A Friend of the Future

Book Review: Steve Jobs

Tyler Cowen considers the post-1973 era to be one of Great Stagnation. Peter Thiel is fond of saying that innovation has stagnated in the world of atoms, but quickened in the world of bits, with the chief cause being differential government regulation. But when Erik Torenberg is spelling out the Thiel Manifesto, he can’t help but include a glaring exception to his catchy one-liner:

“We've had this narrow cone of progress around the world of bits—around software & IT — but not atoms. The iPhones that distract us from our environment also distract us from how strangely old & unchanged our current environment is. If you were to be in any room in 1973, everything would look the same except for our phones.” — “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

Peter Thiel misses the days when technological progress was not just about new software, but building underwater cities, ending death, or travelling to other planets on space ships.

In this era of atomic stagnation, and fixation on software (represented by Microsoft and then Google), Steve Jobs was the exception to the rule. A man who believed that only the integration of software and hardware, or, as Thiel would say, the union of bits and atoms, could yield great products.

This philosophy put him squarely on one side of what would be the biggest divide in the technological community of the last 70 years: Open vs closed. The hacker ethos, favoured by Microsoft and later Android, preferred the open approach. Bill Gates was a smart pragmatist who knew that licensing Microsoft’s operating system, from IBM to panhandlers, would be best for Microsoft’s market share.

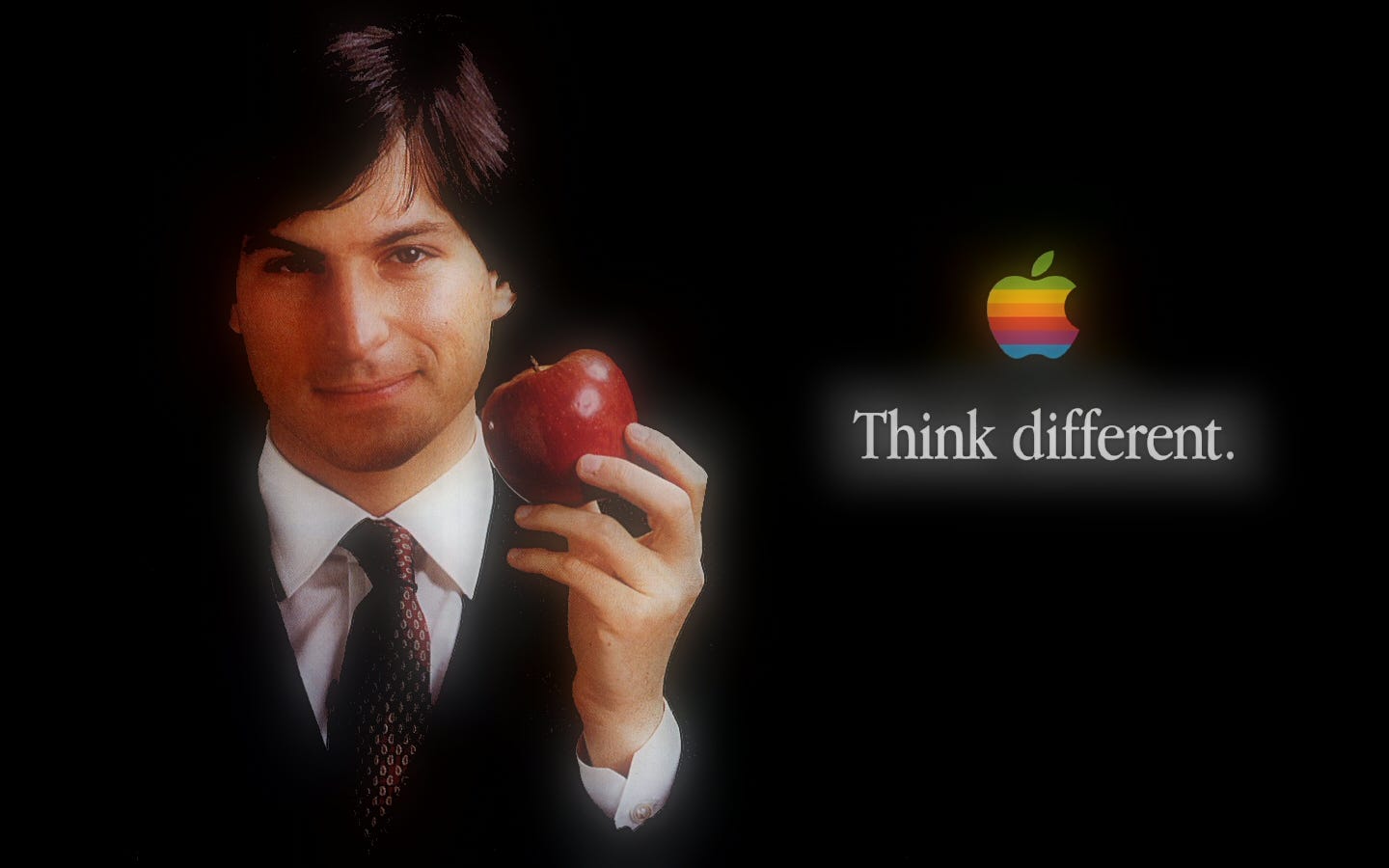

But Steve Jobs was able to think differently: He was a perfectionist, and great artists do not compromise.

Unlike Gates, Jobs had a completely different philosophy.

My passion has been to build an enduring company where people were motivated to make great products. Everything else was secondary. Sure, it was great to make a profit, because that was what allowed you to make great products. But the products, not the profits, were the motivation.

