A Fatal Flaw in Yarvinism

City-states are a self-defeating experiment

Alex Tabarrok recently commented on the NYT Curtis Yarvin interview. Many of you will know who Curtis Yarvin is. If you don’t, ask Grok or DeepSeek. But many might know him without actually knowing his political philosophy. I was like that for a time. But he’s become so influential in DOGE and in right-wing think tanks that I found it necessary to really understand what he’s proposing. This post is the conclusion of that research. And I’ll spoil the ending: He’s right on incentives, but he’s (surprisingly) wrong on history.

So, getting back to the interview. Alex wasn’t so impressed. Yarvin’s got two main ideas, one is on the micro level, concerned with the structure of government, and the other is macro, concerned with the structure of states. Tabarrok seems to have focused on the micro arguments, and either ignored or missed the macro ones. This is a problem, because neither makes sense without the other. Even then, I still think Yarvin is wrong, but we’ll get to that. First, Alex’s claims:

Alex quotes Yarvin as saying

“Yes. I think that having an effective government and an efficient government is better for people’s lives. When I ask people to answer that question, I ask them to look around the room and point out everything in the room that was made by a monarchy, because these things that we call companies are actually little monarchies. You’re looking around, and you see, for example, a laptop, and that laptop was made by Apple, which is a monarchy.”

Alex correctly points out that centralized organizations are not the secret sauce of capitalism. Apple doesn’t produce great products primarily because of its corporate structure, this minor determinant is swamped by the much more causal driver of creative destruction, of course. Economists know this, just like Biologists know that organisms are successful and efficient only because they are constrained and competed against by a sea of rival organisms. When one analyzes competitive markets, natural or financial or geopolitical, respect should be paid to both Darwin and Schumpeter.

But anyways, Alex goes on to criticize Yarvin further:

Markets do hold lessons about governance, but Yarvin draws the wrong conclusions. Democracy, not monarchy, is the political system most analogous to capitalism. As Mises observed, “The market is a democracy in which every penny gives a right to vote.” The analogy works both ways: voting in a democracy mirrors spending in a market. Both systems empower individuals—consumers or voters—to shape outcomes, whether by determining market success or selecting leaders.

So Alex decides no, we shouldn’t create monarchies, but instead design systems that create choice and competition, that is the real lesson to learn from the virtues of capitalism.

As much as I enjoy this critique, as I said earlier, it misses the 2nd part of Yarvin’s thought. Now Yarvin is characteristically mysterious and longwinded, and I don’t blame someone if they can’t understand what he’s really about. But here it is: Yarvin actually completely accepts Alex’s claims. He understands the benefits of competition. That’s why Alex quotes him as saying the government is like a monopoly. He’s calling the government a monopoly not just because it’s a convenient word, but because the breaking up and diversifying of the political market is a core goal of his. Yarvin references Apple products not just because they were made by monarchies but because he recognizes that while the tech market is highly competitive, with thousands of competing firms, the political market in the U.S. has exactly one firm, and thus, zero competition.

So, due to this incentive structure, you would put a high probability on the tech market becoming more efficient, serving demand better, and continually pushing the technological frontier, while the political market would become more inefficient, more self-serving, and fall further behind on innovation in public policy. And Yarvin thinks this probabilistic argument is confirmed by the evidence. I don’t think this claim is far off.

This brings us to Yarvin’s complimentary macro argument. He envisions governments subject to market competition, hundreds of polities all competing for your tax revenue. In order to attract you, governments would be incentivized to offer the most attractive models for governance. Would this be democratic? No. But instead of voting on paper, you would vote with your feet. This is similar to the voting consumers practice in a goods market, and it benefits from an obviously better incentive structure. Voters deciding where to live have clear feedback mechanisms. So, you can see that he thinks governments should be subject to market competition, where the best governance models outcompete inferior ones. Yes, they are autocratic, which Alex has disagreements with, but they will be surrounded by competing autocracies. Governments would have to provide good policies to attract and retain citizens, just as businesses compete for consumers.

