Train Bros Are Solving a Pessimization Problem

And a vision for the future

If cars are the most Hayekian technology, then trains are the most Maoist.

Which of these systems is likely to be more efficient depends mainly on the question under which of them we can expect that fuller use will be made of the existing knowledge. And this, in turn, depends on whether we are more likely to succeed in putting at the disposal of a single central authority all the knowledge which ought to be used but which is initially dispersed among many different individuals, or in conveying to the individuals such additional knowledge as they need in order to enable them to fit their plans in with those of others.

Friedrich Hayek ~ The Use of Knowledge in Society

Trains are not only an authoritarian and inefficient medium of transportation, but also an antiquated technology from the 19th century, unbecoming of an ambitious country like the United States. The U.S. needs to look towards new technologies, not marginally better archaic ones.

Before I discuss my vision for the future below, let me ridicule trains for a second discuss the costs and benefits of train centered transportation infrastucture, so you understand why they are not a part of my vision.

Let’s do a fun thought experiment together. Say you wanted to build a new train line. What would that look like?

Step 1) Being a proper and diligent apparatchik, and before undertaking this massive central planning project, you of course have to first ask your city, or group of cities in the case of an inter-city line, to run demand studies. Transit agencies run surveys, traffic counts, and then run some modelling to try to predict where people live, work, and travel. As Hayek rolls around in his grave already, you also to run Title VI (Civil Rights Act) service equity analyses. Are you shifting service or costs onto protected groups? Is there disparate impact? If yes, flag on the play, replay first down!

*Most of the time, Title VI equity analyses just delay or at the most, reroute the line, but sometimes, like in 2010, the government will pull 70 million in funds over Title VI deficiencies, effectively killing things like the Oakland airport line.

**Again, notice what’s happening here from a Hayekian point of view: before a single rider exists, the state has to manufacture knowledge that markets generate automatically!

Step 2) Environmental review. If there’s federal money involved, expect NEPA. State reviews, such as CEQA in California, can add further cost and time. Expect to wait about 2 and a half years for this.

Step 3) You then have to hire and pay for all of the necessary human capital to actually design the train line. Expect this to take 3-5 years on average.

Step 4) We still haven’t even gotten to funding yet. Even if (!) a route makes sense on paper, it only gets built if governments approve funding, which you can guess is not optimized for consumer demands, but instead for political priorities. Politicians may promise to connect certain lines to communities they want support from. Once they lose office, funding for their lines goes with them. Even if they stay in office, political priorities can often shift, and so too the funding, or the federal government doesn’t like something about it, as is the case for that failed Oakland Aiport line.

Even if the funding is consistent, there’s no reason to think steps 1-4 would result in a train line people even want! New York City’s 9 train is a good example of this. The MTA built the 9 train in 1989 to alleviate congestion, but it was already discontinued by 2005. The reason? The system was confusing, induced longer waits, and had little actual benefit.

And if you were wondering: “Average time to complete the steps in the CIG process and receive a construction grant from FTA is 3- 4 years.”

And if you were wondering, yes, it is quite expensive. In New York, for example, it costs billions of dollar per mile to build new subways, and in California, it has cost around 15 billion to even try to build high-speed rail.

Step 5) Then you have to actually build it. This can take anywhere from 5 years to 10 years to, if you’re California, multiple decades.

Step 6) For the sake of completeness, I will add that before you finally run the damn thing, you have to safety test it, which takes about 6 months.

Yes, many of these things can be run at the same time, so in total, expect to wait 10-15 years for a metro line, and 8-15 for an inter-city line.

Okie dokie.

Now let’s do the same thing with cars. You want to get somewhere without a train line, but instead of building a train line, you decide to buy a car.

Step 1) Purchase a car.

Step 2) Drive exactly from the dealership to your destination

Done. Wow that was easy! You don’t need to bring out contrived models to try to estimate demand for destinations, cars are much more sensitive to consumer preferences than that. You don’t need to go through heaps of regulatory add-ons to buy your car. You don’t need to fight with self-interested politicians from the local to federal level, and sometimes cross state (in the case of highspeed rail) for funding to buy the car. Instead of waiting 8-15 years for the new train line, you can wait 18-35 hours for the average car to be built. Even then, you wouldn’t wait that long at all, it’s already pre-built for you. Carmakers build to stock, not to order, because customers value immediate delivery, and carmakers are simply much better at building cars than politicians are at building trains. (most obvious statement I’ve written on the blog so far!)

