Evolution Strikes Back

I'm sure you opened Substack to read a comedic platonic dialogue about evolutionary philosophy, right?

This is part 2 of an earlier post. Read that first or you’ll be confused. Or you could just read this o3 summary, I guess…

“I read your post.” said a cloaked man behind steel bars.

I woke up halfway, thinking I’d heard something.

“Yeah, you. I read your post on Substack. The one about evolutionary morality. I saw you were in the jailhouse.”

“Oh, so you read it till the end! Then-”

“It was shit. You strawmanned my entire profession.”

He pulled the cloak back to reveal a thin, balding man wearing a checkered sweater and a bow tie.

“I am a moral philosopher, and you have wronged my entire discipline with your amateurish, unoriginal, silly writing style.”

“Oh screw off. I wasn’t trying to write formal philosophy.”

He stood there, expecting more from the interaction.

“Go away! I’m tired, and no one will pay my bail for punching that person in a wheelchair. I assume that’s not what you’re here to do.”

“What?”

“Pay my bail.”

“Certainly not.”

“Then what are you doing here!? It’s dawn on a Thursday. Don’t you have work to do?”

“I thought I told you I was a professor.”

An inmate’s cough interrupted a long silence.

“Well, I guess I have nothing better to do. Let’s duke it out.”

I slowly got up from my concrete bed and sat on the bench.

“Good good. Firstly, humans are the only moral agents. Animals aren’t moral agents, since to be one necessitates consciousness. That error poisons your entire analysis.”

“I disagree. I think it’s highly anthropocentric to assign moral beliefs to only humans. Just because bacteria sense danger with chemoreceptors instead of eyes and ears, and they move away from it with their flagellum instead of a musculoskeletal system, does not mean they are not moral. It is simply a difference of physiology. Detection of threat, so internal signalling, so coordinated physical evasion. Running away from a tiger or swimming away from acid, it’s the same.

The Homo sapiens system is astronomically more complex because it has to coordinate trillions of cells to move a large, heavy body, but its underlying purpose and operational flow are a direct, unbroken evolutionary inheritance from its single-celled ancestors.

And the reason I call this moral is because it reveals preferences! If I see a human run away from a tiger that’s trying to eat them, it is fair to assume that they find dying to be painful, and it does not like painful things, (moral claim), so it runs away. How are bacteria different here?”

“You’re anthropomorphizing bacteria. They don’t think something is wrong, they just go off instinct. You need to be conscious to be a moral agent!”

