Climate Change Can't Wrong Future People

Rather, it wrongs those now living

The Stakes

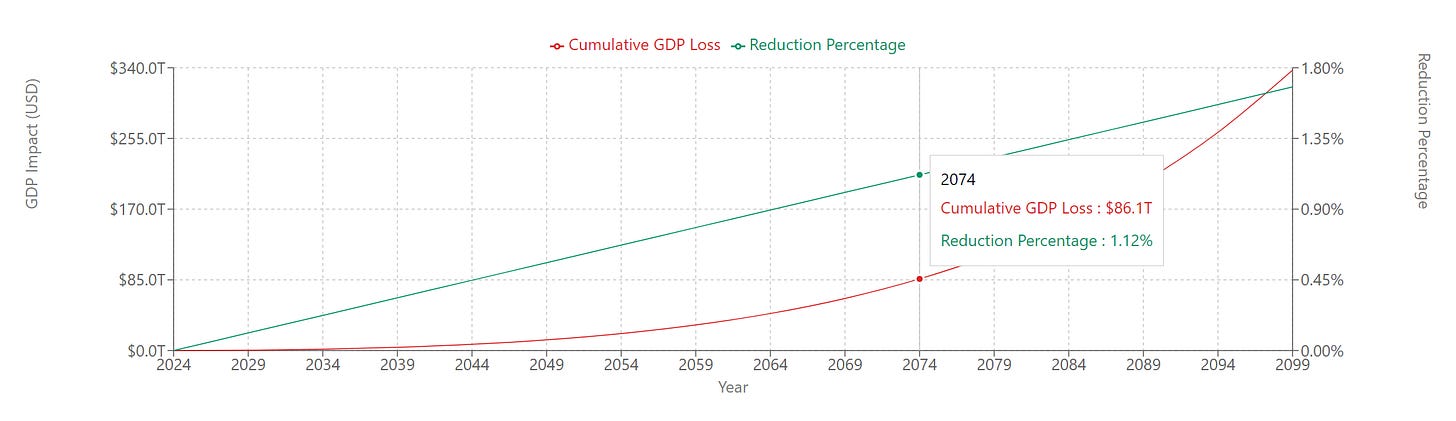

Climate change will be costly. We are unlikely to limit warming this century to below 2°C (3.6°F), with 2.5°C now seen as a more likely figure.1 A recent meta-analysis estimates this would result in a 1.7% reduction in global GDP by 2100.2 If present growth rates hold, global GDP will, by then, be around $1 quadrillion. That’s going to mean a missing $17 trillion in output that year.

In the simplified scenario where the size of the reduction grows linearly, we’d be looking at a missing $365.5 trillion in cumulative global GDP by 2100—3.5x the worldwide output for 2023—that’s bad.

We can acknowledge the badness of such an outcome without succumbing to existential dread. On this timescale, climate change poses no tangible extinction risk.

A recent visualization in the Times set out to show how close the planet is to certain ‘tipping points’, those changes in the natural world that, once inflicted, cannot be undone.3 It seems to me that many extinction arguments zero-in on these events as potential catalysts for ecological collapse. Yet, beyond the aesthetic catastrophe which is the bleaching of our coral reefs, the timelines involved range beyond our lifetimes. Of the melting of Greenland’s ice, the authors write:

Scientists know, from geological evidence, that large parts of Greenland have been ice-free before. They also know that the consequences of another great melt could reverberate worldwide, affecting ocean currents and rainfall down into the tropics and beyond.

When it might happen: Irreversible melting could begin this century and unfold over hundreds, even thousands, of years.

But this raises a very important question: given the distance in time between our actions today and their impacts on these ecological tipping points (which could promote extinction risk), should we care about this aspect of said actions? Should we despair? Do we really feel a moral pull from people in the distant future whose lives won’t coincide with our own?

I.

Set aside all of the people alive today and consider only those who will be born in and around the end of the century. In what way will these people have been wronged (by us) if climate change is not mitigated?

First, we should consider some relevant facts about these people. Though large numbers of them, particularly in vulnerable regions of the world, may be rendered climate refugees,4 or be subjected to increasingly dangerous outdoor temperatures, or fall victim to viruses spilling over from migrating animals, the conditions in which they live will be better than they have been for the vast majority of people throughout history.

Like the vast majority of people who have lived, they would, if asked, report that their lives are worth living. They would feel that things are not bad enough to wish they’d never been born. Research into people living with severe trauma has shown that many still find meaning and a sense of purpose when faced with extraordinarily difficult circumstances; human beings are fundamentally resilient.

This being the case, it would be wrong for us—if it were possible—to tell these people that they should regret their existence. In fact: on most measures of economic wellbeing, these people will probably be vastly better off than the people living today, in 2024.

But can they claim that we wronged them? Could they complain that we did not do more to avert the climate change which, while not ruining their lives, has contributed to circumstances much more challenging than they would otherwise be?

No! Because if we did more to avert climate change, those people born at the end of the century who we have been discussing would never come to exist. Those who enjoyed the gains from aversion would be a different group of people.