This is all true for a few reasons. 1) The car market is competitive. Multiple companies, native and international, compete to best satisfy your preferences. This competition brings costs down, and quality and variety up. Innovation is incentivized, and through creative destruction, inefficient car manufacturers are pushed out of the market, and car firms that are better at making people happy are rewarded. The train market on the other hand, is defined not by competition but by monopoly. With no direct competitive threat, politicians pile on goals (equitable hiring, local hiring, union only work, Buy America, climate demands, and so forth), each time and cost-adding. As such, the train market is characterized by slowness, inefficiency, incredible high costs, and, due to a less sensitive demand mechanism, much more dumb decision making. Maoist indeed!

I already mentioned the 9 train example, but another more famous one is the entire history of California high-speed rail projects.

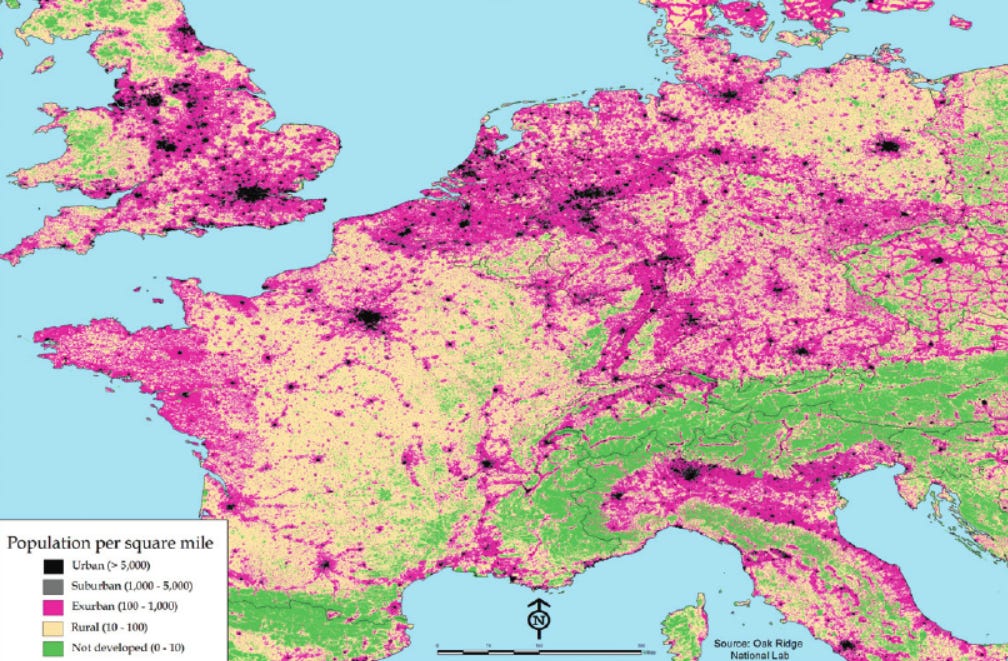

It never made sense. California’s demography is not like Europe or Japan.

That Europe is more densely populated than the U.S., especially western states like California, is a well known fact. I’d like to also include this map because it’s fun.

Successful rail connects multiple dense cities along a corridor. Europe has this, China has this, Japan has this, California does not. What’s in between The Bay and L.A.? Santa Barbara? Bakersfield? The Diablo mountains??? No no no. A quick look at a topographical map explains why this makes such little sense.

California, which is symbolic for the vast majority of the U.S., is not densely populated enough for high speed rail. And yet the perverse incentives of the state government have cost Californians 14 billion and counting. Yes, this is demonstrative of low state capacity, but it’s also demonstrative of what actual consumer demand is for this transit system, which the government has sorely mispriced. Of course, this is also demonstrative of how bad governments are at actually pricing consumer demands. They are much better at fulfilling their ideological objectives. For another example of low state capacity and assymetrical consumer and government interests, check The Washington Post on Biden’s attempt at state constructed broadband networks:

Alex Tabarokk writes that a big part of the problem is the government, as we have seen with trains above, putting on a salad of ideological wish list items.

• “Preference for hiring union workers, who are scarce in some rural areas.

• Requiring providers to prioritize “certain segments of the workforce, such as individuals with past criminal records,” when building broadband networks.

• Requiring eligible entities to “account not only for current [climate-related] risks but also for how the frequency, severity, and nature of these extreme events may plausibly evolve as our climate continues to change over the coming decades.”

I recommend reading Brian Potter’s two-part series on the sad history of American atttempts at high speed rail, but to summarize, an incredibly large amount of US high-speed rail routes have been proposed. These projects have consistently failed because only two lines in the entire world actually pay for themselves, the Paris-Lyon and Tokyo-Osaka lines. High speed rail lines by and large just cannot cover their infastructure and operating costs without government assistance. Given this, high speed rail almost always gets shot down after it spends enough time in the political boxing ring. In the past, there have been too many checks on the power of authoritarian types to build dumb infrastructure projects, thankfully. Hopefully the U.S. does not lose this admiration for efficiency and freedom, as it seems Europe did long ago.