Economists like Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabbarok are highly interested in Charter Cities like Prospera or the benefits of federalism for similar reasons. It makes sense that conditional on freedom of mobility, Yarvin’s incentive structure would spur greater government efficiency. So has Yarvin paid his respects to Darwin and Schumpeter? I think he has. This system does satisfy the idea of creative destruction much more than our current democracy. Our current democracy is riddled with disincentives. David Friedman wrote that political market actors almost never receive much of the cost of their actions. Similarly, voters never receive much of the benefit. Unlike non-political markets, the feedback mechanism is so weak to be almost non-existent, which is why most citizens are rationally ignorant. Similarly, the distinctive structure of government produces politicians who, instead of optimizing for efficiency, optimize for winning elections, which are of course not the same thing. One could imagine (and it is not hard to imagine) how many inefficient projects have been funded by politicians hoping to get their constituency to reelect them instead of trying to ensure long-term financial stability.

But here’s the problem. Maybe he’s paid respects to those two, but there’s a third name he’s forgetting. And yes, it’s Alexander the Great.

Hear me out now.

I love Yarvin’s ideas about government inefficiency and the benefits of competition. He’s on the money, theoretically. But practically, this is on the communist level of naive idealism. (Yes, Outrageous Fortune said it first. Yarvin is a Dark Enlightenment thinker in content but a communist in spirit.)

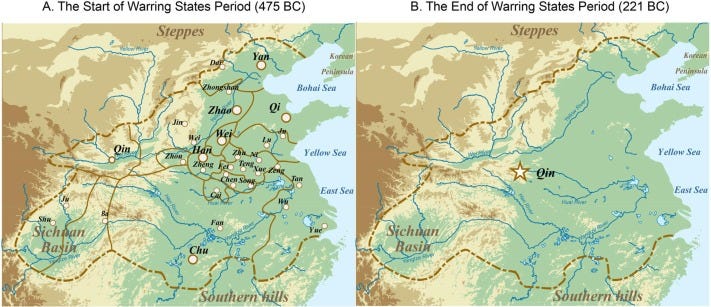

The problem is that he’s so close to being right. The benefits of competitive polities pan out in history. For example, the warring states period in ancient China (between 475 BCE to 221 BCE) directly supports Yarvin’s hypothesis! It was a moment in time with hundreds of petty polities that, over a couple of hundred years of fierce technological and strategic competition, coalesced into 4 or 5 states, and eventually, Qin Shi Huang, one of the many warlords of the time, finally succeeded in out-competing his rivals, and establishing the first monopoly Chinese Dynasty. In that period, this highly competitive state structure produced crossbows and iron weapons, birthed Confucius and all of his disciples, (such as Mencius, Yarvin’s semi-inspiration) and also the Daoists, the Legalists, and Moism. It was undeniably a huge flowering of philosophical and scientific achievements in Chinese history. In part, I contend, thanks to the competitive atmosphere from which it came.

You want more evidence for the claim? Ask yourself: “What was happening on the other side of the world, at around the very same time?” The city-state culture of the Mediterranean! (Socrates was born just a decade after Confucius died) Of course, it goes to say that the Ancient Greek city-state period was highly innovative, not just in philosophy but also in mathematics, physics, and astronomy. But while Aristotle was pontificating on city-states being the idea polity, this whole political framework was all being made quite irrelevant by his disciple, Alexander The Great. Alexander, like Qin Shi Huang, ended that competitive political market and birthed a monopolistic one. He ushered in a new incentive framework, one the Roman Empire quickly filled, which, because the incentives had changed, caused innovation and creativity to be traded off for stability and uniformity.

What does this have to do with Yarvin? My argument is that Yarvin’s idea is impracticable because, as Marx thought, technology is a causal force which shapes political and cultural history. Now historical materialism is understood by Marxists to mean that technology shapes class relations, which in turn drives political and cultural history (viewed through class struggle). G. A. Cohen reconstructs this into a stronger claim, which is that material conditions (technology, among other determinants) have a causal effect on the scale of political organization. If technological advancements favour larger, centralized states (through military or communication technologies), then breaking them into competing city-states is fighting against historical gravity. I like this reconstruction of historical materialism much more, (from now on, when I say historical materialism, I am referring to Cohen’s reconstruction) and I think its convincing power demonstrates the flaw in Yarvin’s argument.

That is, Yarvin fails to pay respect to Alexander the Great because Alexander is the quintessential example of historical materialism. He recognized that there were periods of small-state competition (Greek polis, Warring States China) that led to flourishing innovation, but that they could be consolidated into empires once technology enabled it. There’s no one in history that knows how wrong Yarvin is better then Alexander, because he dismantled with his own hands the very idea Yarvin is armchair philosophizing about.