That is the voice of an artist first, and a businessman second. Sophisticated, simple pieces of art, were what Jobs desired. And the only way to achieve that is the complete integration of software, hardware, and content into one single, perfectly designed bundle of atoms and bits. “Jobs is a strong-willed, elitist artist who doesn’t want his creations mutated inauspiciously by unworthy programmers.” Explained ZDNet’s editor Dan Farber. “It would be as if someone added some brush strokes to a Picasso painting or changed the lyrics to a Dylan song.”

Jobs created products that were beautiful but not always market dominating. Indeed, by the late 1980s, his approach seemed almost quixotic, his products beautiful losers, seemed to have lost the battle, as Apple faltered while Microsoft pulled ahead. Offices across the world were using IBM PC’s running Gates’s software, not Apple Macs running Jobs’s. By this point, Jobs was over at Pixar, and although he looked back fondly at the days of the Macintosh’s triumph, he was done with Apple.

What he didn’t know was that he had a future in the company he had made, that the war of open vs closed had campaigns to be waged, battles to be won.

By 2011, he had achieved his impossible heroic comeback. When in 2011, he stepped down from the company he had started in his parents’ garage, Apple had become the world’s most valuable company. And the reason? As Jobs put it:

“Only a company that owns the whole widget— the hardware, the software and the operating system,” can “take full responsibility for the user experience. We can do things that the other guys can’t do.”

Things, things like

This is a book review chiefly about innovation. At a time when we finally seem to be freeing ourselves from the Great Stagnation, where some Democrats are even inviting the Abundance movement into their ranks, degrowthers, or as James Pethokoukis would say, down-wingers, still remain far from defeated. Humanity is being given another chance, to embrace solar and nuclear technology, to build our societies around AI, to create a better species with biotechnology, to revolutionize the world of atoms with robotics. We must not squander this opportunity.

In this chaotic, revolutionary moment, one needs to choose sides. There is a bright, dynamic future, and there is a dark one too. A future that is zero-sum, one populated by risk-averse Malthusianites who fight over thinner and thinner slices of a stagnant and lethargic pie they call a civilization. How will those people look back on the regulators? The risk-averse? The unadventurous? The leech cultivators? The anti-prometheans? Will it be as friends, or as foes? How will they look back upon those who create abundance? Excitement? Invention? Or as Thiel would say, those who go from zero to one.

Those who think different.

Will they look back upon them fondly? Will they look back at us, like we look back at Bell, Tesla, Edison, Watt, and the Wright brothers?

Hopefully, it is obvious to you that you want to be a friend of the future, not an enemy. But one might ask, how do you become a friend?

Well,

Who better to learn from than Steve Jobs?

In no way is this book review a lionization of anybody. Well, it is a bit…

Here’s me trying not to be: Jobs is a man honeycombed with contradictions, one who is not as neat and pure as his products. One should not take away that he was perfect from this book review. I focus on the upsides because the theme of this blog is innovation. But of course he made terrible mistakes along the way, and could have done many things in more ‘considerate’ ways. So with Jobs, do not swallow the whole pill. One should, as with all people, pick around their food, savouring the best and leaving the rest on the table.

Jobs was both a commune living hippie tripping on LSD, and a tech billionaire who launched the most successful, disruptive product in history. He was a visionary who saw the promise in the miracle of digital animation, and the son of a mechanical engineer riding his bike around the suburbs.

He could be a complete Lennon-like asshole, and a sensitive man prone to publicaly crying, a Zen Buddhist, and a tantrum thrower, an orphan, but a neglectful father.

Reading Isaacson’s biography illuminates the multi-dimensionality of Steve Jobs. He’s a human who rejects categorization and invites reconsideration. The whole book is a challenge to preconcieved notions.

The substack community has various preconceived notions. One is the value of reason. Here is Jobs on the topic after visiting India for a year:

"Coming back to America was, for me, much more of a cultural shock than going to India. The people in the Indian countryside don’t use their intellect like we do; they use their intuition instead, and their intuition is far more developed than in the rest of the world. Intuition is a very powerful thing—more powerful than intellect, in my opinion. That’s had a big impact on my work.

Western rational thought is not an innate human characteristic; it is learned and is the great achievement of Western civilization. In the villages of India, they never learned it. They learned something else, which is in some ways just as valuable, but in other ways is not. That’s the power of intuition and experiential wisdom.

Coming back after seven months in Indian villages, I saw the craziness of the Western world as well as its capacity for rational thought. If you just sit and observe, you will see how restless your mind is. If you try to calm it, it only makes it worse, but over time it does calm, and when it does, there’s room to hear more subtle things—that’s when your intuition starts to blossom and you start to see things more clearly and be in the present more. Your mind just slows down, and you see a tremendous expanse in the moment. You see so much more than you could see before. It’s a discipline; you have to practice it.

Zen has been a deep influence in my life ever since. At one point I was thinking about going to Japan and trying to get into the Eihei-ji monastery, but my spiritual advisor urged me to stay here. He said there is nothing over there that isn’t here, and he was correct. I learned the truth of the Zen saying that if you are willing to travel around the world to meet a teacher, one will appear next door."

Jobs’ use of intuition was his secret to success.

There are two things at play here. First is obvious, the taste, the artistic bend. That is what allowed him to design great products. The 2nd is the reality distortion field.

