear had not to mess with the porcupine, since it disvalues pain. When economists construct preference-based utility functions and claim not to be making value judgements themselves, this is how they do so.

Earlier, I wrote that this was not typically the sort of morality we have in mind when asked to sketch a system. That’s because prudential reasons are entirely self-centred, in the sense that they arise from what a given agent cares about and are specific to that agent. Moral reasons are centred on right and wrong and have authority over all morally capable agents, regardless of cares. Those who are moved only by prudential reasons we call egoists.

On the face of things, facts about human nature could seemingly ground an entire egoistic ‘morality’. Here it could be objected that this is not a morality at all. If the condition for being one is that its agents act impartially, then it’s going to be ruled out. But let’s not assume that for now.

One attraction here is that prudential reasons have a baked-in solution to the question of moral bindingness, given their source in what the reason-bearer cares about. Why be egoistically moral? Because you already want to.

That’s the core idea that gets played out in an influential reading of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, one of the more well-known works in the history of political philosophy.

Hobbes was a fascinating English thinker who was active at the same time as and was influenced deeply by Galileo. Most know him for breaking with the contemporary consensus around their being a God-given right for kings to rule over man to argue that there was in fact a secular right for kings to rule over men. Yet in his day, he was far more famous for attacking the independent authority of churches, which alienated him from his royalist allies and nearly led to his execution.

He was also a late bloomer, publishing his masterwork Leviathan in 1651 at the age of 63. Amazingly, in 1674, content with his contributions in various scholarly disciplines, he returned to the translating of his youth and completed his very own Iliad and Odyssey aged 86!

Human nature in Leviathan has six key features:

People are simply complicated machines and our mental states are reducible to motions in the brain.1

The overarching desire that people have is to go on living. A great deal of our motivation is said to spring from this self-preservation drive, which comes packaged with a very bleak view of death. This desire isn’t overriding–Hobbes would probably understand preferring death to some large amount of suffering–but it is innate and universal.

Satisfaction of desire is always a temporary, fleeting thing, so people strive for the means to satisfaction and have a capacity to recognize these means. This is the faculty of instrumental rationality.

The majority of desires people have are self-regarding, but altruistic, other-regarding desires do exist. Importantly, if push comes to shove, the self-regarding ones tend to win out.

Differences between people are not so great as to render anyone invulnerable to anyone else. A conspiracy of frail old men could bring down LeBron James, in a way they wouldn’t be able to bring down Thanos.

We aren’t naturally political, contrary to Aristotelian thought, meaning that our states are constructs of our reason, which manifests in a social contract. We create families and small confederacies, but must make deliberate efforts to establish a government with distant strangers.

We can call people with these features members of Homo Hobbes. The first of them might be true or false–I don’t have enough philosophy of mind to hold an opinion. However, I think it’s more a curiosity to ponder than a major premise bearing on the moral theory Hobbes is going to build. The rest, I want to briefly argue, are reasonable based on commonsense observations.

Does everyone want to go on living, as a rule? I think so. Good biological arguments notwithstanding, David Benatar, a philosopher who thinks life is so bad no one should ever have anymore children, describes the literature on subjective wellbeing as finding ‘most people think that their lives go quite well.’2 He thinks people have a number of psychological biases that cause them to believe this fantasy, but he doesn’t dispute that they believe it. For the time being, we are only interested in whether such a pro-existence belief is a feature of human nature, and it seems to be.

Much of life can be chopped up into quests. Elizabeth’s life is briefly absorbed by her romance with Darcy, her heart in Jane’s prospects with Bingley, and her concern in Lydia’s tryst with Mr. Wickham. But all of those dramas come to pass, and after Pride and Prejudice, her discerning mind undoubtedly turnt to other pursuits. So it is with us. No matter how important something is, we are creatures that eventually refigure or move on.

The fourth feature is what makes Homo Hobbes a predominant egoist rather than a psychological egoist. A person that only acted on self-regarding desires could explain all of their acts, in the final analysis, as stemming from a belief that they would benefit themselves. So they might buy their partner flowers, not because that would make them happy, but because they calculated it increases the odds of them sticking around and cooking dinners. This is a universal claim about all acts. To make it more plausible, we can convert it into a claim about precedence, where self-interest predominates over other types of interests, which are given room to exist alongside it. The scope of these other interests tends to encompass friends and family, more than it does, say, the global poor.