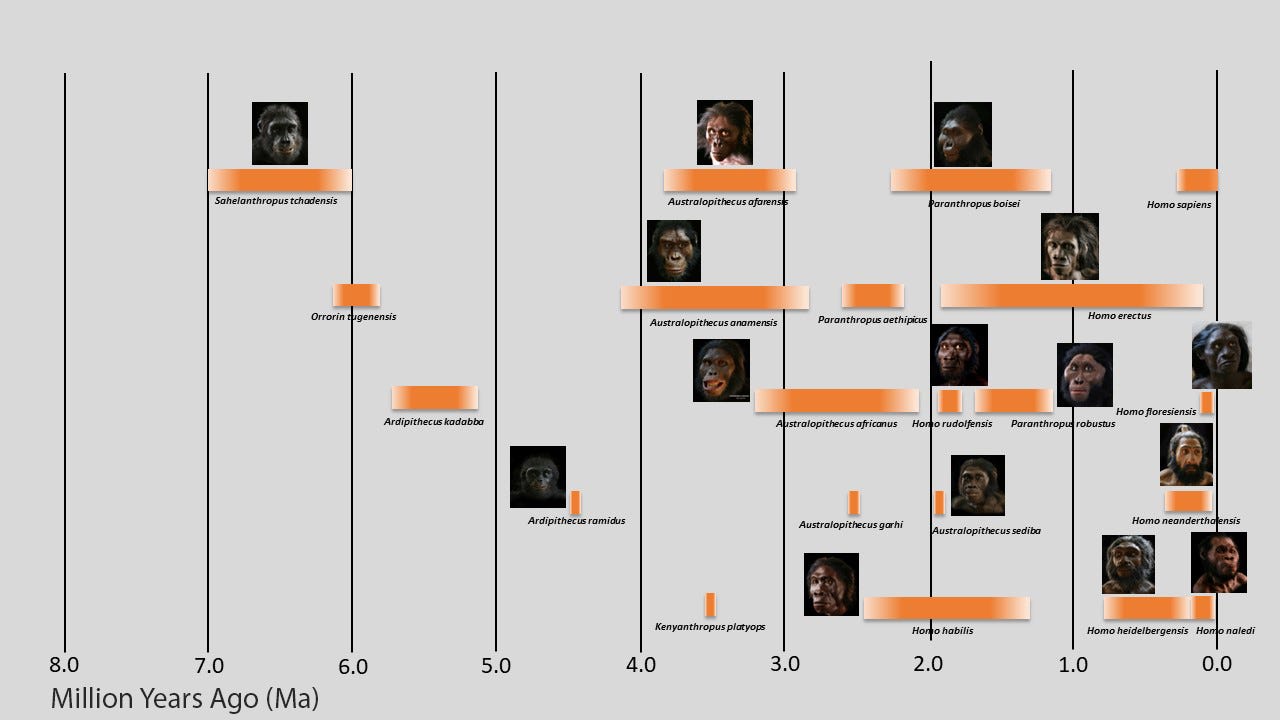

“Fine. Perhaps bacteria are not moral agents. But what about Neanderthals? Homo Erectus? The Denisovans? Modern Chimps? Dolphins?”

“I would have to know more. I want a few things. A concept of good and bad, a sense of ought or should, and self-awareness.”

“But I’m trying to demonstrate to you that this is a continuous problem. You are trying to force categories onto a continuum of intelligence and self-awareness. When will you grant moral actions to an animal? What is the line? Humans have often drawn these arbitrary lines in the past to secure our differentiated status in the animal kingdom, and it usually ends up being dumb in retrospect.

But fine. I won’t quibble over definitions. Besides, it’s actually irrelevant for my argument, since I postulated intelligent snakes and bees, not as they are now. So they would have you satisfied.”

“I forgot to mention empathy. Moral agents require understanding how their actions affect others. Psychopaths aren’t capable of morality. Snakes are psychopaths.”

“The mothers would evolve some sort of empathy, as it’s necessary for reproduction. Again, much less than us, but it’s a continuum of empathy that has marginal effects on moral behaviour.”

“That phrase. I don’t like it either. 'Moral behaviour' is an empirical domain. We can have normative discourse about the correct moral beliefs without reference to observed behaviour. My colleagues and I do it all the time. Indeed, that’s how you find moral truth. So I’m not sure how 'moral behaviour' is different from action, broadly construed, nor why an evolutionary story about the source of our action would have implications for moral philosophy.”

“Because as intelligent as the average moral philosopher is, I do not believe that intuitions have no effect on them. That’s why I say that moral philosophers do not argue for moral truths in a vacuum. All moral theorizing starts from intuitive data. If the reliability of that data is in question, so is any structure we build on top of it.”

“Doesn’t this resign you to deep skepticism of other fields too? Perhaps you trust expert hunters and teachers, but not quantum physicists? What good are our intuitions in the quantum realm compared to the forest?

“That’s the difference. Our intuitions are terribly misaligned when it comes to quantum physics or even Einstein’s theory of relativity, because we evolved in a kind of middle world. That’s why it’s so hard for people to understand them. The difference, and why I trust the conclusions of physicists more than moral philosophers, is that the structures they are building on top of our intuitions are more mathematical. That gives it a level of rigour that moral philosophy does not have, and it also means it falls prey to our evolutionary biases less often, because more math = more crowding out of intuitions.”

“So you’re saying that our biological heritage has done a good job keeping us away from moral truth?”