But I’m getting carried away. You’re wondering what I meant by reality distortion field. And perhaps you’d even like a story, one to exemplify all these awesome qualities I’m talking about. But there are so many…

He revolutionized the music industry in the 2000s, first with the iPod, and then iTunes. Not only did that save the music industry from the existential threat of illegal downloading, but for the first time in history, people could walk around with 1000 songs in their pocket. And Jobs’ vision made this a reality.

Maybe I could tell that story. Or maybe I could tell the story of his time at Pixar. Jobs bought an unprofitable company that was mostly focused on hardware, and repeatedly wrote checks for it out of his own pocket when it neared bankruptcy, all because he saw its potential to revolutionize the animation industry. Although he bought it because of its hardware, his intuition led him towards its small creative department, which was simply used to demo their hardware. Jobs saw promise, and even when Disney executives tried to shut it down, he kept Toy Story going with his own funding. His bet, purely on intuition, paid off, as you’ll see it usually does. Pixar created the first-ever full-length computer-animated feature film. This opened the floodgates for the computer animation industry.

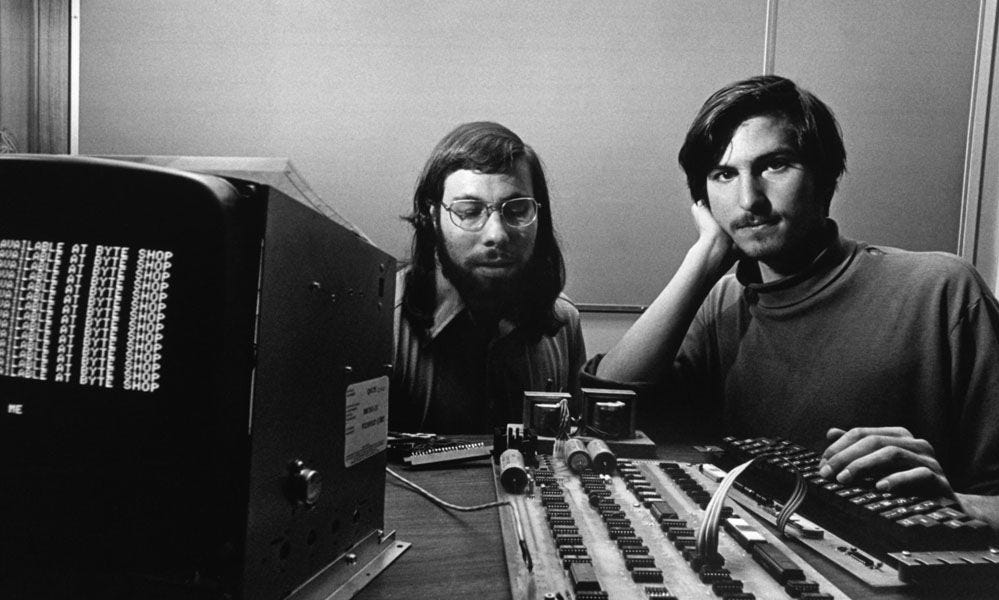

Or I could talk about the iPhone. Or Jobs and Wozniak’s initial development of the first Apple computer, which kick-started the home computing industry.

But I don’t think I will. My favourite episode in Jobs’ life is the 1980 -1984 period, where he takes a small group of swashbuckling California engineers, musicians, and poets, and revolutionizes the home computing industry. All of these stories will give you a taste of his brilliance, but I’ll choose this one today. For the others, you’ll just have to read the book.

Painting a personality

Let me give you just a bit of context before the story of the Macintosh.

Early on, Jobs realized he was a forceful, confident person. When he was 12, he wanted to build a frequency counter but lacked the parts. So he called Bill Hewlett (the CEO of HP) to ask for spare parts. He got the parts, and a summer job too.

When he was 19, he wanted to make some money. He saw an ad for the video game manufacturer Atari in the newspaper. So he walked straight into the lobby, a fresh college dropout in sandals. He smelled like BO because he insisted he didn’t need to shower on a frutarian diet. He told the personnel director flat he wouldn’t leave until he was given a job.

Jobs became one of the first 50 employees of Atari.

So here we have this young little Nietzschean overman, who does well for himself but drives around without a license plate, parks in handicapped spots, and freaks out at waiters when the food isn’t to his exacting standards. All’s to say he’s benefiting himself much more than the world. But then something interesting happens.

Jobs realized he could impart his confidence onto others and thus push them to do things they hadn’t thought possible. Secondly, acting like rules and reality don’t apply to you can wind you up as an asshole, but it can also mean you think you can do the impossible, and sometimes if you think you can, you do.

In the summer of 1975, a guy named Nolan Bushnell got the idea for a single-player version of Pong, where someone would volley the ball into a wall that lost a brick whenever it was hit. He came to Jobs and asked him to design it. He would get a bonus for every chip fewer than fifty that he used. Jobs recruited Wozniak, and together they embarked on the game.

The catch was that Jobs demanded it be done in 4 days. Bushnell never would have demanded this, it was self-imposed because Jobs needed to get to a commune in Oregon in time for an apple harvest. (a side gig)

Wozniak replied that it was an impossible request. There was simply no way he could do it in four.

Yet in the end: “A game like this might take most engineers a few months,” Wozniak recalled. “I thought that there was no way I could do it, but Steve made me sure that I could”. So he didn’t sleep for 4 nights in a row and got it done. And astonishingly, only used 45 chips.

And this brings us to the reality distortion field. It was there that Steve first learned it. If you pretend you’re in complete control, people will assume that you are.