II.

Oxford’s Jeff McMahan puts this clearly:5

The changes in policies throughout the world that would be necessary for [averting climate change] would affect, to varying degrees, the lives of virtually everyone now living. The differences in people’s daily lives would mean that different people would meet one another, different romantic partnerships would be formed, and, as a result, different children would be conceived from different genetic materials.

This is an instance of the Non-Identity Problem, canonically formulated by Derek Parfit, which forces us to explain why causing less well-off people to exist when given the choice of better-off people is wrong, given that the choice is worse for no one in particular.

The people in the climate change scenario exist because of climate change. Thus, climate change is not worse for them.

Total utilitarians have no difficulty here, they can plausibly claim that the climate aversion scenario is one in which there is more utility, and thus more goodness, in the world. Therefore, as we should always act to utility-maximize, there is no moral difficulty involved in the choice. However, reasoning about possible lives in this way leads to other, more startling conclusions. These will warrant their own article.

Many of us are not utilitarians. We might believe that the right is distinct from the good and that it is coherent to talk of things like human rights without framing them as the rules which best promote the good.

Holding this belief, we should ask if there is a human right held by the people in the climate change scenario which is violated by our failure to avert the crisis. This could take a positive or negative form: either a right to a minimum level of wellbeing or a right against foreseeable harm. There are good arguments that these are both implausible.

III.

The positive right asserts that people are entitled to be born into a world in which their quality of life is persistently above a certain standard. If this right exists, then parents who knowingly bring children into the world whose quality of life will dip below the standard violate those children’s rights.

But we cannot set this standard at the point where people report that their lives are worth living, for that would be a very low quality of life. The medieval serf, toiling constantly for mere subsistence, doubtless preferred to have lived. Yet the lives of the people in the climate change scenario will be orders of magnitude better than the serf’s. To claim that their rights are violated, the standard will have to be set high enough to where quality of life could realistically drop below that. We’ll necessarily have to be arbitrary on this point, so let’s set it at the average quality of life in 1980. Feel free to imagine it as any other year.

When we do this, we are now supposing that all parents prior to 1980 violated the rights of their children to a minimum level of wellbeing. That doesn’t make sense, unless we accept hideously pessimistic antinatalist arguments.

Perhaps it’s more coherent to vary the quality of life one is entitled to based on the amount of global development that has been achieved? If one’s entitlement is based on the circumstances of the world they are born into, then it is clear that the people in the climate change scenario would only be entitled to a standard appropriate to their damaged world. That is, the entitlement, which has varied upwards as society develops, would simply vary downwards as society declined.

So it seems this positive right cannot get off the ground.

What of the negative right? This is of an easier to grasp sort, akin to the right not to be injured or killed by others. Most people agree that this generally holds. Now consider a case from McMahan:6

Fertility Pill - A couple can have a child only if the woman takes a fertility pill that will unavoidably release a slow-acting poison into the bloodstream of the embryo that will kill the person who will develop from it at the age of 60. They desperately want to have a child and adoption is not an option in their society. So she takes the pill.

Here, without any consent from the child being created, it is completely permissible to act in a way that kills them. This is obvious, since it is the only way for the child to end up living a worthwhile sixty years. McMahan calls this a ‘life-conferring killing’.

But Fertility Pill isn’t truly analogous with the climate policy choice. To really draw out our intuitions there, we should look to his next case:7

Pleasure Pill - There is a pill that greatly enhances the pleasure of sexual intercourse but certain chemicals in it remain in the woman’s body and are then unavoidably introduced into the bloodstream of the embryo if one is conceived, damaging the embryo in a way that is highly likely to cause it to die at the age of 60. A man and a woman each take this pill before having sex, knowing of the likely effects on the child of the woman’s taking it.

Well, here it feels as though wrongdoing may be afoot. We might locate the source of this in the motivations which lead to the child being conceived, as Pleasure Pill seems sapped of the intentionality that characterized Fertility Pill.

We might also locate it in the alternative option available to the couple in Pleasure Pill. In their decision to maximize their own pleasure, they knowingly accept limiting the child’s life to sixty years. They are in no way forced to do this. This mirrors the climate case in structure.

Once again though, the Non-Identity Problem rears its head. Had the couple not taken the pleasure pill and conceived a child without a fixed expiry date, it would be a different child from the one they in fact conceived. The circumstances in Pleasure Pill were necessary for this child to exist with a life worth living. It’s another ‘life-conferring killing’.

On both interpretations, failing to avert climate change would not violate the individual rights of any future people.

IV.

What’s the upshot? Here’s McMahan’s conclusion:8

The [policy] acts that make morally significant contributions to causing climate change also determine who will exist in the future and suffer the bad effects of climate change. Because these people would not have existed had these acts not been done, the acts are not worse for them. The moral objection to these acts is therefore weaker than it would be if the acts would be worse for those people.