“Probabilistically speaking, yes. Evolution luckily giving us mostly true moral beliefs would be a cosmic coincidence, if you agree that evolution wasn’t selecting for moral truth, but gene propagation.”

“Yes, I grant that. I also grant that it shapes our intuitions to a large degree. But I don’t grant that it affects moral truth. Sure, physics uses more math, and that’s a leg up on us, but I still see environmental changes in philosophy over short periods of time, which signals non-evolutionary influences. Our moral intuitions, if passed down to us by biology, should roughly match those handed down to the Mesopotamians several thousand years ago. They don't. What we find in Gilgamesh or the Iliad are entirely different ways of thinking about moral matters. You may contest that we have made moral progress, but there is no denying moral change.”

“Interesting. I don’t know if I’m convinced that this disproves my thesis. Remember the musical scale analogy. It’s not that evolution predicts moral beliefs, but that evolution provides the raw material we form our beliefs out of, by emphasizing or deemphasizing certain adaptive traits. Pain aversion, reciprocity, kin loyalty, dominance ranking, purity/disgust, empathy, fairness, out-group wariness, and prestige hunger. Depending on the ancestral situation, each one can boost reproductive pay-off more than others. Moral progress, then, is simply the continued rearranging of traits that were adaptive in the African Savanna. For example, blacks in Compton in the 80s emphasized out-group bias for obvious reasons, western Europeans in the same decade deemphasized it for equally obvious reasons.

Bronze age city-states were at constant war. In that way, they were more like Compton. (sorry I’ve been listening to NWA a lot recently) Loyalty, honour, respect for dominance, and so forth are more emphasized for practical reasons. Universal empathy predictably stays low.

There are genetic reasons for you to put a high probability on my argument. Corey Fincher and others have a classic cross national study on the effect pathogen prevalence on human moral behaviour. High pathogen load reliably predicts tighter, in-group-focused norms, whereas low pathogen load predicts looser, more universalistic fairness (bigger moral circle!)

“The regional prevalence of pathogens has a strong positive correlation with cultural indicators of collectivism and a strong negative correlation with individualism. The correlations remain significant even when controlling for potential confounding variables. These results help to explain the origin of a paradigmatic cross-cultural difference, and reveal previously undocumented consequences of pathogenic diseases on the variable nature of human societies.”

Part of the reason (not all) that we have a larger moral circle today is because we have a cleaner society where people don’t have to worry about disease as much when interacting with others.

The organization of societies seems to have large effects on morality, then. This reorganization is usually a second-order effect from technological innovation. Technology was of course was in play with pathogen reduction, but also in shifting moral attitudes towards individualism with the printing press, or towards sexual empowerment and equality with the contraceptive pill. Or social media now, with it’s cancel culture digital reputation concerns shifting moral behaviour once again.

Of course, none of this is really reinventing the wheel of morality. As the environment shifts, (technology changes) certain adaptive traits are de or reemphasized. And often we have competing moral opinions, because contradiction was often best 100,000 years ago.

Leaders saved lives in war or famine, so copying them was a cheap risk-reduction. (The conservative says “deference to hierarchy is good!) But blind obedience could doom a hunt or let a tyrant skim resources, so smart foragers kept private mental models and sometimes split the camp. (The American Revolution was a good thing, not a bad thing!) And of course, while everyone has these competing ideas in their mind, mutations in the gene pool will cause some to have more then others, or cause them to react differently to technological changes, which is part of the reason for our species’ philosophical and moral disagreements.

The printing press emphasizes individual reasoning at the expense of deference to authority, because it reduces the information advantage that priests had. But it’s not as if individuality was suddenly made out of whole cloth. It was simply a reorganization of previously adaptive traits due to an environmental change.

Again, competing ideas: Microbe risk and zero antibiotics 100,000 years ago made out group bias a solid heuristic.

Yet sharing information with distant bands boosted gene/idea flow. And we also had cascading levels of empathy within bands due to genetic links.

Emphasize the ladder and the expense of the former while reducing pathogen risk, and you have a wider moral circle, and liberal norms of trade and immigration. Disgust and xenophobia go down!! (but not completely, again, evidence of a genetic link)

Do I even have to go through this rigmarole with social media cancelling and status signalling??”