As Wozniak later recounted: “His reality distortion is when he has an illogical vision of the future, such as telling me that I could design the Breakout game in just a few days. You realize that it can’t be true, but he somehow makes it true.”

You can see Steve Jobs is shaping up to be much more then an asshole hippie. But the journey has only begun. Let’s get to the story.

Xerox: steal or fumble?

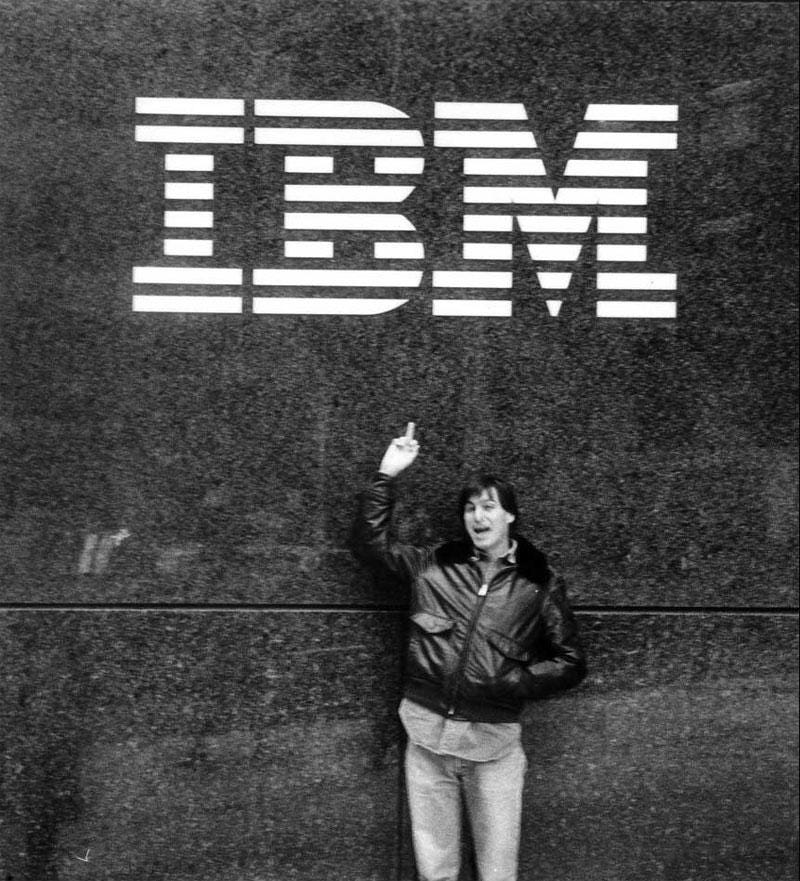

Steve Jobs is already slightly famous for his work with Wozniak on the Apple and Apple 2, but by 1979, IBM is beginning to beat Apple, and Jobs feels the urgency.

So he makes a deal with a rival computer company in the bay, one named Xerox, in the summer of 1979. Xerox was to invest a million dollars in Apple, which by the time Apple went public a year later, was worth 17.6 million. In return, it agreed to show Apple a new, groundbreaking technology, although almost nobody in Xerox knew how groundbreaking it truly was.

There are two main players at Xerox in this story. Adele Goldberg, who understood, like Jobs, the goldmine Xerox was sitting on, and Larry Tesler, a Xerox scientist who was naively excited to show off his innovative work after his bosses back east had routinely failed to appreciate it.

The first meeting went Goldberg’s way. Jobs and a few A team members from Apple were ushered into the lobby, and shown a very controlled demo of a few applications, mostly a word processor. Of course, Jobs got on the phone, called the Xerox headquarters back east, and started berating them for shorting him on the deal.

So he was invited back a few days later. This time Jobs brought some more top dogs from Apple, including Bill Atkinson, his maverick engineer that used to work at Xerox, and knew exactly what to look for.

When they arrived in the lobby, one of Goldberg’s engineers was trying and failing to keep them entertained with more displays of the word processor. Jobs at one point yelled “Let’s stop this bullshit!”. So the engineers huddled together and decided to let larry Tesler open the computer a bit more, but only the unclassified parts, such as the programming language, would be shown to Jobs, they assured Goldberg.

They were wrong. Atkinson had read their papers. He knew they were only getting a taste. Jobs again phoned the head of Xerox to complain, and a call immediately came back from some old dusty corporate headquarters in Connecticut. To Goldberg’s horror, the group of bigwigs who had never been in the loop on the future of technology, yet controlled Xerox, had decreed that Jobs and his group be shown everything. Goldberg stormed out in rage.

Tesler finally pulled back the curtain. Atkinson stared so closely at the individual pixels on the screen that Tesler could feel his breath on his neck. Jobs was hopping around like a bunny. “You’re sitting on a goldmine” He shouted. “I can’t believe Xerox is not taking advantage of this”.

The amazing feature was the graphical user interface that was made possible by using a bitmapped screen. No more were the old 70s computers with neon green numbers. “It was like a veil being lifted from my eyes,” Jobs recalled. “I could see what the future of computing was destined to be.”

Was this stealing? Or was it more of a fumble? It’s important to differentiate between invention and innovation here. Between new ideas and execution. There is a lot of truth to both assessments, but Jobs and his engineers significantly improved the graphical interface ideas they saw at Xerox that day. And they were able to implement it in ways Xerox never could.