Effective altruists and cosmopolitans are familiar with this reality–it’s hard to get people to care about foreign aid. Likewise, it’s hard to get people to not disproportionately care about their inner circle.

Whether we are naturally political is an interesting question. What exactly does Aristotle mean when he argues that people naturally form city states? The idea, I think, is that we have an impulse in our psychology to community build. This gets us to cities small enough to walk across in an hour and not much bigger. That way citizens can know another well enough to participate together in political life.

Conveniently, Aristotle thought that we would naturally form the exact sort of government he lived in during his formative years, given ideal conditions (which were Mediterranean conditions). Social creatures act social. Specifying a form of society as the endpoint of human development though is too strong a claim. 99.9% of people throughout history have lived under alternative arrangements.

If I’m on the right track, Homo Hobbes looks like a pretty good model of human nature for figuring out where a system of prudential action would lead us.

To work out the system, Hobbes rolled out the State of Nature, which abstracts away all existing social constructions and isolates what depends upon a certain element. That input variable is one’s conception of human nature. When thinking this through, we want to adopt a liberal understanding of social construction and exclude any institution that could be explained as having social origins. The family is an example. If it is a component of human nature, as it must be, it will return to the thought exercise via the input. Finally, as its output, the model spits out a prediction of what human behaviour would look like if we reset to a socially blank slate.

Plugging Homo Hobbes into the State of Nature is the main activity of Chapter 13 of Leviathan.

Many have been tempted to interpret the State of Nature populated by Homo Hobbes as a Prisoner’s Dilemma, wherein cooperation between people would lead to a good outcome for everyone involved, but any one person has an incentive to ‘defect’, bettering their position at the expense of everyone else. In the illustration above, if I am Celtics bear and I believe Lakers bear is going to cooperate, I should defect to get all of the honey; if I believe Lakers bear is going to defect, I should also defect to stop him from free-riding. Thus, I always defect, and we end up in the bottom-right scenario.

The point of Prisoner’s Dilemmas is to model individual rationality generating group irrationality, and those who treat the State of Nature this way are attempting to explain why its output is a state of war. As Hobbes puts it, life there ends up nasty, brutish, and short.

Hobbes, not exactly a formal game theorist, told the story like this: people want stuff, but they don’t want to die, and they grasp that anyone could be a threat in that regard. Since fulfilling the desires they have is very important, people seriously consider the first-mover advantage they could enjoy by preempting the actions of others. Enough do this to generate actual violent conflict, and this creates a constant anxiety in everyone that it could happen to them. Life devolves into a fearful mess that stifles flourishing and productive enterprise.

To colour this in, it might be best to picture the desires as the basic goods of a healthy and fulfilling life–food, shelter, sex, water, etc. Some people might want some weird stuff, but the state of war can emerge over our most fundamental needs.

Getting blindsided in Leviathan’s Prisoner’s Dilemma is really bad. There’s a good chance you die. It makes sense to keep your elbows up.

But the structure of the State of Nature is not going to be one playthrough of the Prisoner’s Dilemma; instead it’s more like running it with the same players every single day. When you defect, that gets remembered by everyone else and you develop a reputation as a villain. Bad behaviour against others invites it upon oneself. So the incentive structure shifts from betrayal to cooperation.

There is a countervailing consideration that throws a wrench into all of this. The State of Nature is not a two player game, but a many, many player game. In very large games, it will be difficult to track everyone’s moves, making it possible to free-ride. Returning to our example–now with many bears–the dynamics shift. Each defection at the margin makes it a little more difficult to be a peaceful bear, since more attention needs to be paid to defense. However, there is some threshold defection that will cause the cost of defense to be greater than the gains of harmony. The peaceful bears then conclude that the benefits of cooperation have vanished entirely and they must choose aggression, sending the social order careening into the abyss.

For cooperation to make sense, the benefits from maintaining social order must be stronger than those from free-riding. The reason this leads to an initially ambiguous output from the State of Nature is (1) that the long-term benefits seem to favour the social order, while the short-term benefits favour the free-riders, and (2) that we have not specified the natural trade-off people make between the two time horizons.

Hobbes’ ideas are battling one another on this point. If we want nasty, brutish, and short, we need a strong present-bias. The best case for this existing lies in the strength of our desire for life, which causes us to postpone thought of all else when faced with especially threatening situations. Given the possibility of our destruction at the hands of other people, long-term investment gets thrown out the window and we go in for the state of war.