“Interesting. Please condense that into a single argument.”

“My bad. Let me put this in your language.

Okay, Premise 1: Humans everywhere inherit the same small set of social behaviours (pain avoidance, reciprocity, kin loyalty, dominance, purity, empathy, fairness, out-group vigilance, prestige hunger). Although these seem sensible, they are actually a highly arbitrary grouping based on what happened to be adaptive in our evolutionary history, and could have easily been radically different if selection pressures were different.

Premise 2 is that technology/societal reorganization (usually caused by tech though) changes which behaviours boost survival/reproduction (antibiotics cut pathogen risk, the Pill cuts paternity risk, printing cuts information asymmetry, smartphones increase reputation signals).

Premise 3: Moral codes shift by amplifying the now-cheap traits and muting the now-costly ones. No society adds a brand-new circuit (nobody valorises maximizing random suffering or kin-betrayal. Likewise, even the most universalist creed retains tribal reflexes (us vs. Nazis, us vs. republicans). The moral imagination roams, but always inside the walls evolution built.

So historical moral change—from Bronze-Age war to liberal human rights, doesn’t refute my evolutionary agenda-setting argument, it seems to make more credible my theory that the same hardware is constantly reemphasized as the environment changes, thus incentivizing different traits.”

“But we are still so different from Mesopotamia or Greece. Yes you will say that every known society valorizes some combo of care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity, and even loyalty to kin, honor-based status, and revenge justice, which are of course present in Gilgamesh and the Iliad are also present today, even if modern institutions channel them differently (court systems replace blood-feuds). But I find it highly reductionist to conclude that morality has not changed very much because of a few abstract concepts.”

“As I said in my post, I don’t think that evolution causes all moral change. Morality will drift over time, my evolutionary account predicts this, because the environment is not static, and philosophical argument has a part to play.

But to repeat, the probability of our morality being ‘correct’ erodes proportionally by the fraction of its inputs caused by evolution. And it seems that you have now granted that it is a fraction, and possibly a quite large one. It seems to me that most of the technology and philosophical argumentation is operating in a space demarcated by what was adaptive for a very specific species in a very specific time and place. As far as Mesopotamia goes, sure, they didn’t preach universal human rights, but they did punish freeloaders, honour kin bonds, think pleasure was good and pain was bad, fear ritual impurity, and for the most part shared similar views on fair trade.

Does it surprise you that those core instincts are common across time and space? It doesn’t for me. They’re exactly what I’d expect from a primate species that needed cooperation to survive. So anyway it seems that cultural evolution has stretched the ‘fairness’ and ‘care’ modules to wider circles, but it hasn’t invented new moral emotions. It’s almost all just variation within rigid infrastructure.”

“I see. I had a feeling you would talk about those traits. Things like kin bias and empathy are still kicking and are obviously adaptive. So, moral beliefs which draw upon them are based upon Darwinian pressures, not resemblance to the moral truth, yes, yes.”

He clasped his hands together and looked out my toaster-sized window pane. It was dawn now.

“I agree that these have survived and are the basis for some of our morally-relevant intuitions. However, is it an incredible coincidence that these would track moral truth?

Attempting to abstract away all facts about ourselves (beyond being entities that do things) and asking what morality is, what are we left with? The domain of right and wrong. Good and bad things to do. This could relate to self-regarding action or other-regarding action. Speaking about the latter, we're talking about a relational concept. Is it really all that shocking that empathy (the ability to situate oneself within other standpoints in a relationship) would help us grasp truths about it, if they exist? If moral truths are facts about how interacting agents should treat one another, it is entirely expected that the social intuitions that allow us to think about these interactions would be relevant to figuring out the truths.

Through the process of moral reasoning, we turn this relevant but flawed intuitional material into the normative theories we have today. Notably, some of the material is less useful than others. Keep in mind, we toss plenty of our intuitions into the trash upon reflection in other areas. Look at all the counter-intuitive things we've figured out in probability theory, for instance.”