For example, the Xerox mouse cost 300 dollars, and didn’t roll around smoothly. So a few days after the visit, Jobs went to a local firm in the Bay Area and demanded they make him a simple, 15-dollar, single-button mouse that he could roll around on his blue jeans. The firm complied.

And there are the concepts. The mouse at Xerox couldn’t drag around windows. Apple’s engineers devised an interface so that you could not only drag windows and files around you, but you could even drop them into folders. And Jobs spurred them daily to improve the “desktop” concept by adding delightful icons and menus like little trash bins and double clicks for folder openings.

Jobs had a passion for smoothness. He wanted the mouse to smoothly scroll through files, not lurch. That would not be Zen. He also wanted the mouse to move in every direction, not just up and down. This required a ball, not wheels. One of the engineers told Atkinson there was no way to build such a mouse commercially. Atkinson walked into office the next day to find out Jobs had fired that engineer. His replacement was waiting for Atkinson. “I can build the mouse”. He said.

It’s not like Xerox didn’t try to capitalize on what they had. And in doing so, revealed the importance of execution. In 1981, they introduced the Xerox star, well before Apple released the Macintosh, that had the graphical interface. But it took minutes to save a large file, it cost 16,000 dollars, and was aimed at the networked office market. It flopped.

Jobs took his team down to the retail store, but deemed it so worthless that he told his employees not to even buy one. “We knew they hadn’t done it right, and we could, at a fraction of the price”.

A few weeks later he called Larry Tesler and told him “Everything you’ve ever done in your life is shit, so why don’t you come work for me?”

He did.

But by 1982 Apple had still not produced a computer with a graphical interface. The computer, which they thought would have it, The Lisa, had been bogged down in administrative difficulties caused by Jobs’ tempestuous personality. So Apple administration forced him out of Lisa, and relegated him to a small development project in a distant building that could keep Jobs occupied and away from the campus. Not much had come of it so far, so they gave Jobs total freedom.

That development project had been called The Macintosh.

You Say You Want A Revolution

Like Robert Oppenheimer, one of Jobs exceptional qualities lay in his ability to identify, organize, and direct highly talented people in the right direction.

One day he appeared at the cubicle of Andy Hertzfeld, a young engineer. “Are you any good?” It was the first thing he said. “We only want really good people working on the Mac, and I’m not sure you’re good enough.” Hertzfeld said “Yes, I’m pretty good.” Jobs came back later that afternoon, peering over his cubicle. “You’re working on the Mac team now. Come with me.” He replied that he needed a couple more days to finish the Apple 2 product he was in the middle of. “You’re just wasting your time with that!” Jobs replied. “The Apple 2 will be dead in a few years. The Macintosh is the future of Apple, and you’re going to start now!” He yanked the power cord to Hertzfeld’s Apple 2, causing the code to vanish. They drove over to the office and he plopped him in his new desk that day.

Jobs was building a merry band of pirates. Rebellious, passionate, hippie types. People at the intersection of liberal arts and technology. In interviews, he would cover a prototype of the Mac in cloth, dramatically unveil it, and watch their eyes. If they lit up and they said “Wow!”, he recruited them. He would ask interview questions like “How old were you when you lost your virginity?”, “How many times have you taken LSD?” Some uptight engineers from the east would get red and squirm in their chairs, and Jobs would laugh away.

Once hired, Jobs was good at manipulating his team into doing unimaginable feats. Fueled by his bang-on intuition, he directed the team in the right directions, his distorted reality enough to get them to their destinations in record time.

But it wasn’t just that he could impart confidence through thinking impossible things were possible. He was also good at manipulation. He knew when someone was faking it or truly got it, he could sting a victim in a perfectly aimed emotional gut shot, or flatter someone so much that they desire his approval above all else.

“He had the uncanny capacity to know exactly what your weak point is, know what will make you feel small, to make you cringe,” Joanna Hoffman said. “It’s a common trait in people who are charismatic and know how to manipulate people. Knowing that he can crush you makes you feel weakened and eager for his approval, so then he can elevate you and put you on a pedestal and own you.”

In 1983, when Apple was in need of a new president, Jobs, in his search for one, developed a specific attachment to a man by the name of John Sculley. He was president of Pepsi at the time, and his Pepsi Challenge campaign had been an advertising triumph. The Apple team wanted him, and so did Jobs. So Jobs tried to charm and persuade him into leaving Pepsi for Apple.

In one now-famous, climactic moment, Sculley and Jobs stood atop a rooftop in Manhattan, discussing the change. Sculley had been indecisive, going back and forth between NYC and Cupertino. He offered one last demurral, a suggestion that maybe Jobs and he could just be friends, and he could offer Jobs advice from the sidelines. “Anytime you’re in New York, I’d love to spend time with you.” Sculley recounted the dramatic moment:

“Steve’s head dropped as he stared at his feet. After a weighty, uncomfortable pause, he issued a challenge that would haunt me for days. ‘Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water, or do you want a chance to change the world?’”

It was one of Jobs’ well-timed gut punches. He had practiced how to do them many times over the years. The stare he gave Sculley, unblinking, had also been practiced alone with a mirror ever since he learned it from a friend in college.

“He had an uncanny ability to always get what he wanted, to size up a person and know exactly what to say to reach a person,” Sculley recalled. “I realized for the first time in four months that I couldn’t say no.”

Do I even have to say whether he became president?

Over in the Macintosh division, Jobs began building a team of strong people. Those that crumpled under his personality were fired or quit, and week by week the Macintosh team began to take more of the form of Jobs’ own personality: It was a group of renegades. Intelligent, brutally honest, and very tough.