What kind of moral objection remains on behalf of the future people? I’m not sure there is one. Perhaps they will look back at our choices and rule that we wronged them by not adequately preserving the things they imbue with impersonal value. These could include the Earth’s biodiversity, its coral reefs, or the flourishing of human civilization across time.

But these are not moral objections, and it won’t be worthwhile to consider them here. Morality is about rightness and wrongness between beings of a certain sort—exactly which being a question for another day—and not about inanimate objects, abstract collectives, or grand impersonal projects.9

If we do not dissolve the Non-Identity Problem—and it is not clear that anyone can10—we should accept the conclusion that there is nothing morally wrong about the effects our chosen climate policies end up having on future people (unless they implausibly contribute to a world in which their lives cease to be worth living).

We might then ask, do present people have a moral objection? Can we claim to be wronged by the changing climate?

V.

Returning to the loss of $365.5 trillion in cumulative global GDP by 2100, we should feel strongly the immediate sense in which this would wrong us. I believe I’m likely to be alive to see the end of the century and that its exceedingly likely many readers will be. These are, in part, our losses.

Before we assess culpability, we might wonder if the solutions available pass a basic cost-benefit analysis. How much would a sufficient ‘green transition’ cost? Barclays, the British bank, cites estimates ranging from ‘$100 to $300 trillion between now and 2050’.11 Much of this would apparently be invested in new infrastructure and energy production. Regardless, these are estimates through 2050 and we have been talking here about 2100. It seems that whatever estimate we accept, we will need to account for an additional fifty years of spending for a fair comparison.

However, the Economist recently argued that such estimates are deeply flawed:12

First, the scenarios being costed tend to involve absurdly speedy (and therefore expensive) emissions cuts. Second, they assume that the population and economy of the world, and especially of developing countries, will grow implausibly rapidly, spurring pell-mell energy consumption. Third, such models also have a record of severely underestimating how quickly the cost of crucial low-carbon technologies such as solar power will fall. Fourth and finally, the estimates disgorged by such modelling tend not to account for the fact that, no matter what, the world will need to invest heavily to expand energy production, be it clean or sooty. Thus the capital expenditure needed to meet the main goal set by the Paris agreement—to keep global warming “well below” 2°C—should not be considered in isolation, but compared with alternative scenarios in which rising demand for energy is met by dirtier fuels.

When one controls for investment that would happen either way, the estimated cost collapses to around $39 trillion total between now and 2100. The article concludes:

In fact, climate change is neither the end of the world nor an expensive hoax. It is a real and difficult problem, but one that can be curbed affordably.

So it seems reasonable to claim that we have economic reason to, in the abstract, avert climate change. Now we should return to the question of who is culpable for these wrongs, as that would reveal who is obligated to right them. Even though each of our individual contributions are imperceptible, I think it must be the case that we are all responsible. Given the extended discussion they’d necessitate, what exactly our individual and societal obligations look like in virtue of that fact and how we ought to handle them are matters best deferred for now.

Conclusion

Back in September, talking about the climate crisis, the president said:13

So many things are on the table. And we can do this—we really can. We owe it to our children. And, quite frankly, we owe it to lead the world.

It makes a lot of sense for older generations to take this tack, most of them have concrete existing relations who they have hopes for and obligations to. But the younger the generation you consider, the more taking action on climate change can also be grounded in the self-interest. We can feel the sense in which we owe it to each other and to ourselves without appealing to our distant descendants, who will, on any plausible model, lead lives worth living regardless of the actions we take today.

Whatever we anticipate the damage from climate change will be, it is clear we should ground our moral reasons for averting it by appealing to effects on presently existing people, not by talk of how bad we may render the distant future.

The vast majority of these would be ‘internal refugees’, moving to more viable regions within their nations-of-origin; https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/climate-migration-101-explainer

Jeff McMahan, "Climate Change, War, and the Non-Identity Problem," Journal of Moral Philosophy 18, no. 2 (2021): 212-213, https://doi.org/10.1163/17455243-1706A002

McMahan, 220.

McMahan, 223.

McMahan, 237-238.

This framing draws loosely on T. M. Scanlon, What We Owe to Each Other (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998), 178-179.

David Boonin, The Non-Identity Problem and the Ethics of Future People (Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2014).

“the aesthetic catastrophe which is the bleaching of our coral reefs” I am less dismissive of the moral worth of non-human life. But even if you think the inherent moral value of non-humans is zero, I would be quite worried (indeed, I am) about messing with the deep levers of the world that control ecological homeostasis. For example, if pollinators go extinct because of climate change, we are screwed, and no recalculations of GNP is going to help.

"Climate Change Can't Wrong Future People"

Exactly. I analogize climate change's effects of future generations as similar to a smoker who leaves a house when he/she dies. The house is worth less money, because the smoker makes all the carpets stink. But the smoker is leaving the house to the future generations. They are not entitled to a house that hasn't been smoked in. They're not even entitled to the house.

https://markbahner.typepad.com/random_thoughts/2014/04/do-people-of-2100-have-a-right-to-be-pretty-angry-about-global-warming.html