“Okay, so Sharon Street phrases it like this:

Either you have the truth tracking account: Natural selection favoured hominins who happened to latch onto the independent moral truths (because doing so boosted fitness).

or,

The adaptive-link account: Selection favoured hominins whose evaluative attitudes simply forged useful links between circumstances and action, so no need for the attitudes to be true at all.

You’re talking about empathy. I grant that it probably is necessary, or at least highly useful for figuring out what is right and wrong. Useful, but perhaps other moral intuitions are not. Obviously we have in-group bias and identifiable victim bias, for example.

Now, you might retort that most of our morality is universalist and tries to correct for these, proving moral progress can be detached. But what I’m trying to prove is not that these heuristics are inescapable, but that they are evidence of an animal that evolved as a fitness-optimizer, not a truth-detector. Yes, empathy gives us a capacity to think through social relations and right and wrong concepts, yet our brains can still spit out wildly distorted judgments from the standpoint of objective morality (if such a standpoint exists).

If evolution weighted the heuristic deck toward partiality and parochial fairness, the reflective equilibrium we reach will still lean that way, just with better arguments.

You mention probability, but that’s similar to my physics example. In probability, we have external reality (dice rolls, data) to show our intuitions are wrong. Morality, unlike physics or probability theory, lacks as much of a calibration target. It relies more on intuition.

So yeah intuitions can be refined; I don’t doubt that has occurred, especially recently. But you owe us a story about why fitness-tracking should correlate with truth-tracking better than chance. Pointing to the possibility of refinement doesn’t by itself supply that correlation. Perhaps it supplies some of it. Most likely it does.

But then we are back where we started. Evolution has an influence, which increases the ‘coincidence problem’ Street talks about.”

“You’re underrating ethics’ rigour. Moral philosophy focuses on constructing and evaluating arguments based on reason and evidence. Even if a certain philosopher fails to do this, they exist, like in the physics field, in a highly competitive and scrutinizing environment, where you can trust others will make light of your logical mistakes. It’s not just people throwing intuitions around. C’mon, these are serious and incredibly intelligent people all over the world who have committed their entire lives to it, over generations!”

“I understand it seemed like I was underrating it, but I just can’t agree that physics and ethics have the same level of rigour. Logic can guarantee validity for sure, but I’m not so sure about truth.

Yes philosophers can prove theorems if their assumptions are rock-solid. But in moral theory, the starting assumptions are themselves moral intuitions, no? It seems that we have gained the ability to make incredibly internally coherent arguments inside of a sandbox evolution created.

I also don’t see philosophers converging on truths the same way physicists have. Of course there is much disagreement in physics, but professional philosophers split nearly 50 / 50 on moral realism vs. anti-realism and scatter across utilitarian, deontic, contractualist, virtue-ethical camps, and even more I can’t name in one paragraph. Add to that that non-professionals heavily disagree on facts about morality, whereas non-professionals rarely disagree on facts about physics. I mean c’mon, decades of debate on trolley problems, animal ethics, future-people, etc. keep ending in stalemates! Doctors are on average healthier than most, but ethicists are not any more ethical than the average.

Isn’t persistent expert dissensus, at least compared to physics or biology or chemistry, exactly what you’d predict if everyone is still tugged by subtly different evolutionary priors, and exactly what you wouldn’t predict if pure rigour reliably zeroed them out?

I’ll also add Jonathan Haidt’s work for fun, which showed that moral judgments flash up in about 200ms and the conscious arguments arrive later as post-hoc justifications. Of course professional philosophers will try to correct for this; will do better then others, but still, it should up your probability of my argument. Which is that elegant proofs are still built off, for the most part, adaptive intuitions.”

We heard a loud bang on the door. A fat cop with a tomato face was yelling through the glass. “Open up you god damn hippies! Unlock this door right now!!”

“Oh dear. It seems I’m running out of time. Ugh, I don’t think I’ll unlock it just yet officer! Give me a second.”