*partial steelman relevent to the last paragraph: Where you have a genuinely dense corridor with stable, repeated demand (Tokyo–Osaka-type situations), the information problem is simpler and the fixed costs can be justified. So I don’t claim trains can never work. My claim is a bit narrower, that in the vast majority of the U.S. and Canada, passenger rail requires planners to solve an information system they are structurally bad at solving compared to the next best car focused option. Even then, as you will see at the end, I think my vision for the future is better than the current Japanese system.

So, to recap, trains, both in cities and across cities, represent a form of transport supply that is incredibly constricted, inefficient, and insensitive to consumer demands. Compared to of course car-based transportation systems.

We can continue to compare the two systems even after the train line is built. Benefits don’t stop just at the pre-construction level. Let’s say the train line was built. Cars are still more sensitive to the preferences of the consumer. First, one of the main problems with trains are how insensitive to consumer preferences they are after they are built. Errors, unlike in flexible private markets, don’t get corrected quickly, if at all. In markets Hayek demonstrates how feedback is granular and constant. In car world, this is obvious. People change routes, live in different places, buy different cars, car firms respond quickly because in markets, the decision maker is tied to the consequences, and so forth. In rail, costs are socialized (so the incentive structure is much weaker), and the rail line is one giant irreversible decision. On the other hand, cars are millions of reversible decisions that update daily.

Which technology is more sensitive to consumer preferences in the long run, do you suppose?

Second, cars are a door-to-door technology; trains are not. This makes them more efficient temporally, and also free of schedule dependence. One of the main criticisms of California’s high-speed rail system, besides the lack of dense intermediate cities, is that, once you get into L.A., or The Bay, you are faced with urban sprawl that is incredibly inefficient to get around through public transport. Even if you get to city center, it would still be much better to have a car on either end. All this to say, I’m not surprised when I read that the data shows commute times for drivers to be on average about 26 minutes one-way, while bus riders averaged about 47 minutes, subway/elevated was 49 minutes, and commuter rail/long-distance was 71 minutes. Those figures include walking and waiting, which is why the differences are so large.

I know what the urbanist types who spend too much time on r/urbanplanning and YouTube videos like this are thinking. “Sure, urban sprawl makes inter-city trains hard to sell. So why don’t we just change the urban sprawl to my preferred dense little ‘15-minute city’ where nobody owns a car, every street is a bike lane, apartments bloom like zoning-approved wildflowers above corner bakeries and matcha cafes, and the only traffic is strollers and San Francisco street cars!” These urbanist types frequently drift policy debates back into their preferred environment of Cities Skylines and Sims, where they can rip all of Manhattan or San Jose up and start from scratch. Obviously, that’s not happening. Urban sprawl should be taken at face value, so the point above about commute times cannot be avoided short of designing a whole new city. (I do have high hopes for California Forever.) What I’m mocking is what Hayek called the pretense of knowledge. Urbanists, being epistemically arrogant, treat the city like a simple algebra problem. It’s true that you can centrally plan a system whose intelligence is distributed across millions of lives, but it will not be as optimized for cost or time as the competing, decentralized system is.

We don’t even need to be theoretical here. We can just look at consumer preferences in history. Try the fruit and vegetable shipping industry on for size. A history of an industry that originated on railroad. Why did railroads lose that business to trucks? Do I even need to answer?

The truck, like cars, are door to door. It’s loaded at the origin and unloaded at the destination, while loads that travel by rail are trucked to the rail, unloaded and reloaded onto the train, shipped onto the train to the destination railhead, unloaded and reloaded into other trucks, and then travel to the final destination. Trucks have more reliable schedules as well, succumbing to delay much less often than trains.

This is why, in the early 1900s, all fruits and vegetables were shipped by iced railway lines, but post-interstate, produce logistics shifted hard to the more time sensitive and flexible truck, and by now, “Trucks ship 83 percent of agricultural products and 92 percent of dairy, fruit, vegetables, and nuts.”

The costs of trains and the benefits of cars/trucks for fruit and people are the same. No wonder the market chose trucks.

We don’t even need metaphors. Screw fruit. Look at the historical foot traffic for cars!

An era of history many people have forgotten (including myself before doing research for this post) was the electric interurban trend of the early 1900s.

Built with the idea of attracting short-distance passenger traffic and light freight, the interurbans were largely constructed in the early 1900s. The rise of the automobile and motor transport caused the industry to decline after World War I, and the depression virtually annihilated the industry by the middle 1930s.