On the other hand, we previously granted that individual desires are fleeting, and what people really want are the means to satisfy whatever their next set of desires might turn out to be. This gives Homo Hobbes a strong future-looking orientation as a baseline. If the natural tendency to value the future is to be outweighed, either the self-preservation drive is overriding or the State of Nature is one of truly catastrophic risk.

To start with the latter possibility, I don’t believe we should be convinced. The State of Nature, which initially seemed catastrophically risky, loses much of its bite when reframed as an iterated problem. Free-riding might be easy, relatively speaking, when it consists of stealing away public goods, but it’s going to be easy to identify those who defect in the sense Hobbes is worried about. Violence is extremely costly to one’s reputation. It picks you out as the sort of person who cannot be trusted.

Alternatively, we’ve characterized the self-preservation drive as an overarching one that could be limited by strong enough reasons in some other direction. Whether those exist is going to come down to how big the long-term benefits of cooperation are.

As any of us carrying out the State of Nature exercise are doing so from the vantage point of civilization, we happen to know that the benefits are enormous. The fruits of social cooperation built cities, mastered our environment, and sent us to the Moon–all well beyond the reach of other earthly beings. But Homo Hobbes won’t enjoy all of that, being bound to a single human lifespan. Given that, we want to be careful not to overstate the benefits.

Working together will make their days easier, the great generational projects they won’t live to see completed notwithstanding. It would do the same for their family, and also ingratiate them to the community of cooperators.

The way I see it, Homo Hobbes needs to gamble, either on preemptive attack or on cooperating, and the latter poses a higher immediate risk of death. Forming that initial trust relationship is a fraught process. Yet once it’s done, the long-term prospects for self-preservation are much improved, given the need for future gambles has been dissolved. The attacker is going to need to go on attacking intermittently to sustain themselves, risking their person and/or family every time.

Attack is not a free lunch, and the risk gap in the initial choice between cooperation and defection isn’t large enough for the self-preservation drive to kick in and block out consideration of the gamble-free future. For that reason, absent deviant desires to dominate others, cooperation is the natural outcome for Homo Hobbes in the State of Nature.

Contra Hobbes then, we don’t need to create a Leviathan who, by common agreement, is empowered to take any action necessary to preserve the cooperative enterprise. A more plausible state will be one focused on altering the free-rider incentives to keep people in line, be it by policing, better reputation tracking, or some other mechanism.

Now, let’s capture our progress. How does an egoism a la Hobbes do as a moral system?

Moral Capacity - Human nature picks us out as the sorts of creatures capable of ‘downloading’ normative frameworks and applying them to our actions. This makes us capable moral agents. It doesn’t seem to tell us which one we should download or who should get considered in our decisions, leaving our moral patients unspecified. Because desires are natural, including the one to act on them, a self-interest theory where we ought to seek their fulfillment is the normative path of least resistance. The version sketched here requires reasoning about other similarly motivated, cooperation-apt agents, restricting the domain to people, even though animals seem capable of something like egoism.

Moral Bindingness - Insofar as one wants to act on desire, they’re bound by their natural rationality to go along with the dictates of the self-interest theory. They want to be bound.

Moral Content - This part is very much a work-in-progress, but I hope to have shown that the egoist could recognize the potential gains from cooperation with others and work with them in a productive manner. I suspect they would be prospective free-riders and thus have to institute a state to keep each other in-line and working.

We’ve worked out what prudential reasons we might have to act, as well as a system of hypothetical imperatives dictating how to act should we accept those reasons. But is it a morality? I’m not sure. Maybe it’s nothing more than a reassuring description of baseline behaviour. Or maybe there’s something to a project like this, and, with more work, we could specify instructions beyond ‘cooperate’. The jury is still out.

Hobbes was a materialist about everything, even God.

Better Never to Have Been, p. 64

Worthwhile post. I wrote on some similar topics to this from an existential point of view and I come to a similar conclusion to you. Although I would say importantly that human nature has to be relevant to morality because humans have to be assumed to start doing morality. That's important to realize and it means there can never really be an anti-human ethic because ethics can only come from humans, who exactly is total annihilation good to when there are no judges left to judge. The argument that we are just coping about life being good is insane, what objective standard are you measuring life by, the way rocks judge us?