He turned to me, and his lips curled at the edges. “Table that part for a second. Enough about evolution. Let me give you a hypothetical!”

“Okay, imagine that you’re walking down the street, yes, and suddenly, you see someone trying to eat a car!”

He was standing on his tippy toes he was so excited. We were in his wheelhouse now.

“The person wants to eat the car. It’s going to be quite painful, but, oh well, they want to eat it. What is your first reaction?”

He stared at me intently, like a child asking if they can stay up late.

“Do you think it’s rational? Unreasonable? Would you tell them to stop??

Oh, c’mon, say something!!”

“Why are you asking me this?”

“Just answer!”

“Let me in now!!” The officer roared.

“Fine! I would probably say to stop. It’s dumb as hell.”

“Aha!! I got you! If morality is really not objective, then all that matters is moral stances. But you just admitted that it was bad to eat the car, even though it was their stance that told them to do it! So there’s something else, some eternally true thing that stops you from thinking it’s rational to eat the car. It’s probably that suffering is universally bad. Not just today, or tomorrow, or according to me but not someone else, no, it is always bad because it is a universal truth. And you thinking it’s irrational to eat the car, even if he wants to, shows that you believe there is some eternal moral truth like ‘Pain is bad and always bad.’”

“Nah. You had me for a moment there, but the answer is obvious. It is rational to eat the car! Let me explain. Even more common-sense claim: You should execute the goals you want to execute, and vice versa. So in this way, it’s intuitive to eat the car.”

“But at first, you didn’t think that. And most people wouldn’t. I bet you only did because you want to keep your anti-realist position. I even bet you still think it’s irrational, that something in your gut tells you so. And that makes anti-realism less likely to be true.”

“But evolution strikes again! It’s intuitive to think it’s rational because pain avoidance is hard-wired through evolution. But when you think about it cool-headedly, it’s obvious that it’s rational for people to do what they want to do. Our intuitions are just misplaced because not causing severe pain to yourself has been in our evolutionary history since the beginning.”

“But it’s still deeply unintuitive. Doesn’t that reduce the probability of you being right?”

“No, because as I wrote in the post, evolution doesn’t track moral truth. Trust your intuitions when it comes to assessing the danger of jumping off a cliff, pissing your girlfriend off, or counting the number of leaves on a branch. Those were all adaptive for survival. Moral truth wasn’t a variable that evolution cares about, and so our intuitions should not be trusted on the subject. The fact that the car example is unintuitive is irrelevent then!”

Suddenly the door came crashing down. The officer had taken a battering ram out of a storage closet.

The recently slimmed-down cop (thanks to Ozempic) trampled in and fell on the floor, exhausted.

“You’re, huh, damn. You’re going straight, straight to jail, god damn it.” He stood up, his hands on his knees, looking at the concrete. “Just let me catch my breath, and, huh, god damn! Just let me and then I’ll arrest you. Hold up a sec.”

“No officer, you don’t understand, I broke into the jailhouse for a valiant cause, the defence of moral realism!”

He sprang up like a grasshopper, and looked him right in the eye. “Oh. Wait a minute, are you hear to argue about that new Outrageous Fortune piece?

“Yes. I thought it was terrible.”

“Me too! I read it at my break and threw my coffee across the room!”

“Well, a fellow realist! My luck-”

“Hold your horses buddy. I’m actually a species-dependent moral realist. I think we might be able to avoid a lot of the worries here if we simply don't assume that any set of objective moral rules is species-independent.

For instance, what if we posit that there indeed exists one 'set' of true moral claims, and resulting moral duties, but they vary by species. Some claims included in the set might then be: It is wrong for humans to murder, or, it is fine for snakes to kill other snakes in these contexts...

But still insisting there is only one unified set of moral truths, just that the set extends differently to each species. In that case, finding 'objective' human morality will involve dealing with matters (human experience) that are fairly imminent, and not with matters we can have little certainty of.”

I shrugged my shoulders, thinking it over. My companion was not so pleased.