One day Jobs barged into a cubicle of one of Atkinson’s engineers and gave the Steve Jobs usual: “This is shit.”

But unlike many, the guy said, ‘No, it’s not, it’s actually the best way,’ and he explained to Steve the engineering trade-offs he’d made. Jobs backed down. He respected those who could stand up to him, because only those who weren’t faking it had the power to do so.

But eventually that same engineer found an even better way to perform the function that Jobs had criticized. “He did it better because Steve had challenged him,” said Atkinson, “which shows you can push back on him but should also listen, for he’s usually right.”

In an important paragraph, Isaacson shows the upside of Jobs’ tempestuous personality:

Jobs’s prickly behavior was partly driven by his perfectionism and his impatience with those who made compromises in order to get a product out on time and on budget. “He could not make trade-offs well,” said Atkinson. “If someone didn’t care to make their product perfect, they were a bozo.” At the West Coast Computer Faire in April 1981, for example, Adam Osborne released the first truly portable personal computer. It was not great—it had a five-inch screen and not much memory—but it worked well enough. As Osborne famously declared, “Adequacy is sufficient. All else is superfluous.” Jobs found that approach to be morally appalling, and he spent days making fun of Osborne. “This guy just doesn’t get it,” Jobs repeatedly railed as he wandered the Apple corridors. “He’s not making art, he’s making shit.”

Another anecdote I love was when Jobs came into the cubicle of an engineer named Larry Kenyon. (he would frequently just barge in and start asking questions) Larry was working on the Macintosh operating system. Jobs complained that it was taking too long to boot up. Larry tried to explain, but Jobs cut him off. “If it could save a person’s life, would you find a way to shave ten seconds off the boot time?” he asked. He begrudgingly admitted he probably could. But this wasn’t just a hypothetical.

Jobs suddenly went to a whiteboard and demonstrated that if there were five million people using the Mac, and it took ten seconds extra to turn it on every day, that added up to three hundred million or so hours per year that people would save, which was the equivalent of at least one hundred lifetimes saved per year.

“Larry was suitably impressed, and a few weeks later he came back and it booted up twenty-eight seconds faster,” Atkinson recalled. “Steve had a way of motivating by looking at the bigger picture.”

The result was not just a tough, smart team, but one that shared Jobs' commitment to making a great product, not just a profitable one. “Jobs thought of himself as an artist, and he encouraged the design team to think of ourselves that way too”. Said Hertzfeld. “We said to ourselves, ‘Hey, if we’re going to make things in our lives, we might as well make them beautiful’”.

Was his abusive behaviour worth it? Maybe, maybe not. Isaacson leans on not. “There were other ways to have motivated his team.” He wrote. He certainly brutalized many feelings. But it can be incredibly inspiring.

As Jobs recalled, “By expecting them to do great things, you can get them to do great things. The original Mac tam taught me that A players like to work together, and they don’t like if you tolerate B player work. Ask any member of that Mac team. They will tell you it was worth the pain.”

According to Isaacson’s interviews, most did. “He would shout at a meeting, ‘you asshole!', you never do anything right,’” Debi Coleman recalled. “It was like an hourly occurrence. Yet I consider myself the absolute luckiest person in the world to have worked with him.”

Design

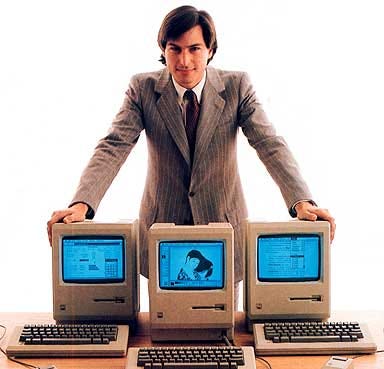

The Macintosh hasn’t come out yet. In fact, it’s far behind schedule, thanks to Jobs’ perfectionism. Part of the reason is his obsession with aesthetics, something that would come to define Apple’s brand identity.

Inspired by Japanese Zen Buddhism and the Bauhaus style, Jobs developed a minimalist philosophy of clean and simple technology. “I have always found Buddhism, Japanese Zen Buddhism in particular, to be aesthetically sublime.” He said.

He repeatedly emphasized that Apple’s products would be clean and simple. “We will make them bright and pure and honest about being high-tech, rather than a heavy industrial look of black, black, black, black, like Sony,” he preached. “So that’s our approach. Very simple, and we’re really shooting for Museum of Modern Art quality.” Apple’s design mantra would remain the one featured on its first brochure: “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

He leveraged the simplicity of a desktop. People intuitively knew how to move papers around. They knew that the one clipped on top was the most important. Jobs knew computers were still a mystery to most Americans, so Jobs made the design of Apple computers, and later groundbreaking products in years to come, as intuitively obvious as possible.

Jobs didn’t want the Macintosh to feel too masculine, too overbearing. It had to be inviting to the user, especially one who had never used one before. So he plopped down a phone book on the table in one of his meetings with his engineers, and declared that the computer shouldn’t have a footprint larger than that. The engineers complained that it was impossible. Usually, the engineers made the product, and the designers worked around that. At Apple, it was usually the reverse.

Preliminary designs made with plaster would be made. Other engineers would say it looked cute, and Jobs would go on a tirade of insults. Another would be developed, and another, until the by the fourth attempt Jobs was critical of details others could not even perceive.