The end of the city-state era came only after key technological and organizational advances finally aligned to support large-scale empires. Before Alexander the Great, the military and logistical capabilities required for empire-building in a region as geographically complex as the Mediterranean simply didn’t exist. But Alexander’s use of Macedonian phalanxes, siege technology, and naval power, enabled him to deploy large, professional armies to conquer much of the Greek world. Alexander had to have supply chains running through India and Persia and the Balkans and up and down rivers connecting to ports and more ports. And then from those ports how far a horse could travel. And how much weight could it carry? Even through a desert with no food or water, how much of the weight could be non-food and water? His skills as a military tactician are properly rated, but what’s truly underrated was his ability to not only conquer but subdue these polities. The more you learn about him, the more his mastery over logistics will amaze you. His innovations in this domain are really what stuck the knife in the city-state period. I would also add that a factor unrelated to Alexander was the spread and retention of Hellenistic culture, across vast land and sea, which was only made possible by more sophisticated communication technology. This was instrumental in creating the infrastructure necessary for a unified empire.

So here’s what I’d say to Yarvin: Look, I love that you understand the benefits of creative destruction, we can see that in the ecosystem, we can see that in goods markets, we even see it pan out historically in the warring states and Greek city-states period. But there’s a reason those periods roughly ended concurrently. Because once technology gets to a point where rulers can effectively hold on to empires, city-states become irrelevant because they can’t compete against the returns to scale that empires enjoy. So, if you were to magically turn the U.S. into 500 small polities, would you would see a flowering of technological and cultural innovation? Highly likely. But within 100 years, the most efficient polity would have conquered all the others, and we would soon be back at the same place, perhaps a worse place. It is technologically unavoidable. The only way to prevent it would be to set us back to an ancient Greek technological and political model, but of course, this competitive model would spur innovation (some of which in communication and logistics) and thus allow for empires, just as it did before.

So city-states are actually self-destructive. They supercharge innovation, which has an unintended side effect of making governments more efficient at coordination and resource management. Once a certain threshold is reached, the innovation which city-states fostered inevitably pushes their political framework out of business. So making diverse polities where voters can choose their government is a temporary and self-defeating experiment. The only reason goods markets work indefinitely is because, although the returns to scale are high, we have anti-trust laws. But there will be no world government to enforce Yarvin’s idealistic ideas.

But Singapore! The reader might say. Isn’t Singapore an exception? Yarvin is fond of using Singapore as an example too. But Singapore is the exception of all exceptions. First of all, Singapore happens to exist on the most important trade route in the world. The wealth and infrastructure of Singapore are built on its position as a global financial hub, which relies on its key location in global trade markets. It was also created as a political fluke. It was supposed to be a part of Malaysia after the British left, it was situated in an obviously enviable global position, there was a reason its fall in 1942 was one of the most important moments in the Pacific War. But in one of the worst decisions in history, Malaysia expelled it in 1965 due to ethnic divisions, as the Malaysian government did not want to share power with the predominantly Chinese population of Singapore. The reason this is a fluke is because, as I have written, history shows that leaders are incentivized to take resources, not expel them. Expelling Singapore was an exception to this 4,000-year rule. Thus, I don’t find Singapore to be a compelling, generalizable counterexample. Its existence is unlikely to be replicated. And its military safety is only assured because Singapore finds itself to be in a unique time in which large states uncharacteristically find it optimal to enforce a norm of non-aggression. I find it unlikely this would stay in place if, the U.S. for example, decomposed into 500 city-states.

So Yarvin’s got it half-right and half-wrong. Competition is great, but it only works in semi-regulated systems like goods markets, where the rule of law demarcates the do’s and don'ts, and in this little bubble of artificially created competition, great things can happen. The lesson here is the importance of incentives. Let firms compete with minimal interference, and you’ll get the automobile and the internet. But remember that without government, competition over intellectual property would quickly turn into a might-makes-right incentive structure. And the end of that tunnel is the Roman Empire, not the singularity.

Evil article. City states give you cool bonuses. +5 Science W. This guy sucks.

Terrible article, haven't read it yet. Also the author sniffs glue.