“Unprecedented confusion I’m witnessing here. Next to me is a subjectivist who’s never read a single anti-subjectivist argument in his life, and now I’m faced with a radical subjectivist cosplaying as a realist.

You’re no realist at all!

If intelligent snakes and intelligent homo sapiens existed at the same time, I bet a million to one you would be repulsed by snakes killing each other, and think it wrong or irrational at least.”

“But those institutions are not reliabl-”

“You’ve said enough, part-time blogger. Anyways, not only is that unintuitive, you also make the claim that “if human, then ____”. Rather, it should be “If person, then ____”. Human or snake or bee is a non-morally-relevant category. Person is. And if snakes are intelligent, then they should be considered persons. Most moral realists would agree that they are bound by the same set of moral propositions. Where have I gone wrong, officer?”

“Well first off, you broke into a jailhouse at four in the morning-”

“Eh, sorry officer, but I kinda agree with bowtie here. It seems subjective to categorize morality by species. It seems like humans try to overlay categorizations onto continuous problems again. Of course we have definitions for what makes something a species or not, but there will always be slight mutations in the gene pool, and some species that can mate but not produce viable offspring, some species that can do it half the time, and so forth. By your standard, shouldn’t species get slightly different morality, even if they are fairly similar, like donkeys and horses?

How about even more specific: There are slight mutations within all species. Should people get slightly different morality based on marginally different genetic mutations?

What even is the median for each species here? It just seems that once morality is keyed to any biological discriminator, tiny intra-species differences threaten to splinter the ‘true morality’ into N moralities.

It also feels like it doesn't give enough room for philosophical argumentation, just giving free passes based on evolutionary instinct. Indexing duties to species biology makes normative reasoning kinda redundant; argument can never overturn a built-in instinct. Also, because we evolved out group bias, does that make it okay? And what even gets included in the set seems arbitrary. Why include empathy but not out-group bias in the objective set? What's the criterion for each species’ objective facts? All of their adaptive traits? Just some? How do we decide?”

The officer was more then pissed off now, and began handcuffing the professor.

“Get your hands off me, you phony realist! This is a violation of the categorical imperative!”

“Buddy, right now your imperative is to face the wall.”

“But, but you need a principled rule for why some evolved propensities are facts and others are not! Hey! Don’t touch me there. Oh! I’ve never witnessed someone so uncouth…”

“Can you just be arrested in peace? God you’re hard to get along with.” I said.

“Oh I can be worse. You should check out the RateMyProfessor comments.”

“Shut up and get in your cell you self-satisfied nerd.” He locked it and threw the key in his pocket.

“But you don’t understand! Without a criterion, your view collapses into ad-hoc moral taste. In other words, subjectivism! So you might as well go punch a lady in a wheel chair too!”

He slammed the door shut.

“Well, don’t actually, for the sake of her utils” he whispered to himself.

A few minutes passed by. I heard the philosopher muttering something.

“Evolution wrote our moral firmware; philosophers keep pretending they coded it from scratch. If our moral hardware evolved to keep small bands alive, betting it just so happened to target universal truth is like assuming a smoke detector doubles as a saxophone, possible, but the music will probably stink.”

“What are you talking about? Do you agree with me all of a sudden?”

“No. I’m thinking about writing a Platonic dialogue where I make you lose the argument. I was just rehearsing your part.”

“Good good. Firstly, humans are the only moral agents. Animals aren’t moral agents, since to be one necessitates consciousness. That error poisons your entire analysis.”

This is too quick, I don't know who would endorse this. Using consciousness as the standard, the philosopher is willing to grant all kinds of creatures agency which they clearly do not have. Agency is a capability claim, at minimum predicated upon those able to reason among alternatives. To be plausible, I think a language capable of communicating mutual expectations is also necessary.

You have the philosopher go on to expound upon this consciousness requirement, but it gets off on the wrong foot. The fact that action reflects some measure of biologically instilled prudence is not going to get the doer of that action to moral agency on its own.

« You should execute the goals you want to execute, and vice versa »

what do you mean by should?