Jobs kept insisting it looked friendly, so it eventually came to resemble a human face. It had a larger “chin” at the bottom, and a thin bevel or “forehead” at the top.

One day Atkinson came into the office full of energy. He had just figured out how to code circles and ovals onto the screen. He did a demo, and everyone was impressed besides Jobs. “Well, circles and ovals are good,” he said, “but how about drawing rectangles with rounded corners?”

Atkinson replied that it was unnecessary, and also probably impossible. Jobs jumped up and exclaimed “But rounded corners are everywhere!” “Just look around this room!” He pointed out the whiteboard and the table, “and look outside, there’s even more! Practically everywhere you look!” He dragged Atkinson out for a walk, something he was fond of doing for thinking, and started pointing out all the rounded corners. After they found 17 within 3 blocks and got to a No Parking sign with rounded corners, Atkinson agreed it needed to be done.

Hertzfeld recalled, “He returned to the office that afternoon, with his demo now drawing rectangles blisteringly fast.”

His attention to detail was applied to the packaging as well, a tradition that also came to embody Apple’s brand identity. “He got the guys to redo it fifty times,” recalled Alain Rossmann, a member of the Mac team. “It was going to be thrown in the trash as soon as the consumer opened it, but he was obsessed with how it looked.”

But the Macintosh was getting further and further behind schedule. In 1982, his favourite maxim had been “Real artists don’t compromise”.

But in 1982, 279,000 Apple 2’s were shipped, compared to 240,000 IBM PC’s and it’s clones. But by 1983 it was 420,000 vs 1.3 million. IBM was pulling away.

By 1983, a sense of urgency had come over him, and thus “Real artists ship” was the maxim of the year. Once the design had been finished, only a few months before the release (with the software still being worked on until the last week of release) Jobs threw a party. Another maxim: “Real artists sign their work,” he said. He called up each member one by one, and had them sign a sheet of paper with a Sharpie. The signatures were engraved on the inside of each Macintosh. Steve signed last. “With moments like this, he got us seeing our work as art.” Atkinson fondly remembered.

The Release

Although named after a piece of fruit, Jobs was confident that his company could compete with the titan that was IBM at the time. He viewed IBM as The Empire, and himself as a Jedi Warrior or Buddhist Samurai. He strategically framed the battle as both economic and spiritual in his advertising campaigns. “If, for some reason, we make some giant mistakes and IBM wins, my personal feeling is that we are going to enter a sort of computer Dark Ages for about twenty years”. “Once IBM gains control of a market sector, they almost always stop innovation.” Looking back on the moral crusade many years later, Jobs felt the same: “IBM was essentially Microsoft at its worst. They were not a force for innovation; they were a force for evil. They were like ATT or Microsoft or Google is.”

The Macintosh was set to release in January of 1984. Jobs wanted an advertisement as revolutionary as the Macintosh. Jobs hired an advertising agency, and, working closely with them, developed a “Why 1984 won’t be like 1984” tagline. They built a 60 second storyboard around it, and got Ridley Scott, fresh off directing Blade Runner, to direct it. It would premier at the 1984 SuperBowl.

The ad was important for Jobs, because he straddled both corporate and counter cultures. He wanted others to not just see Apple as another IBM, but a rebellious, cool, and heroic company. For Jobs, this ad was a reaffirmation of everything he and Apple stood for. Apple and Jobs could stand again with the hackers and rebels, those who thought different.

Jobs screened the ad for the board in December, a month before the Macintosh was set to release. Sculley recalled that most thought it was “the worst commercial they had ever seen.” Sculley himself, happy with it before, now got cold feet. Jobs was frustrated. His intuition was telling him it was amazing, but everyone on the board disagreed. The board decided to sell off their advertising spots, but in a stroke of luck, the advertising agency decided to defy the board, and kept the 60 second slot, saying “it was impossible to sell” when it really wasn’t. Jobs would have done the same, and was thus over joyed. Bill Campbell, the head of marketing was a former football coach himself. He decided to throw the long ball: “I think we ought to go for it.”

Early in the 3rd quarter of Super Bowl XVIII, the Raiders scored a touchdown against the Redskins. But there was no instant replay. Instead, the screen went black. The commercial that would go viral for the next month, and be named both by TV Guide and Advertising Age as the greatest commercial of all time, began to play…

Jobs would then do something that he would repeat over, and over, and over. From the Macintosh to the iPad. He would intuitively find ways to dazzle, to charm, to stoke excitement, to trade exclusive access to certain journalists he knew were more prideful then others, and more than anything, he could, like a magician, create both mystery and exciting allure for his products.

And of course, the keynote speech. Jobs would spend days with no sleep in the auditorium, barely adjusting stage lighting, the presentation, or and enedlessly reheasing his speech. Everything needed to be perfect. He stayed well into the night before the unveiling, indulging in his Kubrickian perfectionism. When it finally came, it did not disappoint.

The lights dimmed as Jobs appeared onstage. He first read aloud the last 6 verses of Bob Dylan’s (his favourite artist from his teens and until he died) The Times They Are A-Changin. After that, he launched into a dramatic narrative of the history of personal computing, again pitting IBM as an Orwellian foil to Apple’s team of swashbuckling rebels. As he built to the climax, the audience, murming, then applauding, finally burst open into frenzy as Jobs, with a flair of drama, walked across the stage to a small table with a cloth bag on it. Like a magician, he suddenly unveiled the Macintosh before the audience, hooked together the keyboard, mouse, and computer, pulled a floppy disk out of his shirt pocket, inserted it, and magically, the computer began to play the theme from Chariots of Fire. Jobs held his breath for just a moment, because the demo had not worked well the night before, but this time it was flawless.