Car adoption crowded out passenger rail long before the U.S. was incentivizing it with the interstate system. In 1928, rail passenger volume was 33 percent lower than it had been in 1920, and automobile registrations topped 21 million. By 1960, rail passenger counts were at 20 percent of 1944 levels, and railroads reported an annual passenger service deficit of $300 million.

Even despite government support of passenger rail through the Post Office, post WW2 ridership still fell. When mail finally going the way of humans and fruit, shifted off trains in 1967, the passenger rail industry cratered, and had to be bought out by the government to create Amtrak.

I encourage the reader, if still skeptical, to just look into the history of passenger rail and cars. It is quite obvious that, even before the interstate system, consumers simply chose cars over trains. And this is what you should want. In a free market, we let the best technology win. That is exactly what happened in the first half of the 20th century.

Earlier this term, I was hanging out with some master’s students in the economics department, waiting for econometrics professor to show up to his office hours. (I am 4th year.) VIA Rail is incredibly expensive in Canada compared to busing or driving, and people were complaining about it. I casually mentioned the main thesis of this post, and one of the master’s students started going on about how actually, we would have lived in what was basically a European-style train utopia if not for Big Oil, which through some vague Tik-Tok or Reddit sourced argument led to the downfall of trains because they were more environmentally efficient. I was quite surprised by a master’s student in economics espousing this kind of conspiratorial thinking. Like really, that’s your preferred, most likely explanation??. I gave him the argument about the history of market simply preferring cars, and he lukewarmly agreed. Jeez though, if eocnomics is this bad, I can only imagine the state of the average sociology masters student, let alone the average person. (although maybe, for many majors, spending years in academia actually reduces the amount of things you have correct beliefs about below the median American).

Now anyway, let’s move on to another perhaps better counter-argument. You might say that the argument of revealed preferences through the market, and the greater success of cars than trains, is just a reflection of government priority. Sure, cars might be more efficient without government support of trains, but if we spent more of our resources on public transport, it would not be more efficient.

Well, state capacity is at an all-time low. If you haven’t already intutited this from the writing above, think about the 3.4 million cases in the Immigration court’s backlog. Think about the mere 322 miles of high-voltage transmission lines built in 2024 (out of the roughly 5,000 miles per year the U.S. needs to ensure grid reliability and cost effectiveness) or the 50% increase in passengers flying since 2000, paired with the complete absence of major airport construction since 2000, and the anemic rate of runway construction.

We need to shrink an inefectual government, not expand it. The government should choose to do a few things quite nicely, and leave the rest to the market. We need to be choosy about what the government can do well, what it will likely fail at, and also what is just plain dumb. With state capacity being this dour, we need to make less dumb decisions. Building marginally better trains in the 21st century, after the 20th already decided that they were an inferior product, is a dumb decision.

My Vision

Supersonic planes and autonomous vehicles should dominate future transportation networks. Urbanist types hate automonous vehicles even though they solve a lot of their problems because it’s hard to get out of old habits. Matthew Yglesias succinctly sums up the situation in this note:

“I get that it’s inconvenient for those of us with strong urbanist priors that self-driving technology solves a lot of our favorite problems without adopting our favorite solutions. But that’s life.”

Using supersonic planes and autonomous vehicles, the average person should be able to get from any point in the country to any other point in the country in about 3 hours, door to door, cost-effectively.

We should have supersonic airplanes made by Blake Scholl’s Boom Supersonic and other competitors. An autonomous vehicle should be available to pick you up within 30 seconds and whisk you to a nearby airport. They should be able to travel at 100 or more mph since they’re better than human drivers. Security at the airport should be instant, (Dulles Airport level, an example of high state capacity which I experienced earlier this year, wowing me and showing airport security can be incredibly quick even post 9/11) Because the automonous vehicle is so fast, if your trip doesn’t require a plane, it should be able to get you there very quickly. Of course, if it does require a plane, because it’s supersonic, it will be able to get you from SF to NY in about 3 hours or less. If you want to travel to London from NYC, you should be able to get there in about 3 and a half hours.

In cities, automomous cars and autonomous buses with dynamic route planning based on riders’ actual needs will beat subways’ 1-dimensional tracks every time, and because the’re autonomous, run on solar, and organized by AI bureaucrats, they will not only be more efficiently run but be essentially free.

As I said in the beginning, trains are unbecoming of the ambitious and innovative country that I aspire to see. Abundance and Up-Wing types, and of course the curious people looking in from the door, should be looking at and beyond the technological frontier, not romanticizing financially irresponsible and antiquated 20th-century technology.

![California population density [600 x 600] : r/MapPorn California population density [600 x 600] : r/MapPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!S_D6!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F31eabb91-ec6d-4a4b-b849-52c1a7daf48f_600x600.png)