The word “MACINTOSH” appeared on screen, and then “insanely great”, as if written by someone with a pen. Then, in rapid succession, a series of vignettes: Atkinson’s quickdraw graphics package, followed by different fonts, documents, charts, drawings, a chess game, a spreadsheet, and a rendering of Steve Jobs with a thought bubble containing a Macintosh. The crowd erupted.

When it was over, Jobs smiled and said “We’ve done a lot of talking about Macintosh recently, but today, for the first time ever, I’d like to let Macintosh speak for itself.”

“Hello, I’m Macintosh. It sure is great to get out of that bag.” The little computer said in a charming robotic voice.

Pandemonium erupted. The room burst open with Beatles-esque shrieks and chanting. The ovation lasted 5 minutes.

After the event, a reporter from Popular Science asked Jobs what type of market research he had done. “Did Alexander Graham Bell do any market research before he invented the telephone?” He replied.

The Macintosh went on to become the first mass market computer with a graphical user interface and a mouse. This changed how people thought about computing, and inspired someone by the name of Bill Gates to launch his own version of a desktop style user interface, one that would start one of the most famous rivalries in technological history.

But that is a story you should learn by picking this book up. So too should you learn about how Jobs get’s booted out of Apple less then a year later, how he then revolutinizes the animation industry with Pixar, and then invented the idea of the Apple store, and then iPod, which revolutinzed how we consume music, the iTunes store, which saved the music industry, the iPhone, which brought the world into your hand, the App Store, which spawned an entirely new environment for business and creativity, the iPad, which launched tablet computing, iCloud, which let all devices sync seamlessly, and Apple itself, which, as Isaacson wrote: “Jobs considered his greatest creation, a place where imagination was nurtured, applied, and executed in ways so creative that it became the most valuable company on Earth.”

If you are skeptical of just how much of a role he played in the creation of those devices, I implore you to read the book. Apple isn’t as innovative as it used to be, so it is perhaps hard to think of it as being on the cutting edge. But from the late 90s to 2011, Apple, led by Jobs’ wondrous intuition and perfectionism, revolutionized industry after industry, and changed the way we live more fundamentally than anyone since perhaps Henry Ford.

So, Jobs goes from an arrogant asshole at the start of his life and this blog post, to an arragont asshole who can make great products people love. The former are isolated, perhaps geniuses, who will make the world slightly worse and be forgotten about. The latter are charismatic messiahs who people follow to the ends of the Earth. Steve Jobs was the latter. He could create whole new products and services that consumers did not even know they needed, not through reason, like market research, but through intuition:

"Some people say, “Give the customers what they want.” But that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I think Henry Ford once said, “If I’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me, ‘A faster horse!’” People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.”

Steve Jobs is the Randian hero, someone who, in the comparative desert of innovation that was the post 1960 period, carried forward the torch of innovation, fighting against the tide of the Great Stagnation by integrating bits and atoms like no one else could.

So the takeaway? Be more like Steve Jobs. Be more of an asshole. When a waiter serves you a terrible plate of food, complain to the chef. If you walk into a movie theater and the movie sucks, walk out. If someone tells you something and it’s shit, then say it’s shit! Our society isn’t honest enough, which is odd because we put that virtue on such a pedestal, and yet so much of our daily interactions are incredibly inefficient because only ‘crazy’ people like Steve Jobs are actually candid. If you know something is right, and no one else is saying it, don’t be afraid of being ‘unreasonable’. Say it.

Second, rely on your intuition more. Jobs wasn’t an engineer, but he had a sense of what was elegant, intuitive, and right. He cultivated that. He took calligraphy classes in school and thought about them deeply. He loved art, and explored it’s diversity in style across regions. He listened deeply to music, playing Dylan tapes over and over and trying to understand their lyrics. So to live like Jobs is to treat your taste as sacred, and build it through exposure to beautiful things.

Thirdly, you should be less conformist, and more ambitious. Jobs did LSD and smoked weed when everyone over 25 told him not to. He went to a small liberal arts college in Oregon even though he could have gone to Stanford. He then dropped out anyway. He travelled to India for months. He bet on technologies and ideas others thought were impossible. More then anything, he didn’t listen to others when he thought he was right, no matter their conviction. And he took chances when others wouldn’t have. We can all do more of that.

Last, think of reality as more malleable. This gets back to conventions. We think back at history and say, “There’s no way I can do that, because others couldn’t” or, “I couldn’t, so I can’t now.” But often, those people, or yourself, couldn’t do it because of a deficiency in will power, not the fundamental laws of physics. Jobs had no such deficiency, and thus was able to do things, and get people to do things, that they never dreamed were possible. The cure to this deficiency? Read Nietzsche Steve Jobs

And one more thing.

If anyone deserves the prize of chief architect of our daily lives in the past 100 years, it is certainly Steve Jobs.

Next time you download an app, think of Jobs. Next time you use a tablet, next time you use a paid digital music service, next time you use a touch screen, next time you look at a grid of app icons, whether on a computer or smartphone, next time you drag a file around, next time one device seamlessly syncs with another of yours, next time you watch a pixar movie, or any computer animated movie for that matter!

Hopefully this book review has inspired you, at least a little bit. That was my goal. Now go read the book. That way you won’t be inspired for a little. You’ll be inspired for the rest of your life.